The debate on testing, the most divisive education issue of the 2015 legislature, ended on the session’s last day with self-congratulatory speeches and strong votes for a compromise bill.

What matters for kids and parents is that the total time a student spends testing while moving from kindergarten to 12th grade will drop from about 137 hours to 102 hours, according to bill supporters. The biggest reduction will be in the high school years, and the changes go into effect for the 2015-16 school year. (See this chart for details by grade.)

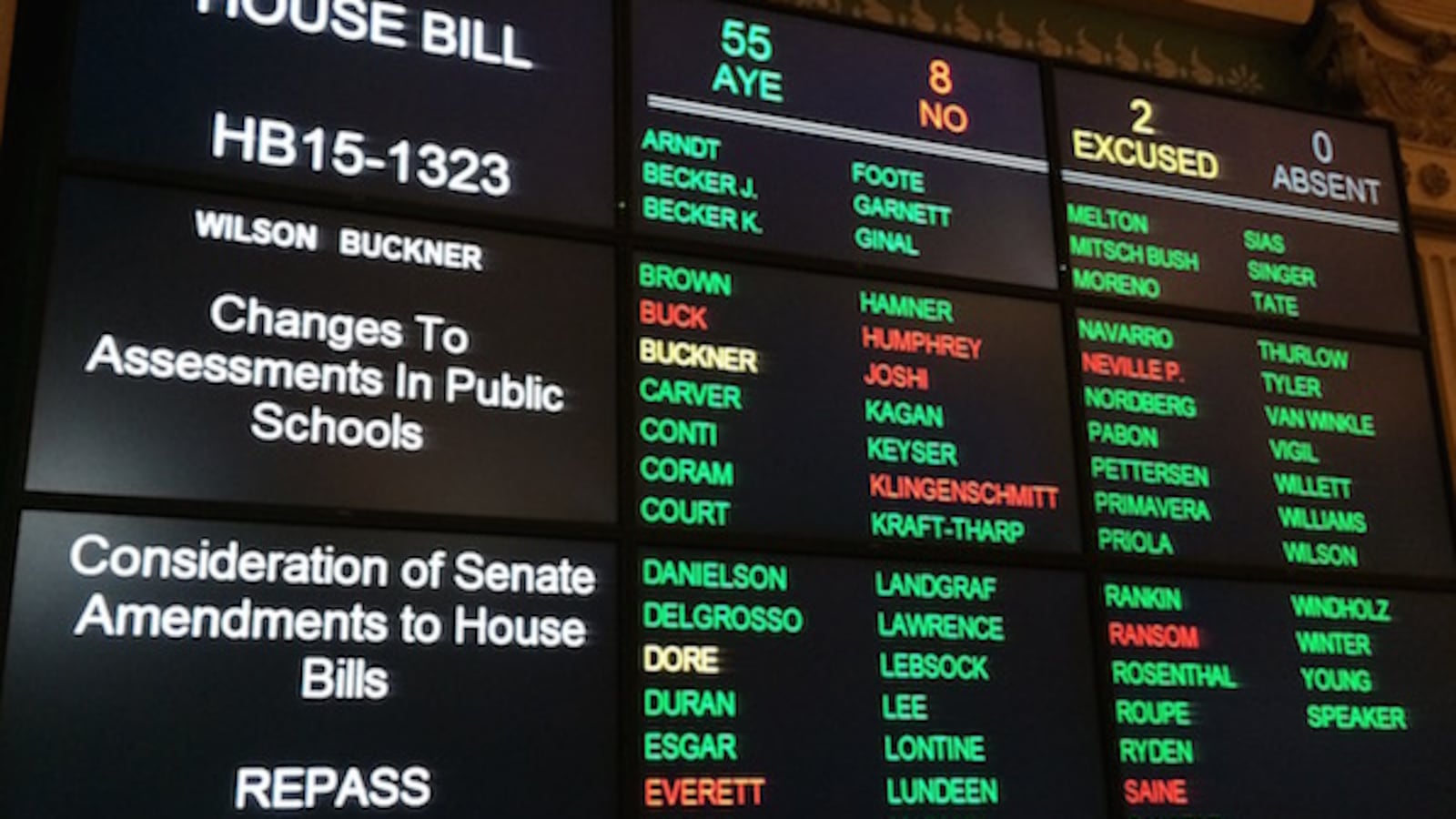

There’s plenty of grousing that the bill doesn’t go far enough. But in the end it was more than good enough for the legislature, judging by the tone of Wednesday’s speeches. House Bill 15-1323 passed the Senate 30-5 and the House 55-8 after that chamber agreed to final Senate amendments. (See the bottom of this story for the no votes in each house.)

The need to produce a testing bill and to avoid the political embarrassment of not passing one proved too compelling as the session drew to a close.

As usual, when a contentious issue is about to be decided, most lawmakers emphasized the positive in closing speeches.

In the 35-member Senate, 13 senators spoke for an hour on the bill.

“This has been a long journey and a lot of hard work,” said Sen. Chris Holbert, R-Parker and a key figure in crafting the compromise.

Senate President Bill Cadman, R-Colorado Springs, was the most effusive: “Something magic happened here.”

Representatives were brief, with only half-a-dozen members speaking for less than half an hour.

“On the very last day of the session we did it,” said Rep. Millie Hamner, D-Dillon and a prime sponsor.

Rep. Kevin Priola, R-Henderson and one of bill’s strongest GOP supporters, noted, “It’s probably been one of the more difficult bills this session. … It lightens the load where appropriate. It still maintains transparency and accountability.”

What the testing bill does

The compromise testing-reduction bill successfully walks a fine line between earlier proposals from the House and Senate.

The final plan makes changes both obvious and subtle in the Colorado Measures of Academic Success system, and its final shape remains to be determined, given that parts of the bill require sign-off by the federal government.

Two things definitely aren’t in the bill. It doesn’t withdraw Colorado from the Common Core State Standards nor from the PARCC multi-state tests. That’s a sore point for some legislators and activist parent groups. And the bill doesn’t reduce testing enough for the Colorado Education Association.

