For years, Greenlee Elementary has struggled more than most schools in Denver. Located in west Denver a block from the funky Santa Fe Arts District and exactly a mile from tony Larimer Square, many of its students live in the public housing that dots the neighborhood.

They face challenges that can make learning difficult but new principal Sheldon Reynolds sees the school as “a diamond in the rough.” A Denver Public Schools graduate, Reynolds has a plan to radically change the school’s culture — and the lives of its students.

Seven miles northwest, Centennial is three years into a redesign. After years of low test scores, the traditional K-8 school reinvented itself as an expeditionary learning elementary. It has a garden full of radishes and tomatoes, an outdoor classroom with log benches and an impressive cadre of parent volunteers who’ve already spent more than 2,000 hours at the school this year.

Under its new model, each grade has a theme, such as insects or plants, that provides fodder for project-based learning. For the first time, the principal expects a waiting list for kindergarten next year.

But under a policy unanimously approved by the Denver school board Thursday night, both Centennial and Greenlee could be flagged for potential closure, replacement or restart.

The policy, called the School Performance Compact, calls for promptly intervening when low-performing schools continue to struggle even after getting help. It’s in line with the district’s aggressive reform philosophy; over the past ten years, DPS has phased out, consolidated or shuttered 48 of its lowest performing schools, according to a district list.

“Historically, we’ve closed all types of schools,” Alyssa Whitehead-Bust, the district’s chief academic and innovation officer and a key contributor to the policy, told the school board at a meeting last month. “We have closed charter schools. We have closed district-run schools. But we haven’t always had the same criteria for how we do that.”

The policy is an attempt to erase any ambiguity, she explained.

“It gives clarity about what our expectations are and what will raise the red flags,” board member Happy Haynes said before the vote Thursday.

The policy calls for taking swift action with regard to schools that are “persistently low performing” but it doesn’t provide a definition of the term. That will come later, district officials said, when the superintendent develops a plan for putting the policy into practice.

However, DPS officials have floated one suggestion: schools designated as being in the two lowest tiers — “red” or “orange” — on the three most recent School Performance Frameworks, DPS’s color-coded school ranking system, or identified as red on two consecutive frameworks.

“Our experience has taught us that there comes a time after multiple supports over multiple years, when we do not see a school change trajectory, the kids in that school will be better off in a replacement or a restart,” Superintendent Tom Boasberg said at a recent meeting.

After all, supporters say, kids only get one shot at kindergarten, one shot at first grade and so on. “There are a number of our students who have languished in low-performing environments for a long time,” school board president Anne Rowe added. “The sense of urgency isn’t about going after communities or schools but about focusing on students.”

New possibilities

The low-slung, well-maintained brick building that houses Greenlee serves just over 350 kids in preschool through fifth grade. By any measure, the students there have higher needs. Nearly 92 percent of them are students of color and many are immigrants. About 94 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, an indicator of poverty. At Greenlee, that poverty is often generational and families move frequently.

Those challenges can lead to serious behavior issues, Greenlee staff said.

“Our kids are angry,” said Tania Hogan, a humanities coordinator who has been at the school for two years. “They let you know, too. You just have to work hard. But then once it breaks through — oh my gosh. That’s the reason I’m staying.”

Greenlee has been red on the three most recent School Performance Frameworks, despite years of turnaround efforts and funding. DPS schools were not given overall color ratings this year because the state switched to a new set of tests last spring. The framework relies heavily on student growth, which isn’t possible to calculate with only one year’s worth of scores.

But results from the new, more rigorous tests showed that fewer than three of the 46 Greenlee third-graders who took the English language arts test met or exceeded expectations. Scores in fourth and fifth grade were better but still below district averages.

Greenlee is trying to do better this year. It has a new principal, Reynolds, who returned to Denver after working on school turnaround and new school development in North Carolina. It has a new slogan: “Home of the Stars, Heart of the City.” And it has a new Possibility Plan, a multi-year roadmap developed by parents and staff for improving the school.

“There are some strong instructional elements here,” Reynolds said, “but it was getting to bring that culture piece back, to bring that pride in school.”

