Editor’s note: This story was produced by the IndyStar. Please do not republish without their permission.

Maya Dennis is excited. She just mastered writing a lowercase letter “f” and she knows it.

“I’m doing a great job!” the kindergartner shouts excitedly to no one in particular, though her tablemates crane their necks to see how Maya has neatly traced the letter between the dashed lines of her worksheet.

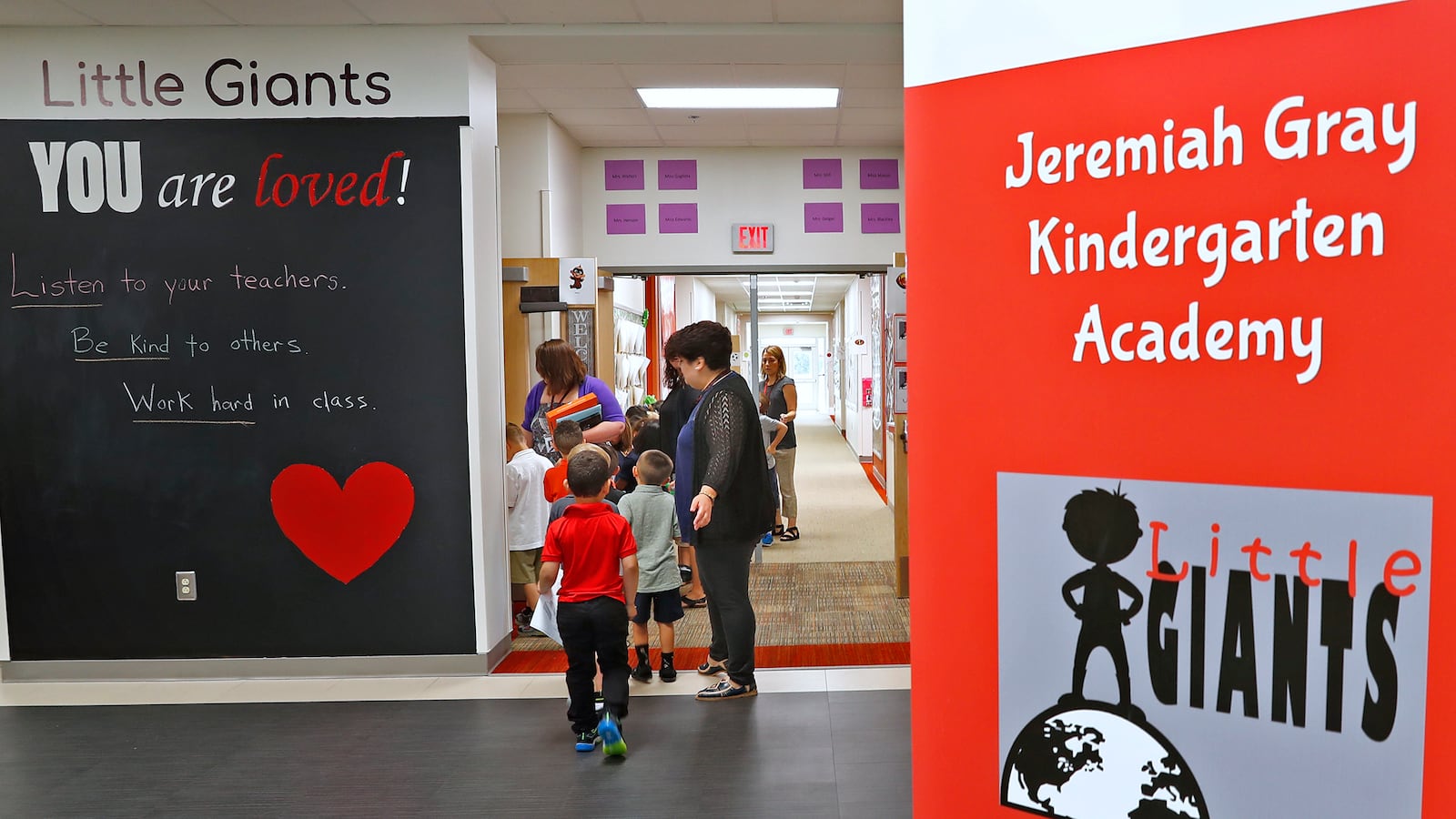

Their teacher at Jeremiah Gray Kindergarten Academy, Brooke Gagliola, is at the front of the classroom repeating the steps onto her own worksheet, projected onto a large screen for those students who haven’t quite mastered it like Maya yet.

It’s the eighth day of kindergarten for the 1,400 or so 5-year-olds in Perry Township Schools and for many of them this is their very first formal school experience.

And it’s an important one. They won’t just learn their letters in Miss Gagliola’s class. Kindergarten is often where little kids learn how to “do” school – how to interact with each other, follow directions and pay attention for prolonged periods of time. Increasingly, it’s also where kids learn foundational academic skills in reading, writing and math that will serve as the building blocks for their next 12 years of school.

“I’ve got 5-year-olds talking about a rhombus and a trapezoid or adding numbers already,” said Lora Hansell, kindergarten principal at Jeremiah Gray. “They are learning some pretty meaty things, things that we did not learn until first or second grade.”

But for all of its importance, kindergarten is still not required in Indiana. It’s one of 33 such states, according to the Education Commission of the States, which tracks legislation and policies nationwide.

