This story is featured in Chalkbeat’s 2024 Philadelphia Early Childhood Education Guide on efforts to improve outcomes for the city’s youngest learners. Throughout the 2024-25 school year, Chalkbeat Philadelphia is following a new teacher, Kahn-Tineta Smith, as she adapts to the joys and challenges of working in the city school district. This is the second of several periodic check-ins we hope will shine a light on the state of the Philadelphia teaching workforce. Read the first entry here.

It was barely 9 a.m., and Kahn-Tineta Smith already had a lot to deal with. One little girl was spinning around like a whirling dervish. Another had wet herself. A few others couldn’t resist the temptation to toss some of their Cheerios — breakfast is served every day in class first thing — onto the floor.

“Your [uneaten] cereal goes into the bucket,” she admonished, gently.

Through all the controlled chaos, Smith, a former paraprofessional who this year fulfilled her dream of becoming a fully credentialed preschool teacher, was unfazed. There are 19 kids ages 3 to 5 in her class at the Mary McLeod Bethune Elementary School in North Philadelphia. This is what they do.

Those are some of the everyday obstacles Smith faces. But overall, Smith had made a smooth adjustment to leading a classroom. For most of her career in the Philadelphia district, she worked as a paraprofessional at Bartram High School. This year, after raising three children, she finally fulfilled her lifelong dream to teach and got her certification from Cheyney University through a program that supports district paraprofessionals who want to become teachers and aims to help address the city’s teacher shortage.

One big difference between being an aide and a teacher is that she feels she has more authority. As a teacher, she can suggest names of families who could use food baskets during the holidays, or children who might need a winter coat, and people listen.

“I love that, to be able to advocate for families and children,” she said. “I remember when I was coming up, my teachers and counselors were advocates for me.”

She attended city schools, first in her West Philadelphia neighborhood and then in the Far Northeast, where she was bused as part of the district’s voluntary desegregation program. She graduated from George Washington High in 1991.

When she was working with high school students as a paraprofessional, Smith said, “I thought that was my calling. But now that I am working in pre-K, I feel the little ones are my calling.”

Teacher adjusts to small-group instruction, stays calm

In her classroom, Smith keeps a calm demeanor. “I go day by day,” she said. But she still faces serious challenges. She’s negotiated a steep learning curve meeting children’s very different needs. Student turnover is also an issue.

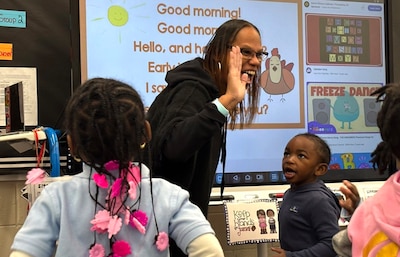

On a recent Monday morning, 14 children were in her classroom. Big, brightly colored letters adorned the walls and half a dozen play stations — from computers to an old-fashioned sandbox, from Play-Doh to building blocks — beckon. After finishing their breakfasts, many of the children ran forward for their hugs from Smith and her classroom assistant, Anita Parker. (A few even threw their arms around the new person in the room: a reporter.)

Then they took their spots on the rug to watch a phonics video in which actors sing letter sounds. They joined in enthusiastically as each letter flashed on the smartboard.

By turns exuberant, timidly curious, seriously listening, and bawling their eyes out, the children clamored for attention from Smith and Parker, who has been working in early childhood classrooms since 2002.

The kids’ behavior and attentiveness vary widely. Some of the older students are in their second year of preschool, some are brand new. Two of her students are virtually nonverbal, others are chatterboxes.

Smith has become adept at prodding students who aren’t making much sense to think harder, while offering lavish praise to those who offer a sage observation. “I love that!” is one of her favorite expressions.

In her first days leading the classroom, Smith worried about mastering the curriculum: its focus areas, question of the day, and detailed instructions on how to conduct small and large group activities.

No worries there. Now she has it down, although she’s modest about it. Asked about any continuing challenges, she said she is “still getting used to small group instruction.” Because the children are at such different developmental levels, she tries to group them sensibly, but she also wants to give them choices.

“While we’re focusing on one group, we have to keep an eye on what the other kids are doing,” she said.

Which kids are around to keep an eye on has fluctuated. Since the beginning of the school year, some students left while others enrolled. One joined just last week. A few might need special education services, but so far, only one has been evaluated for a possible one-to-one aide. She is hoping that person will start by January.

“It takes a long time for them to get support,” she said.

“How I deal with it, I go day-by-day.”