Instead of putting an emphasis on punishing bad behavior, Reynolds has created opportunities to celebrate students’ accomplishments. There have been awards assemblies centered around self-control and extra recess given to students who stay out of trouble.

On Monday morning, a group of fifth-grade boys rushed around, boisterously tidying the classroom of a teacher who’d recently returned from sick leave. They feverishly sharpened pencils, straightened chairs and alerted the teacher to a stinky rotten banana in one of the desks. Their efforts, Hogan said, were prompted by a schoolwide focus on kindness.

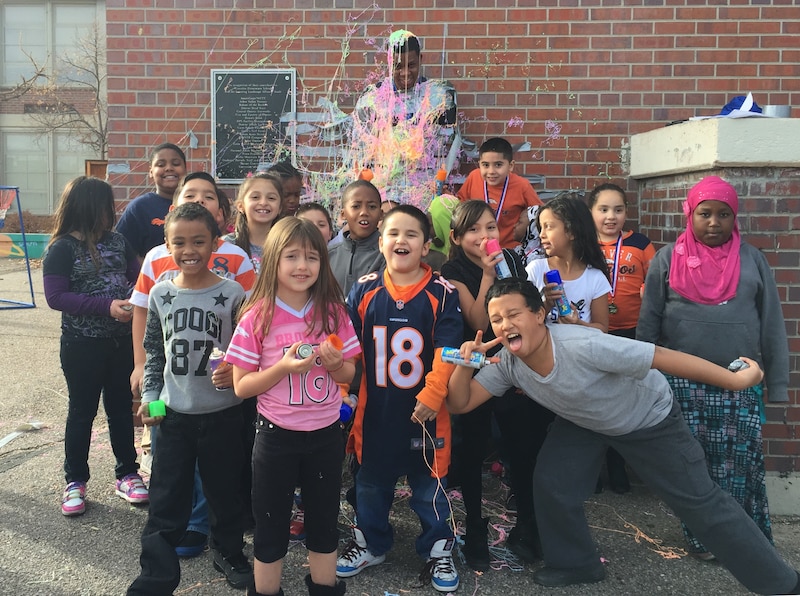

There have been academic rewards too. Recently, 27 kids who met their trimester reading goals got to duct tape Reynolds to a brick wall and spray him with silly string.

“The positive pieces have helped,” Hogan said, “and the kids go back and they’re like, ‘I can’t wait! What’s the next one?’ At this point, we need those little things. Eventually, our big goal is it’s all going to be intrinsic motivation. But right now, we need this to change the culture.”

The Possibility Plan also calls for distributing leadership responsibilities among the staff, giving teachers more planning time and tweaking Greenlee’s academic program. One idea is to have the school’s math and literacy fellows, who tutor students throughout the day, work with Greenlee’s higher performing kids instead of its lower performing kids so teachers who have more training and experience can provide deeper intervention for struggling students.

Reynolds hopes to increase the ways that the school helps families, too. Greenlee already has a clothing bank and participates in the Food for Thought program, which sends bags of groceries home with students on Friday afternoons. But Reynolds wants to do more.

“I really would love to see how I could do a birth-to-three push here. That wouldn’t show up immediately in a test score,” he said, but he believes it would pay off in the long run.

Reynolds said he always planned to make big changes this year. He started a school from the ground-up in North Carolina, and after learning of Greenlee’s challenges, he decided to approach his new job the same way. When he arrived, he learned from the staff that the school lacked a clear mission and vision. The Possibility Plan was meant to address that.

“I think the School Performance [Compact] just kicked us into gear a little bit quicker,” Reynolds said. “Instead of using it as something to make us worried, it was more like motivation.”

Now, Reynolds said he needs time. At a recent school board meeting, Greenlee teachers tearfully asked for the same. They said they understand the district’s desire to close schools that aren’t working. But what about schools that are trying to turn it around?

“How do you still have a process,” Reynolds said, “but then look at a school individually?”

Details to come

The answer to that question is expected to become more clear next year when the district finalizes a set of guidelines for how the School Performance Compact will be used.

According to the policy, those guidelines will spell out how the district responds to struggling schools from beginning to end. The policy directs the superintendent to come up with “a clear set of supports” for those schools, as well as criteria for deciding whether a school should be closed, restarted or replaced if the interventions aren’t working. The district will choose a replacement only after consulting with the affected community, the policy says.

