Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

The small theater is achingly silent after Niya Kenny’s desperate shouts echo across the room.

Nobody’s gonna help her? You did this! You didn’t even have to call the administrator!

Projected on the back wall, footage of a 2015 incident Kenny witnessed at Spring Valley High School in Columbia, South Carolina plays: It shows a school resource officer violently throwing her classmate, the then-16-year-old student known only as Shakara, from her desk, then dragging her across the room.

Lights dim and Kenny fades back into darkness.

In the audience, students from Alcott College Prep High School in Roscoe Village are still and rapt. The restless energy and teenage snickering they’ve exhibited at other moments during the two-and-a-half-hour play suddenly quieted.

Kenny and Shakara’s story – portrayed by actors Adhana Reid and Mildred Marie Langford in a scene from TimeLine Theatre’s production of “Notes From the Field” by Anna Deavere Smith – struck close to home.

“Notes from the Field,” centered around police violence and the school-to-prison pipeline, is a particularly relevant subject for Chicago students right now. Chicago Public Schools are on the precipice of major change after the Chicago Board of Education voted last week to remove police officers from schools by the start of next school year.

“Notes from the Field,” which runs through March 24 at TimeLine Theatre in Chicago’s Lakeview East neighborhood, examines the school-to-prison pipeline in the U.S. through a series of monologues with various people affected by and working to combat it. It was drawn from over 250 interviews Deavere conducted on the subject, including with well-known figures such as the late civil rights leader and U.S, Rep. John Lewis.

This particular matinee on Feb. 14 was a special performance just for students at Alcott College Prep as part of TimeLine Theatre’s Living History Education program.

The program sends theater artists into CPS classrooms and brings students to the theater to engage them in productions steeped in history and current events that touch their lives.

The play’s themes – discriminatory policing and violent encounters with police – are all too familiar for Alcott students and faculty, who say they still occur in students’ communities outside of school.

In the 19th police district where Alcott is located, Black residents made up 54% of the subjects of police use of force incidents since 2019, according to the CPD Use of Force Dashboard. Citywide that percentage is 74.48%, while Black residents are about 28.8% of the Chicago population, according to 2022 U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

As Alcott junior Leo Sepulveda said in a post-show discussion at his school, “It still goes on. On your own time, out in the neighborhood.”

And as some Alcott students learned from “Notes from the Field,” such experiences can affect students’ futures whether they happen in school or in their communities.

Connecting theater to the classroom, students’ lives

Seeing the play is only one part of the Living History program. Before the students are ready to watch the story unfold on stage, they spend six to 13 sessions working with Living History teaching artists – learning more about the play and the social context around it and even acting out scenes from the play.

Then they attend a special matinee at the theater, followed by a debrief with the actors back in their classrooms the next day.

With a play like “Notes,” dealing with something so close to the students’ experiences, the teaching artists make sure to help students process the subject matter and express their feelings about it.

“It allows you to sit in a space and note that it is not your fault. It is the fault of the system failing people,’ said Living History teaching artist Marcus D. Moore. “It takes that burden off of them, because they are carrying already so much in the world.”

Alcott students understand violence at the hands of police officers “because they live it in their neighborhoods,” said Beth Pfeiffer, Sepulveda’s teacher at Alcott who coordinated the workshops with TimeLine.

And across Chicago, some students live it at school.

Although the number of calls to police in CPS have decreased in the past decade, police are still called on Black students in schools at a disproportionate rate, despite the fact that Black students do not commit crimes at a higher rate. In the 2022-23 school year, 68% of the more than 1,300 CPS students who received police notifications were Black, according to district data.

Black students also still make up a disproportionate number of in-school arrests, which have decreased overall by approximately 80% districtwide between 2012 and 2019, according to an August 2020 press release from CPS.

That is part of why Pfeiffer, who has coordinated with TimeLine’s Living History program for 15 years, decided the 80 students in her three English and general education classes needed to see “Notes from the Field.”

So, the first week of February, TimeLine teaching artists came to Alcott and took over Pfeiffer’s classes. Students did breathing and movement exercises, studied some of the monologues from “Notes,” and drew connections between the play and their own lives.