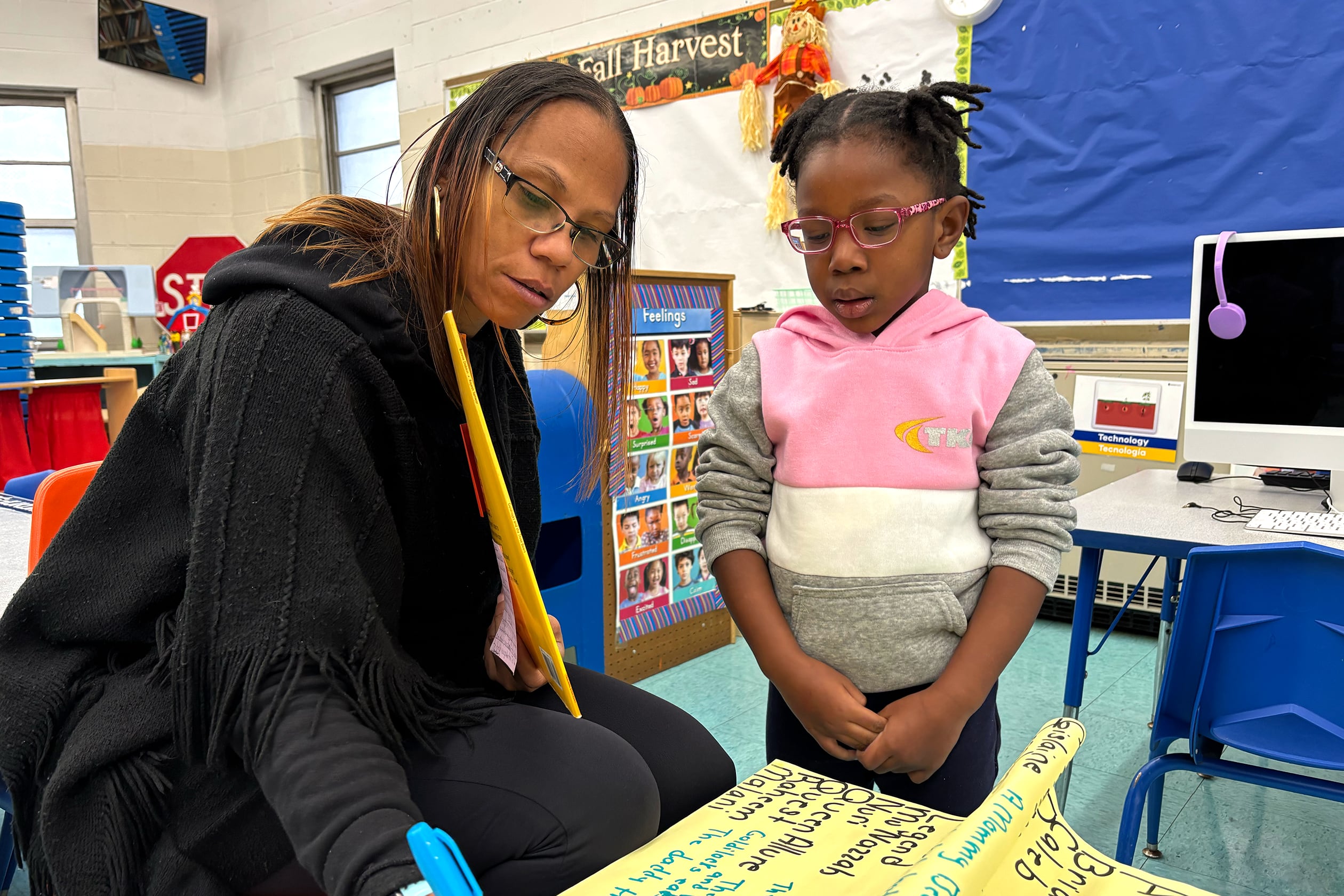

By 9:15, Smith was sitting at a tiny desk with a long sheet of paper as students paraded by her one by one to answer the question of the day: “What do you know about the story ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears?’”

Many students hadn’t yet heard the full story, at least not in class. But they had been able to leaf through the book and look at the pictures, and the point of the exercise was for them to use their imaginations.

She wrote their answers down on a big piece of yellow paper, and would go over them later as she read the story aloud to the sea of upturned faces.

Some responses: “There’s a mommy bear and daddy bear and baby bear.”

“The baby is laughing and they want to eat.”

“Goldilocks eats the porridge and the bear says ‘roarrr.’”

Smith praises them all.

Then Smith poses a new question of the day: “What do you know about clothes.” (Questions for each day are dictated by the district’s preschool curriculum, called Teaching Strategies.) It seems to be a big leap from Goldilocks.

But in fact, they are related. One thing you learn about clothes is what size they are. Several children say that you can read tags. And often that means seeing the letters S, M, and L for small, medium, and large.

That’s just like the story of the three bears.

“I love how y’all are putting on your thinking caps this morning,” Smith tells them.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.