It had been two weeks since Terri Anderson, a teacher at The Oaks Academy in Indianapolis, had seen her 19 prekindergarten students in person. But on a recent Friday, they met virtually for the first time on Google Hangouts. The result: a cacophony of 4- and 5-year-olds on unmuted microphones.

“It was the best sound I had heard since all this had happened,” she said.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has upended the educational system nationwide, even preschool has gone online. But school closures threaten to undo some of the progress that Indiana has made toward improving pre-K access for low-income families to help bridge critical early learning gaps.

Many pre-K classrooms have temporarily closed alongside K-12 schools to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Meanwhile, demand has waned at some Indiana child care centers as more families are keeping their children home. The loss of pre-K classrooms has consequences: First, education advocates fear that school closures will worsen the disparities for students across all grades who don’t have access to technology and whose families have fewer resources to support learning at home. Second, families could find themselves without child care as they continue to work during the pandemic in roles such as health care workers, grocery store clerks, delivery drivers, and custodians.

“One of the most important things children learn in a pre-K classroom is how to do school, how to behave with other children, how to self-regulate and be ready to learn,” said Maureen Weber, president and CEO of Early Learning Indiana, a nonprofit that provides and advocates for early education. “That’s one of the things that’s going to be harder for families to achieve independently.”

Because Indiana families have a lot of choices for where to go for preschool — districts, private schools, centers, homes, child care ministries — providers are tackling the challenge in different ways, both online and off-line.

At The Oaks, Anderson wanted the recent video meeting to be a joyful reunion for her pre-K class. She incorporated pieces of their daily routine, such as taking attendance with popsicle sticks that each had a student’s name. When she drew a student’s popsicle stick, she asked them to show the class a toy or something they had made at home, giving each a turn to speak “on the big screen.”

Anderson had them all hug their computers and give themselves hugs, too, wrapping their arms around their own shoulders.

“They need to be nurtured,” Anderson said. “They need a touch. They need a hug.”

Anderson acknowledged that parent engagement is key to children continuing to learn at home — something The Oaks, a private Christian school that enrolls students from a wide range of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, regularly emphasizes.

Moving pre-K classrooms into the home also means teachers are supporting parents so they don’t feel stressed about their children “losing ground,” Anderson said. Teachers and instructional assistants regularly check in with individual students and families. The Oaks gives preschoolers 1-2 hours of learning each day, and more important than completing the work is instilling a sense of normalcy, she added. A lot of the key lessons are simple: Listen, follow directions, pay attention.

At first, parent Kelly McGary was worried when her son Sam’s preschool, Cooperative Play Academy on the city’s southside, closed its doors in early March. Sam had just learned to hold a pencil properly.

But now she’s less concerned after watching him video conference with his preschool class twice a week, and do engaging homework assignments, such as nature walks.

“I just have to put it in perspective. He’s 3½, he’ll be fine,” said McGary, a public health nurse. “Even if it lasts a few more months, we’re still interacting with him and providing for him. He has a safe place to play. I think he just misses his friends.”

At the Edna Martin Christian Center in Martindale-Brightwood, the approach to at-home learning has evolved over the last few weeks since the child care ministry temporarily closed its doors, said Alexandra Hall, director of early childhood education.

Teachers started by sending food home with students on the first day. Then, they started sharing learning resources. They gave students kits filled with art supplies, reusable writing worksheets, stories, and bubbles. Later, they decided they wanted to find a way to stay in touch with students in a dynamic, interactive way.

