In a suburb just outside of Denver, Principal Sarah Gould stands outside a fifth-grade classroom at Hodgkins Elementary School watching students work. This classroom, she explains, is for students working roughly at grade level. Down the hall, there are two other fifth-grade classrooms. One is labeled “Level 2 and 3,” for students who are working at the second and third-grade levels. The other is for students who are working at a middle-school level.

But some of these students won’t necessarily stay in these classrooms for the whole school year. The students will move to new classrooms when they’ve mastered everything they were asked to learn in their first class. This can happen at any time during the year.

“We have kids move every day. It’s just based on when they’re ready,” Gould said.

Six years ago, Hodgkins Elementary worked the same way most schools and districts do: Students were assigned to a class for a fixed amount of time and were promoted when the time ended, assuming that they had gained the skills they needed for the next class — and sometimes even if they had not.

Now, the school is part of a growing movement toward “competency-based education,” which replaces “seat time” with skills as the main standard for whether students are promoted. Competency-based education goes by many names — mastery-based, proficiency-based and performance-based education — but the idea is the same: Students are measured by what they’ve learned, not the amount of time they’ve spent in the classroom.

Innovations in technology and how teachers can monitor students’ progress, along with changes to regulations about how long students must spend in class, have made it possible for schools and districts to adopt competency-based systems in an effort to use students’ time in school more effectively.

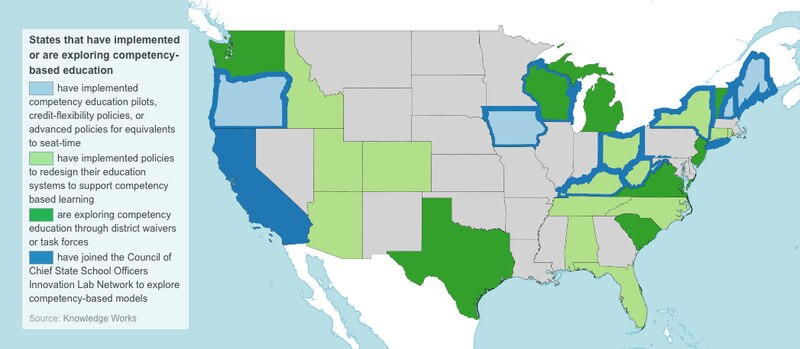

At least 40 states have one or more districts implementing competency education, and that number is growing, according to a 2013 KnowledgeWorks report with the most up to date numbers on the trend.

But competency-based education doesn’t look the same across the country. In fact, advocates say schools and districts fall on a “competency continuum,” based on which aspects of competency education they’ve implemented.

When advocates talk about a “pure” model of competency education, they describe a model that isn’t bound by grade levels or the Carnegie unit, a measure of the amount of time a student has studied a subject in class. At that end of the spectrum, schools like Hodgkins or New York City’s Olympus Academy have essentially gotten rid of standard K-12 grade levels and only move students to the next learning level if they’ve proven they’ve mastered the concepts. (The schools generally must track students by grade level for funding and state testing purposes, even if their classes are not designed for single-age cohorts. Some advocates, including officials in Hodgkins’s district, want state policies changed to allow competency-based learning schools to track students differently.)

“Education systems in the past have been notorious for jumping on bandwagons but nothing substantially changes under the surface. In our model everything has changed under the surface,” said Oliver Grenham, chief education officer of Hodgkins’s district, Adams County School District 50 in Colorado.

But at the same time, advocates acknowledge that the “full system overhaul” is a heavy lift and that schools need to start from a place that makes the most sense for them based on their time, resources, and community support. For some districts, the clearest path has been to create new schools based on the model, as Philadelphia did this year when it opened three high schools that assign students to “workshops” rather than classes.

The schools retain some of the traditional school organization, but are working toward replacing standard grading with a detailed, competency-based matrix that lets students know at all times where they stand and helps them understand their own strengths and weaknesses.

