The time and money Colorado high school juniors have invested in ACT test preparation will not be for naught: The state is sticking with the time-honored college preparation exam this spring before switching to the rival SAT next year.

Interim Education Commissioner Elliott Asp announced the one-year delay Monday and provided more details about the process and decision-making behind the state’s planned move to the SAT, which a selection committee found was more in harmony with the state’s academic standards.

The delay is welcome news to district superintendents, educators, students and others upset at the prospect of having to prepare for an entirely new test on such short notice.

The announcement does not reverse the state’s shift to the SAT; that would require legislative action. Instead, it means that 11th graders will take the ACT this spring, while 10th graders will take the PSAT in preparation for the SAT next year. The state is doing away with PARCC English and math tests for 10th and 11th graders that only debuted last spring.

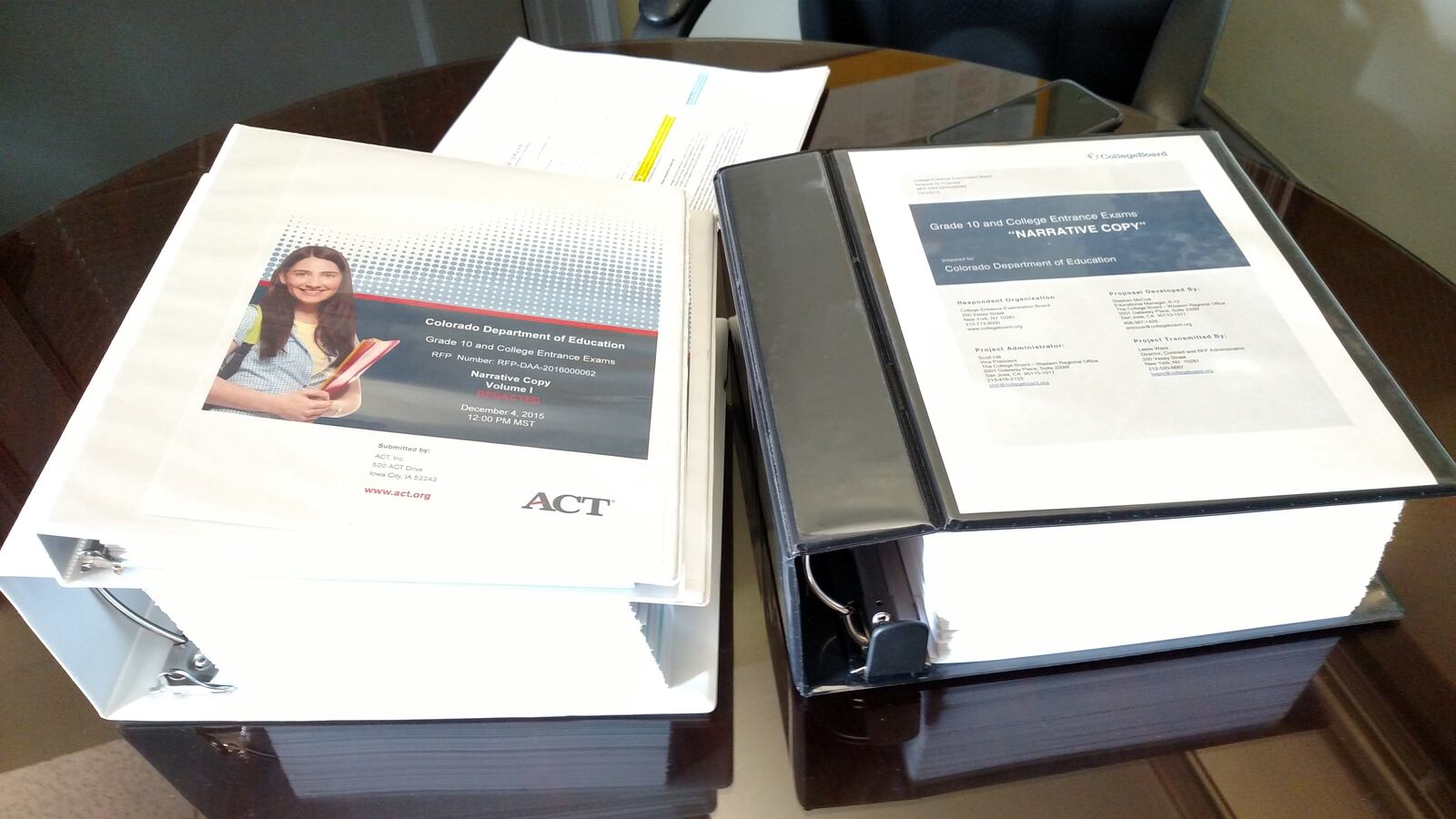

Asp said at a news conference that a 15-member selection committee charged with making the decision unanimously chose 10th and 11th grade tests offered by The College Board, makers of the SAT, over a bid from the ACT. The ACT has been given to Colorado 11th graders since 2001.

Asp said the committee — which included superintendents, district assessment coordinators, content specialists and others — determined that the PSAT and SAT are better measures of the state’s academic standards than the ACT and the ACT Aspire. He emphasized that the committee was far larger than the three or four people that typically would be involved.

Selection committee members | Jan DeLay, Superintendent of the Valley school district | Linda Reed, superintendent of Archuleta County school district | Kermit Snyder, superintendent of Rocky Ford school district | Johan van Nieuwenhuizen, Weld school district | Carol Eaton, executive director of assessment and research, Jefferson County School District | Julie Knowles, director of special programs at Garfield school district | Margaret Ruckstuhl, research, data and accountability officer, Harrison School District | Frances Woolery-James, secondary special education director, Cherry Creek School District | Patrick Kilcullen, priority programs coordinator, St. Vrain Valley School District | Cathy Martin, director of mathematics curriculum and instruction, Denver Public Schools | Kristina Smith, secondary English language arts specialist instructional