The state fully funds kindergarten, so nearly all kids go. But Vickie Carpenter said they still see a few kids each year that start school without that critical experience. That puts them behind, she said.

“Kids that don’t go to kindergarten are at a big disadvantage for first grade,” said Carpenter, assistant superintendent for elementary schools in Perry Township. “It’s not like it was before. They don’t just play. They play with a purpose.

“Everything is intentional, and it’s around what kids need to learn socially, emotionally or academically.”

So, why doesn’t Indiana require it?

Some say it’s unnecessary since the vast majority of kids already go to kindergarten.

Indiana requires school districts to offer kindergarten and the state fully-funds full-day kindergarten classes, though schools are only required to offer half-day programs. In short, the argument is all families have access to a kindergarten program and those that want to send their kids to kindergarten are already doing so.

There’s no real reason to require it says Rep. Bob Behning.

“The data says 97% of kids are participating in kindergarten already,” said Behning, an Indianapolis Republican who chairs the House education committee.

“It’s not like there’s this huge gap,” Behning said. “I’d assume some of those are parents who would prefer to have the option to have their kids still at home rather than in an institution.”

And in Indiana, where parental choice is of paramount value in education policy, many lawmakers agree they should have that right.

But there are two factors driving some policymakers to take a different position.

One is the increasingly rigorous academic expectations for students.

According to Indiana’s academic standards, by the end of kindergarten, students are expected to be able to recognize and read basic words such as “a” and “my” and count to at least 100 by ones and tens.

They start writing basic sentences. They learn how to give, restate and follow simple two-step directions.

Now, imagine starting school in the first grade, not having had a formal schooling experience and entering a classroom with 25 other kids who have already built all of those skills.

Perry Township sees this year as so critical, the district built four kindergarten academies. Opened three years ago as a creative solution to overcrowding at its elementary schools, the academies were custom-built to 5-year-olds’ learning needs.

“Kindergarten is a really structured day,” Hansell said. “On the bus, we have kids fall asleep because the day is long, but they love it.

“Our kids bounce in here ready to go, ready to learn.”

Her kids will start the day with a morning meeting, where they may meet on their alphabet carpet. Each letter is in a square, which makes it easier for squirming 5-year-olds to find a seat.

Each day consists of academic blocks for reading, writing, math and specials, like music, art, PE, keyboarding and library time. And they get time to go outside and play so they can “climb, and run and spin,” Hansell said.

The idea of entering school behind is the other reason policymakers are looking for ways to get kids into school earlier. Achievement gaps are easier to close if they’re caught early and not allowed to widen over time.

This idea is what’s behind Indiana’s slow push into a state-funded pre-kindergarten program. On My Way Pre-K grants are available to low-income families, where kids tend to be at-risk for entering school behind their peers. The philosophy is that giving those kids and families access to a high-quality pre-kindergarten experience can put them on equal footing with their more affluent peers.

Kids who receive On My Way Pre-K funding are required to then enroll in kindergarten, but it’s still a tiny program, reaching only a fraction of potentially eligible families.

State Superintendent Jennifer McCormick is afraid some of the most at-risk kids are the ones being left behind in states that don’t require kindergarten.

She has made getting more children into school at an earlier age a priority during the past two years of her administration, backing bills that would lower the state’s compulsory school age from 7 years old to 5 years old.

It’s a slightly different mechanism than requiring kindergarten, McCormick said, but would have the same effect.

In most states, the age at which students are required to start attending school is 6 years old, according to the Education Commission of the States, though in nine states and the District of Columbia it’s age 5.

In 13 states, including Indiana, the compulsory school age is 7 years old. In two states, it’s 8 years old.

McCormick has advocated for Indiana to lower the compulsory school age and several lawmakers have filed bills to do just that. Those efforts have had little traction at the Statehouse, though.

“You still have a facet of Indiana lawmakers who believe it’s best to keep the kids at home in that family environment and let those needs be the responsibility of home,” McCormick said. “What our team has tried to convey is that home looks very different across the state of Indiana.”

Some families will send their kids socially well-developed and ready for school, she said.

“I’m worried about those families who make the choice to keep their kids at home and don’t have the means or resources to provide some of the experiences that are necessary for that readiness piece,” she said.

There could be any number of reasons she said, whether it’s due to challenges with poverty, mobility, homelessness or kids coming from the foster care system.

“The reality is that we have kids who come into kindergarten or first grade classrooms that don’t even know how to hold a book,” McCormick said. “They haven’t been exposed to print. Sometimes they’re not potty trained.”

The sooner those kids can get into a high-quality educational setting, the better, she said.

McCormick said her team will continue to advocate for a variety of strategies to strengthen Indiana’s early childhood education landscape. Mandatory kindergarten is still on the wish list.

MOVING 4WARD is a collaborative reporting project by IndyStar and Chalkbeat Indiana. The project examines the current state of Early Childhood Education in Indiana with an emphasis on how best to prepare our state’s 4-year-olds (hence the project title) for kindergarten and beyond. Expect stories to take a critical look at preschool programs, issues of access to those programs, the debate over the value of taxpayer-funded universal preschool, what lessons can be learned from other states, and – perhaps most importantly – what you, as a parent, need to know to make informed decisions about choosing your child’s preschool.