Here are the details on the compromise’s key points and how negotiators reconciled the differences between the two chambers.

High school testing – This was the big point of division from the start, and the recent expansion of CMAS tests into the 11th and 12th grades was the main spark for parent agitation and students opting out in the past year.

The federal government requires one set of language arts and math tests be given in high school. The House and Senate bills assumed that requirement would be met by 10th grade testing, but the two chambers disagreed over whether 9th grade tests should continue. Moving away from the assumption that full 10th grade testing was needed was a key factor in breaking the deadlock.

The compromise keeps the 9th grade tests but replaces the 10th grade CMAS exams with a college and workforce readiness test like the ACT Aspire. This test takes about three hours, compared to 11 for the two CMAS tests. Backers of the idea hope Aspire or something similar will be more relevant and therefore more attractive to students. Students will continue to take the main ACT test in the 11th grade.

Because the federal government doesn’t recognize 9th grade as part of high school, this provision will need federal approval.

One subtlety here is that because the two ACT-type tests aren’t part of the federally dictated CMAS system, student opt-out rates wouldn’t affect district accreditation ratings. Compromise supporters described this with the zen-like explanation that the tests are “not mandatory and not optional.” Districts have to offer them, but students don’t have to take them. The state would have to put the 10th and 11th grade tests to competitive bid every five years.

The current schedule of giving science tests one time each in elementary, middle and high school will continue, but it’s left up to the Department of Education to decide in which grades.

Opting out – The bill guarantees parents the right to opt students out of tests and that students won’t suffer any consequences or punishment for doing so. It also specifies that districts cannot discourage students from taking tests. Opting out was a hot topic at the Capitol this year, and variations of opting out language were offered in several other bills, including a stand-alone measure passed by the Senate but killed in a House committee.

Pilot programs – There’s been a push by some lawmakers and districts for the ability to give their own tests rather than the CMAS/PARCC tests. Current federal law requires a single test be given to all students in a state. The Senate and House were way apart on this issue.