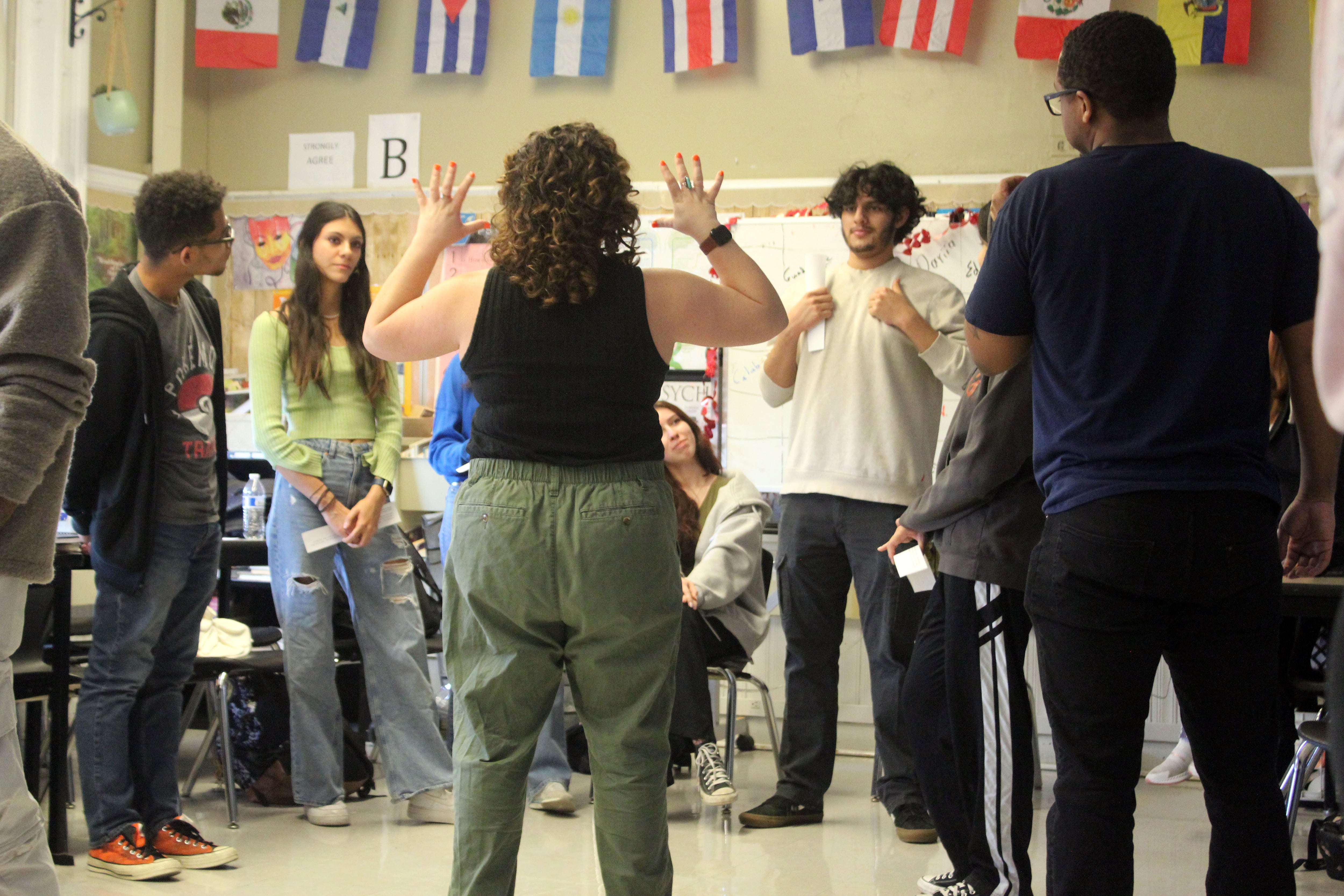

On day three of the six-session “residency,” as TimeLine calls it, the students stood in a tight misshapen circle crowded by the desks that had been pushed against the walls. Three teaching artists led them through an acting exercise in which they had to try to physically embody some of the characters from the play.

As they went around the room, most of the students were uncomfortable and shyly shrugged or fidgeted with the slips of paper with their monologues on them.

When they split into groups to practice stepping into their characters’ shoes and recite their lines, things livened up. Junior Felipe D. laughed as he lounged on a table, stood on a chair, and tried out increasingly unlikely postures to embody former NAACP Legal Defense President Sherrilyn Ifill.

When teaching artist and TimeLine company member Charles Andrew Gardner approached, he didn’t shut down the students’ antics. Instead he rolled with it, encouraging them to examine why they chose those postures.

“It’s very student-led,” he said after the class. “Like, what environment would you all work in best to do your best work? And then we just match that energy.”

A cluster of young women across the room giggled through their lines but also tried out gestures of support to portray their characters such as holding hands.

