“Personalized learning” is in — just look to the more-than-$5 million in grants Denver Public Schools has received in recent years to create new personalized learning programs for evidence. But just what makes learning “personalized,” let alone whether such programs work, is less clear.

A new report from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the RAND Corporation aims to define and analyze the practices and performance of schools focused on personalized learning. It concludes that while early efforts are promising, there remain practical and systemic barriers to expanding programs that aim to tailor instruction to individual students’ needs and skills.

“It seems theoretically like a good idea to let children work at their own pace and continue working on things until they get mastery on a topic,” said John Pane, a senior scientist at the RAND Corporation who led research for the report. “But it’s important to see if these schools did produce stronger takeaways than traditional schools.”

On that question, the report, ”Early Progress: Interim Report on Personalized Learning,” is cautiously optimistic. Researchers from RAND found that students in 23 personalized learning schools did better on a computer-based reading and math assessment known as MAP than peers in a control group, and students who started out behind were even more likely to show growth.

But the report notes that overall, it’s not yet clear whether the personalized learning programs are responsible for the gains. Other elements of the schools — all charter schools that use technology in instruction — might help explain the scores, the report notes.

“Clearly it’s not harming students,” Pane said. “And it might be a possible explanation for why they’re doing well. We need to do more work to decide.”

The researchers looked at schools that had been using personalized learning programs for at least two years and had gotten funding from the Gates Foundation or other philanthropies to support technology, professional development, and other elements of personalized learning, but each had designed its program independently. (Chalkbeat also receives funding from the Gates Foundation.)

Although not all of the features were in place at every school studied, researchers found that the schools tended to use:

- “Learner profiles,” or records with details about each student;

- Personalized learning plans for each student (students have the same expectation but have a “customized path”);

- Competency-based progression, in which students receive grades based on their own mastery of subjects rather than on tests that all students take; and

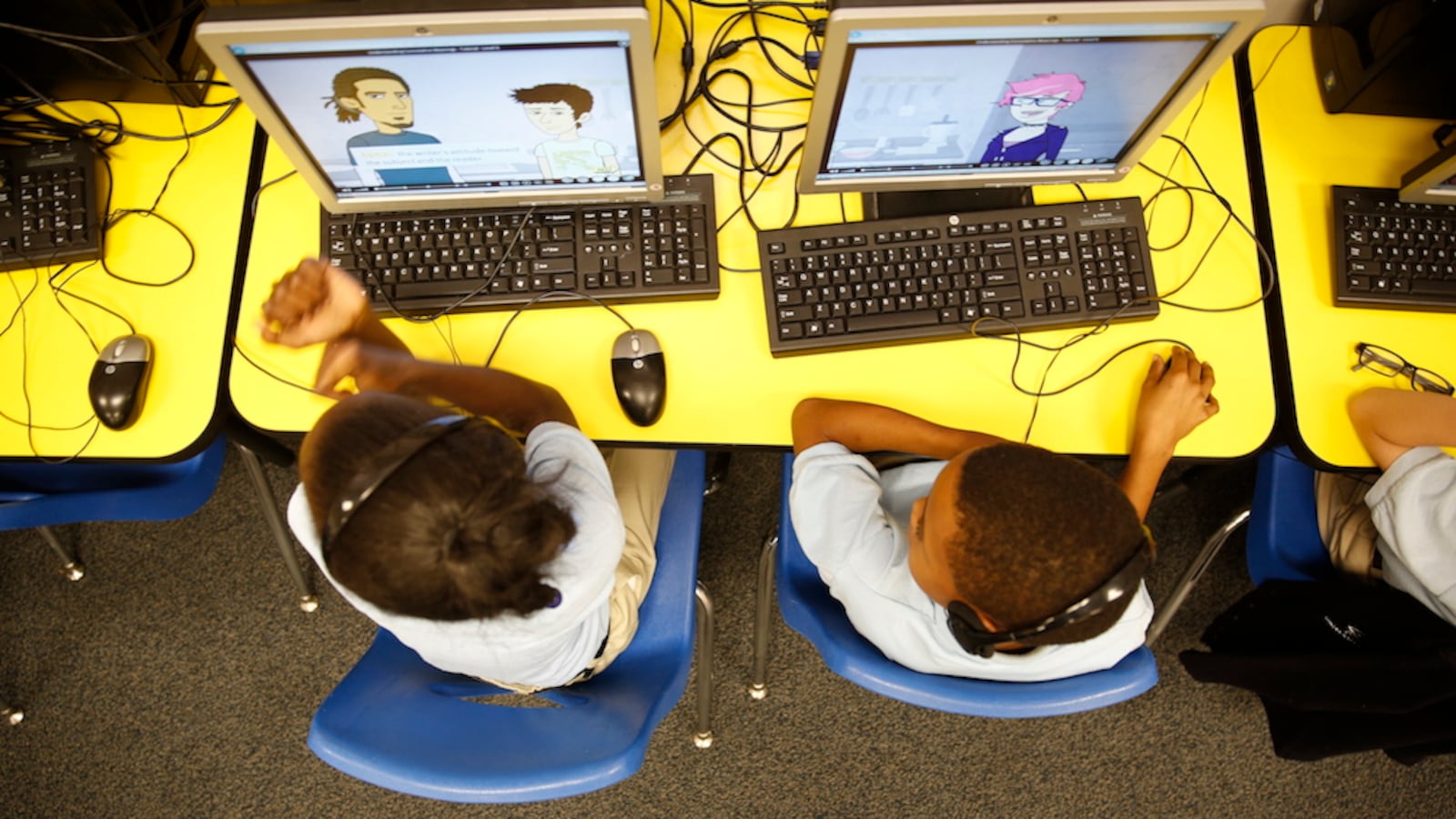

- Flexible learning environments, in which teachers and students have physical space and time in the schedule for small-group instruction or tutoring.

The report highlights advantages of personalizing learning beyond boosting test scores. Most teachers in the schools reported that they felt supported by administrators and that their professional development helped them tailor lessons to students’ needs.

It also notes areas where teachers said their schools’ personalized learning efforts fell short. Fully half of teachers said the training they got took up more time than it was worth, and only a third said they got data about their students’ performance in subjects other than math and reading. Others said discipline and absenteeism presented challenges.

In Denver, the district is considering creating several new personalized learning-focused schools, including one that would grow out of Grant Beacon Middle School.

Alex Magaña, the principal at Grant Beacon — which was not included in the Gates study — said that when his program adopted a blended learning program and focused on personalizing lessons to students three years ago, test scores and student engagement both improved. He said the school has built a bank of lessons and best practices for its teachers over time.

“Now we have people from around the country coming to visit us and sharing ideas, asking us, what does this look like?” Magaña said. “Because there is no model. That’s the fun part. We get to create it. Yet the gains are showing.”

Vicki Phillips, who heads the Gates Foundation’s U.S. education division, said the results in the 23 schools in the study “give us a sense of what’s possible.”

“We have a lot more to learn and a broader band of schools to see if this is more effective — and a lot more to do to really isolate what works,” she said. “But if we don’t talk about it, we don’t grow or mature as a field.”