Traditional letter grades don’t give students much information about what they know and can do, said Thomas Gaffey, the technology coordinator at Building 21, one of the three Philadelphia schools. The competency-based evaluation he helped design “makes the learning process transparent,” he said.

More often, schools have nestled a competency-based philosophy within their existing operations, maintaining their grade-level arrangements while adapting how they assess student learning.

“We’re a hybrid, which is what I think appeals to people who look at our model,” said Brian Stack, principal of Sanborn High School in New Hampshire. “It’s not vastly different from what they do with a traditional model, but it’s not so far out on the spectrum that it’s unattainable for them to get to where we are.”

At Sanborn, students are still enrolled in traditional classes and still receive credit for class at the end of the year. But all the courses have defined core competencies and if students don’t gain those competencies, they have to do extra work in order to earn credit for the class, rather than simply accepting the lower grade. The school is also in the process of doing away with numerical grades in favor of a scale that ranges from “limited progress” to “exceeding expectations.”

“We grade kids every day,” Stack said. “The difference is, what are you doing with that grade? Are you using that as feedback to tell students how they’re doing and to inform instruction or are you just using it as a determination to say did they know it or not?”

Stack said as much as he would like for his school to be totally unbound by seat time, its model is still dictated by the school calendar.

“If we can’t move kids when they’re ready, we can at the very least try to personalize instruction to the extent possible when they’re with us,” he said.

Other schools offer their own reasons for maintaining grade levels while rolling out a competency-based approach.

After a competency-learning pilot in math yielded major gains for California’s Summit Preparatory charter schools, the network adopted the approach in most academic subjects — and considered going further.

“We thought eliminating grades was the gold standard ideal,” said Adam Carter, chief academic officer. “We thought, ‘Those stupid grade levels are holding us back.’”

That changed when Summit officials thought through what they would lose by doing away with grade levels and realized that students benefit by belonging to a fixed cohort that advances together. “If students can plug into a project that is rich and full of layers, we don’t need to get rid of grade levels,” he said.

Schools operated by Rocketship, a national charter school network, regroup students four to six times a day based on their academic skills, in a robust example of how educators can use student data to foster competency-based learning.

“But we still have grade levels because of the social-emotional needs of students, especially early elementary,” said CEO Preston Smith. “Five-year-olds need to be with 5-year-olds most of the day so they can develop the life skills they need to be successful.”

Advocates of competency-based learning say the diversity among schools’ approaches should be expected — and appreciated — as more experiments take shape.

“Each school and each district is on its own journey and they’re going to have different entry points,” said Susan Patrick, president of the International Association for K-12 Online Learning, which champions online and blended learning models that are often part of competency-based programs. “Most school leaders who are implementing this well … had been working on the building blocks for three to six years.”

Lillian Pace, senior director of national policy for KnowledgeWorks, said, “Naturally, you’re going to see a tremendous amount of diversity in implementation. … That’s healthy. We need to try different approaches. We need to figure out ultimately which methods are the most effective.”

For now, the experience of schools like Hodgkins suggests that competency-based education might help engage students in their learning.

When kindergarten teacher Jenn Dickman recently asked for volunteers to share their “data notebooks” with a visitor, her students rushed en masse to grab the binders.

Jayleen Vasquez was first in line. She flipped quickly through the pages—each a mini-progress report of her skills. At the top were headers such as, “I can read a Level D book with purpose and understanding” or “I can read 50 sight words in 100 seconds or less.”

Underneath were columns shaded in colorful crayon hues showing whether she’d met the goal, and if not, how much farther she had to go.

“I passed these. I got those two right and this one I just forgot one. I did not pass this one,” she said, gesturing to one page. Then she concluded with pride: “I passed all this.”

This story was produced as a collaboration among all news organizations participating in the Expanded Learning Time reporting project. Reporting was contributed by Sue Frey for EdSource California, and Dale Mezzacappa for the Philadelphia Notebook.