A one-year-old federal program that allows school districts to offer universal free meals at some or all schools is growing in Colorado.

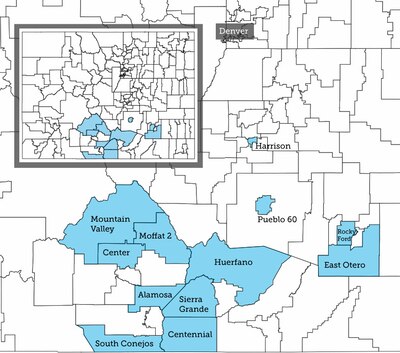

A dozen districts, most small and rural, are planning to participate in what’s called “Community Eligibility Provision” or CEP this year. The program, which no longer requires families to fill out applications in order for kids to receive free breakfast or lunch, launched with eight districts last year.

At the time, administrators in some eligible districts passed on CEP because of concerns it could jeopardize funding for at-risk students. A year in, that trepidation appears to have eased a bit.

CEP represents a shift from giving meals only to students who fall below the government’s income bar to all students in high poverty schools or districts. The goal is to increase access to school meals with the hope of reducing hunger and some of the issues that go along with it, such as spotty attendance or discipline problems.

Julie Griffith, program specialist in the state education department’s Office of School Nutrition, said CEP has been a good public relations step in the districts that have signed on.

“It is offering free meals to all students so there’s no barriers really,” she said.

“There’s no stigma attached…whereas maybe there used to be.”

In the 18,000-student Pueblo City Schools, administrators sat out CEP last year, but after much discussion this spring got the go-ahead from the school board.

Jill Kidd, nutrition services director for Pueblo City Schools, said in addition to making parents happy, she expects the program to increase meal participation by 5 percent districtwide and bring much-needed funding to her department. .

“I need refrigeration. I need upgraded electrical. I need ovens…I need new vehicles,” she said.

“There’s just not that kind of money in the district’s general fund to do those things, so this is an opportunity to get that kind of funding.”

The hitch in the giddyup

While CEP has the potential to achieve goals that food service directors strive for—feeding hungry kids and bumping up meal participation—it comes with a risk.

That is, the loss of millions in at-risk funding if districts can’t successfully transition from the old system of tallying low-income students to the new system under CEP.

The old system was based on counting free and reduced-price meal applications, which parents were required to fill out in order for their kids to receive free or subsidized lunches.

But under CEP, things are different. The application is gone, replaced by a similar form called the “Family Economic Data Survey.” The trick is ensuring that parents fill it out even though their kids get free meals either way.

Kidd said the possibility that parents won’t comply and the district will lose at-risk funding is the biggest con of CEP.

“The superintendent is still quite nervous about it,” she said.

Nevertheless, she said the district’s principals know the importance of collecting the new forms and there are procedures in place to ensure that it happens.

Low-income schools

Schools or entire districts are eligible for the CEP program for four years if 40 percent or more of their students are identified as low-income because they receive certain types of government benefits such as SNAP (formerly known as the food stamp program), or are classified as homeless, migrant or in foster care.

This “identified student percentage” is typically lower than a school or district’s free and reduced-price meal rate.

For example, Pueblo City Schools, the largest Colorado district participating in CEP this year, has an “identified student percentage” of 61 percent. In contrast, 72 percent of its nearly 18,000 students were eligible for free or subsidized meals last year.

While many districts don’t qualify for CEP on a districtwide basis, they are allowed implement the program in select schools that exceed the 40 percent threshold. That, however, has not been widely embraced in Colorado.

In part it’s because it requires two different systems of data collection to occur simultaneously—the traditional meal applications and the family economic data surveys. While a combined form is now available, there are still two sets of requirements to navigate.

Only three of this year’s 12 CEP districts–Harrison, East Otero and Rocky Ford—are opting for partial implementation. (All three districts qualify for the program districtwide, but stand to benefit more financially if they do it at their highest needs schools rather than all schools.)

Griffith said the education department’s goal for next year will be to recruit more districts for partial CEP implementation. This year the focus was districts eligible for full implementation, she said.

The deadline for CEP adoption this year is August 31.