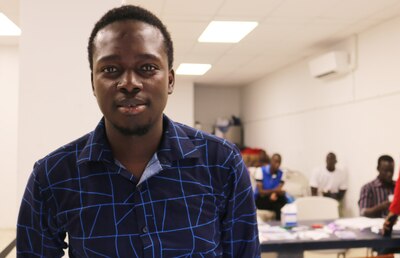

Since coming to the U.S. from Guinea four months ago, 18-year-old Sadio Diallo splits his time between school and volunteering at a community center in Harlem called Afrikana.

The center opened a year ago to help asylum seekers and is run almost entirely by volunteers who are themselves asylum seekers.

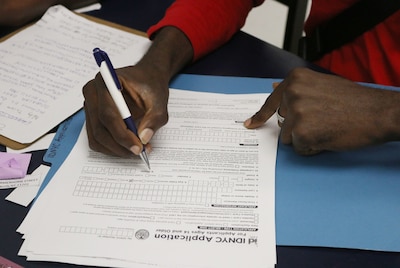

Many of them are students like Diallo, who is studying for a GED diploma. He spends his days at the center translating for recently arrived African migrants who speak Arabic, Wolof, and Pulaar, taking each asylum seeker through every page of their SNAP application for food benefits and assisting them through the process.

Diallo isn’t volunteering at the center because of Mayor Eric Adams’s recent call for New Yorkers to step up and pitch in when it comes to supporting the migrant crisis. He’s doing it because he feels compelled to do so.

“I come here because the asylum seekers need my help,” Diallo said. But like the city, which is straining to support asylum seekers, Afrikana is also grappling with overwhelming needs.

“We’ve been able to keep our doors open through prayer, but we need more help,” said Adama Bah, the center’s founder.

She is now hoping to get other civic-minded high school and college students in the area to consider volunteering.

Nearly 100,000 newly arrived asylum seekers have arrived since the spring of 2022, and an estimated 18,000 newly arrived students have enrolled in the city’s public schools since then, according to city officials. Adams said he’s expecting an uptick in the number of families with children to arrive before school starts next month.

Some days, as many as 300 asylum seekers have come through Afrikana’s doors, said Bah. The center has become a hub in the community, with asylum seekers helping each other. She connects them with others in the area when they don’t know the answers.

When Spanish-speaking families, for instance, don’t understand how to navigate the Education Department’s Family Welcome Centers, where they must go to enroll their children in school, Bah sends them to Rosa Diaz, an East Harlem parent leader. When Diaz comes across families struggling with housing or food insecurity, she sends them to Afrikana.

“This has all been incredibly difficult for asylum-seeking families, and Afrikana is alleviating those challenges,” Diaz said. “When a family goes to Afrikana, I know they will not be turned away.”

Migrants get social services support and more at Afrikana

The center operates from a small run-down space near the corner of 145th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard, stuffed between two larger storefronts. There is no signage and no description of the building’s purpose. Inside, migrants sit in a makeshift waiting area spread among a group of donated and mismatched chairs.

Afrikana is open five days a week from 10:00 a.m. until 4:00 p.m., according to fliers wheat-pasted around the neighborhood. However, migrants line up outside the center as early as 6:00 a.m. Bah said that she and her staff are lucky if they leave before 7 p.m. most days. They have no appointment system unlike most nonprofits and government agencies, and this means they can never anticipate how many migrants will show up.

At Afrikana, migrants can expect to receive medical attention, shelter information, and help accessing citywide social services. There is also a daily prayer led by Imam Omar Niass, who frequently visits Afrikana to volunteer and is known for housing hundreds of migrants in the last two years in his mosque. On Fridays, a food pantry is set up for migrants and other Harlem residents. However, most migrants come to have their SNAP benefit applications completed.

Before the application can begin, migrants must have an email address and create a Human Resources Administration, or HRA, account. Then it’s a three-step process: filling out the nearly 20-page written portion, scheduling an appointment for a phone interview, and then going to a Benefits Access Center to submit the required documentation. The process is completed over weeks.

Until recently, Bah’s main focus has been Venezuelan migrants coming to New York City via Port Authority, but with more asylum seekers from African countries entering New York City, the demographics of people needing help have shifted from Latinos to Black migrants. In her 18 years of experience doing this kind of work, Bah said she’s seen Black migrants being treated differently.

“They are constantly rejected from social services, they are turned away from shelters. One shelter didn’t have a functioning shower or air conditioning for these migrants for over a week,” said Bah. Because of this, Bah spends a large amount of time going back and forth with government agencies advocating for the same African migrants, sometimes for days, rather than assisting new migrants every day.

Diallo refers to Bah as “sister” and says that she is the reason he is in school. She’s also a driving force behind his volunteer work there.

“She has done a great deal for me, and here at Afrikana she is doing a great deal for others,” said Diallo, who dreams of going to college after he gets his GED diploma.

Bah first came into the spotlight in 2005, when she was the protagonist of a harrowing documentary that told the story of her arrest by the FBI, who falsely accused her of being a potential suicide bomber and “imminent threat to the United States.” Bah went on to write about how her father’s forced deportation back to Guinea affected her livelihood. Now Bah’s focus is on keeping Afrikana running.

Bah understands the pressure of staying in school while trying to seek asylum, but she also knows how important it is for migrants to pursue their education. After last week’s document drop-off at the HRA office, Bah took the 14 migrants with her to Manhattan’s Education Opportunity Center off of 125th street in Harlem. This center offers free programs for people to learn English, get their GED diploma, and prepare for college.

Bah personally escorted them to the center because of concerns about how migrants are treated there. Even after she walked with them, many later told her they left without enrolling in education classes, turned away without support or instruction on what to do.

The Education Opportunity Center did not immediately respond for comment.

Bah receives anybody who is interested in volunteering, but she says her most consistent volunteers, whom she refers to as her staff, are made up of asylum seekers also navigating the New York City shelter system.

“They’re desperate to keep busy and help people. I tell them if they want to help others, they must help themselves,” Bah said.

Eliana Perozo is a reporting intern at Chalkbeat New York. You can reach her at eperozo@chalkbeat.org.