The policy isn’t slated to go into effect until the fall of 2016. But a draft of the guidelines first unveiled at a school board retreat in September provides some insight into how it might work.

The draft indicates the district will look first at a school’s performance over time — in other words, whether it’s been consistently red or orange on the School Performance Framework.

If it has, the draft says, the district will look next at whether the school’s most recent test scores show academic growth. If they do, the school could be crossed off the potential closure list.

If they don’t, the school will undergo a School Quality Review, the draft says. Outside evaluators will visit to figure out whether the school is on the right track to raise student achievement.

That’s the part of the process that would take into account whether schools are making efforts to improve — and whether those efforts are showing promise, Whitehead-Bust said.

“That’s the purpose of the review,” she said. “You get a sense of what’s taking root in a school.”

In the past, schools that earned a red or orange rating have received a School Quality Review every two years, said DPS spokesman Will Jones. Schools that saw a significant drop in student achievement have also gotten reviews, he said.

This year, 15 schools received reviews. Greenlee was among them. So was Centennial.

Like Greenlee, Centennial has been red on the past three School Performance Frameworks. But that rating doesn’t reflect the direction the school is going these days, a group of parents passionately explained to the school board at a recent meeting.

“We’ve shown so much growth in the past couple years,” said Sarah Brunke, who has three kids at Centennial. “I ask of you to give us the gift of time and let us really show you what we’re worth and let us really show you what we can do.”

In 2013, the district ordered the school to undergo a redesign. The community got involved and in the end, Centennial was reborn as an expeditionary school where teachers in each grade weave their year-long “expedition” theme into their everyday lessons.

For example, on Monday afternoon, wiggly second graders with pencils in their hands and worksheets on their desks listened as their teacher raised her sweet-sounding voice over the murmur of the bright and airy classroom to ask them a question.

“What is it called when two gears work together?”

The students had just read a passage about gears, a topic unlikely to fascinate most 7-year-olds. But their expedition for the year is to become experts on simple machines.

A little girl dressed as the storybook character Eloise — in honor of the first day of Centennial’s Spirit Week — raised her hand.

“A gear train,” she said, pointing to the explanation in the passage.

The teacher lauded her and pushed for more. “How can we write that in a complete sentence?”

Since the redesign, Centennial has seen changes. Enrollment is up. The number of parents volunteering in the school and the number of hours they spend there has skyrocketed.

And state test scores are promising, said principal Laura Munro. Although only eight of the 40 third-graders who took the English language arts test last spring met or exceeded expectations, Centennial did better than in the past when compared to other elementary schools in DPS.

“We recognize that the scores still have a long way to go,” Munro said. “But there’s some positive momentum there with a test that was more difficult.”

Another factor may be influencing what’s going on at Centennial, as well — one that isn’t as present at Greenlee: Northwest Denver has seen a surge of gentrification, and more and more families are choosing to send their kids to Centennial.

In 2011, 81 percent of Centennial students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. This year, that number is down to 61 percent. The percentage of minority students has also fallen sharply.

Steven Nichols said he and his wife decided to send their 6-year-old son Will to Centennial after hearing good things. Before the redesign, they probably wouldn’t have considered it, he said. But they’ve been thrilled with expeditionary learning and with what Will is learning.

“The other day, they were drawing the patterns that bees dance in to show the other bees where the honey is,” Nichols said. “Then they were acting it out. They had kids pretending to be bees and walking in circles. It’s very much a school that gets kids up on their feet and doing things and not trying to memorize what a teacher is saying. It’s just the right way to do it.”

When Nichols heard about the School Performance Compact and learned that Centennial would be one of the schools on the chopping block if DPS follows the draft guidelines, he was shocked. “The red is a rating for a school that doesn’t exist anymore,” he said.

While he’s confident DPS will recognize that and save the school, he’s worried that even the whiff of closure could scare off the type of hyper-involved parents who are helping Centennial shine. “This policy makes Centennial look unstable,” he said, “which it isn’t.”

The policy directs the superintendent to make the first round of school closure recommendations by the end of November.