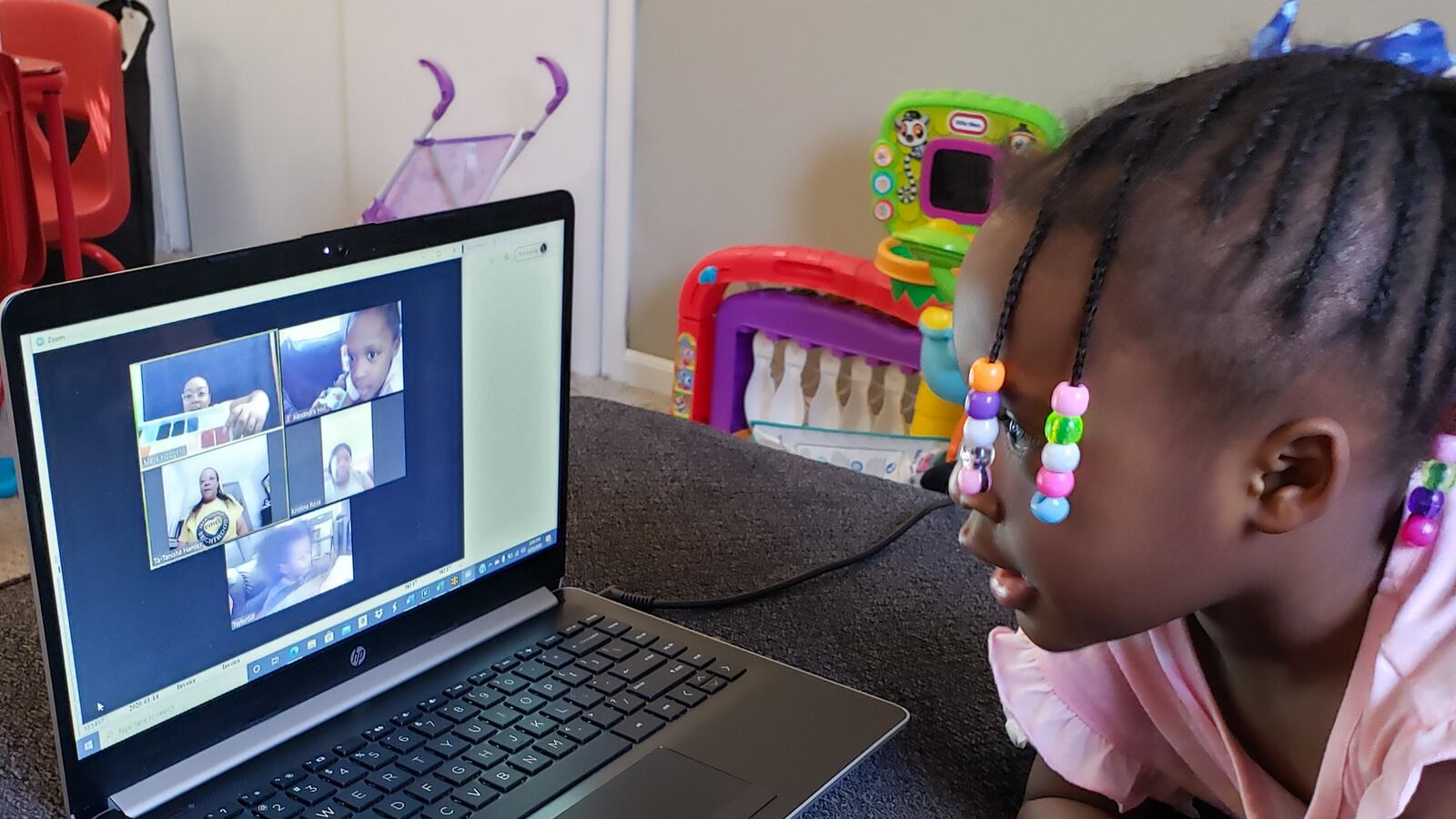

That’s how they started a series of 30-minute Zoom sessions throughout the day, mimicking a regular school routine.

“We figured if it works for adults, why wouldn’t it work with kids?” Hall said.

They hold virtual circle time and snack time. Families all gather for the video call with a healthy snack to show and share.

“That is what has just truly been a godsend during this time — to be able to look at people, even though you can’t touch them,” Hall said.

The online setting still allows teachers to be responsive to students. Just like in the classroom, “sometimes you have to throw your plan out the window,” Hall said — like when a student joined the video call in a superhero costume, prompting a show-and-tell that overshadowed the scheduled science lesson.

Even when e-learning isn’t as accessible, pre-K classrooms are finding ways to keep learning. For the five Indianapolis sites of St. Mary’s Child Center, where 93% of children come from low-income families, administrators are mostly focused on basic needs, such as directing families toward food resources.

Teachers are posting videos where they read stories, sing songs, or go on scavenger hunts. They’re encouraging families to find “teachable moments” but aren’t stressing academics.

“Children are such natural learners,” said Diane Pike, director of outreach and professional development. “If they are allowed to explore and communicate and ask questions and have that support at home, they’re going to be OK for kindergarten.”