Nearby, another group was deadly serious as they rehearsed at a makeshift podium.

The students’ different approaches were welcomed by the three facilitators who floated around the room offering tips and adapting to each group’s different vibe.

It is, after all, uncomfortable work trying to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, said Gardner.

“One of the main transferable skills of theater is empathy,” he said. “It’s literally ‘how can I look at this script and try to understand this person who they may not share anything with?’”

But it’s not just about empathy for the characters, it’s about empathy for themselves and each other too, he said.

“I think that that’s the arts job to say, ‘We’re listening. So express yourself,’” he said

The Alcott students began their dive into “Notes” just a couple of weeks after four students in Chicago were shot and killed outside their schools. The shootings didn’t come up specifically during the residency, but Pfeiffer said students have brought it up separately in class.

“We’re fools if we don’t think that they’re absorbing what’s going on,” said teaching artist Lexi Saunders.

‘They see it in their own lives’

Pfeiffer doesn’t shy away from difficult subjects. In 2018, for example, she signed her AP Psychology students up for a residency with TimeLine built around a play called “Boy,” which took on topics such as gender identity and surgical transition.

Aside from programming with TimeLine, she has also introduced her students to Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery, Alabama-based nonprofit that offers legal representation to wrongly-convicted prisoners, and she’s brought police officers into the classroom to shed light on their experiences.

“I like to take more risks than other teachers,” she said. “Sometimes I don’t think they are ready. But I want to get myself ready and get them ready, so they can get as much out of it as they can. And if you wait, we may never be ready.”

When she signed her students up for “Notes,” she knew a two-and-a-half hour play full of monologues would be a challenge for restless high schoolers.

But the 11th graders in her classes have grown up amid high-profile police brutality cases, school shootings, nationwide protests for racial justice, and, of course, a pandemic.

“I think when they get it, they get it all too well, and they see it in their own lives,” said Pfeiffer.

When the house lights came back on after the matinee performance on Valentine’s Day and the play ended, one of TimeLine’s Living History teaching artists posed a question to the crowd of students: “What stood out to you?”

Without a beat, the first answer was shouted from the audience: “The girl who was thrown across the room.”

In written post-show reactions the next day, they reflected powerful insights and emotional connections to the play.

“The childhood a child has and the treatment they receive really affects them in their adulthood. It’s a full cycle that continues to happen,” wrote 11th grader Julia R.

Felipe D. wrote that he was particularly moved by the scene with Niya Kenny and Shakara.

“It seemed so deep and still sticks to my head,” he wrote.

“My takeaway was the theme of hate coming from police, not racism, but hate. That was a quote I remember. In almost each scene it was either about hate or the reaction to hate,” wrote Ismail C.

Two days after the Alcott students saw the play, two “Notes” actors visited Pfeiffer’s classes to debrief with the students and answer questions.

During the discussion, student Sammy C. noted how the play reminded her of Laquan McDonald, the 17-year-old Chicago high school student who was shot 16 times in the back by a Chicago police officer in 2014. She learned about McDonald last year when the class read “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas and then researched police brutality cases and shared what they learned with their peers.

These reflections demonstrate everything the teaching artists and Pfeiffer hoped the students would get out of the experience – empathy, emotional resonance, and greater understanding of the school-to-prison pipeline.

It’s Pfeiffer’s plan to take it a step further and turn those reactions into action.

“It’s very frustrating if you don’t focus on any glimmers of hope,” she said.

The energy from the students crackled to life when actor Shariba Rivers let some of her anger and raw emotion break through as she talked about the scene of the play that moved her most – Kevin Moore’s monologue about filming the brutal 2015 beating of Freddie Gray, a Baltimore man who died of a severe spinal cord injury sustained while in police custody.

Rivers, who spent almost 30 years as an educator in Chicago and is now an instructional coach on the South Side, recited his lines: “‘Can you crush your own larynx? Can you sever your own spine? Can you do this to yourself?’”

“The first time I heard the story that way, I was gutted,” Rivers said, before settling into a calm anger.

“He did not deserve to be treated like that,” she said. Nods and mumbles of agreement arced around the classroom. “He still deserved a day in court, he needed to show up alive. It doesn’t matter if you’re doing something wrong. You still should be allowed to show up alive in court.”

The school bell rang, cutting her off mid-thought. But the students paused their usual rush of packing up — and gave Rivers hearty applause.

Correction: A previous version of this story misidentified Living History teaching artist Marcus D. Moore.