The compromise allows any district or group of districts to apply to the state for approval to “pilot” new tests. Eventually two tests would be chosen from those pilots. And in the end the Department of Education – with legislative approval – could use one new set of tests statewide. (There are a lot of ifs in this plan, including at least three separate federal sign-offs.)

Timeouts – Both original bills had various provisions to protect schools and districts from accountability consequences of new test results and to change how growth data derived from results is used in teacher evaluations.

The compromise creates a one-year accountability timeout for school and districts in 2015-16. Teachers get a break on use of state data for their 2014-15 evaluations. In future years districts don’t have to use state growth data if it comes in too late to meet deadlines for finishing evaluations. Late data would be used in subsequent years’ evaluations.

Paper & pencil – The original Senate version proposed allowing both parents and districts to request paper tests. The House would have given that option only to districts. The compromise allows individual schools or districts to request paper exams. The goal here was to avoid having some students in the same class taking online tests while other kids used paper versions.

Social studies – These tests now are given once in elementary, middle and high school. They rolled out only a year ago and as such were part of the uproar about “over-testing.” A separate measure that also passed Wednesday, Senate Bill 15-056, creates a compromise. Instead of being given to every student in the three grades every year, tests will be given in selected schools. The goal is to have the test given in an individual school every three years.

There are several issues that weren’t disputed by the two houses and that were carried into the compromise plan. Those include:

- Requirements for notification of parents about the purposes and uses of testing and about testing schedules.

- Language increasing the number of years that native-language tests can be given to ELL students and recently arrived immigrants. (This also requires a federal waiver.)

- Streamlining of school readiness and READ Act literacy assessments, primarily eliminating some duplicative tests.

Many play a role in compromise, now and in future

The final testing bill was crafted to meet an iron law of Capitol math: To become law, a bill needs at least 33 House votes, 18 in the Senate, and one governor’s signature.

As noted above, the testing measure adds a fourth party to the discussion – the U.S. Department of Education.

Colorado’s overall system of tests and accountability is approved through what’s referred to as a “waiver” granted by the department. That agreement allows the state to do some things its own way rather than strictly follow the current Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

Changes in the state system by either the legislature or the state education department have to be reported to Washington through a process that – confusingly – also is called a “waiver.”

If the federal education department doesn’t like such individual changes, it could revoke the state’s overall waiver, potentially creating all sorts of administrative problems for CDE and districts. If a state is out of compliance with federal requirements it theoretically faces the loss of some federal funds, primarily grants to low-income students.

Hammering out an agreement

Lawmakers had a hard time all session coming to agreement on testing. Legislative leaders started moving things along last week.

Members of both education committees and other lawmakers met in the speaker’s office one evening last week to hash things out.

A smaller group of legislative leaders convened last weekend to keep the momentum going. Lobbyists and leaders from the full spectrum of education interest groups also were involved.

The plan started to take final shape at a meeting of about half-a-dozen lawmakers who gathered around the press table in the House chambers last Sunday afternoon.

But there was nervousness about the deal until the end. Sen. Andy Kerr, D-Lakewood, told his colleagues he was unsure as recently as Tuesday that things would come together.

“It’s been the most challenging work I’ve done,” Rep. Millie Hamner, D-Dillon, told Chalkbeat.

How they voted

Voting no in the House were GOP Reps. Perry Buck of Windsor, Justin Everett of Littleton, Steve Humphrey of Windsor, Janak Joshi of Colorado Springs, Gordon Klingenschmitt of Colorado Springs, Patrick Neville of Castle Rock, Kim Ransom of Highlands Ranch and Lori Saine of Firestone.

Voting no in the Senate were Republican Sens. David Balmer of Centennial, Kent Lambert of Colorado Springs, Vicki Marble of Fort Collins, Tim Neville of Littleton and Laura Woods of Thornton.

A separate but virtually identical measure, Senate Bill 15-257, was allowed to die as the session adjourned. It was the original Senate proposal, but both it and HB 15-1323 were amended earlier this week to be the same.

See this staff summary of bill as of May 5.