support team, Mesa school district | Timalyn O’Neill, associate director of marketing and communications, Colorado State University Office of Admissions | Cory Notestine, counseling and postsecondary coordinator, Colorado Springs School District 11 | Sandi Brown, head of school, Colorado Early Colleges | Will Morton, director of assessment administration, Colorado Department of Education“I believe in the process,” Asp said in an interview. “I think it was done in good faith. I think the (selection committee members) were very deliberative and thought about it very carefully and ended up in a place of unanimous support that the assessments, in their minds — and they know a lot more about it than the rest of us — are the best assessments in the long run.”

Cost also was a factor, but not a major one, he said. That said, the difference was significant: The College Board’s bid to provide the tests over the next five years was $14.8 million compared to the ACT’s $23 million bid, officials said. Most of the cost difference came in the 10th grade test administration.

Points for equity

Selection committee member Julie Knowles, director of assessment and special programs for the Garfield School District in Rifle, said Monday she was swayed by the SAT’s alignment to the state’s academic standards and by free resources promised to students.

Those include personalized online test practice through Khan Academy, an app that feeds students SAT “questions of the day” and a partnership with the Boys & Girls Club that connects low-income students with those resources and others.

Knowles said those pieces — which ACT did not match — demonstrated a commitment to equity, serving all students and closing achievement gaps separating students based on their family income.

Joyce Zurkowski, the education department’s head of assessments, sounded a similar theme.

“College Board really presented a very convincing argument they are committed to equity issues and making sure all kids have access to preparation and activities and tools – not just kids who can afford to pay additional funds for that,” she said.

Colorado superintendents and others have mourned the loss of yet more longitudinal test data during a stretch when the state has adopted so many new assessments. Knowles said the committee extensively discussed the consequences of switching tests, and empathized with the concern about losing that data.

“High school is not the only grade level to lose its longitudinal data,” she said. “Third grade, fourth grade, fifth grade teachers have lost it, and so forth and so on. We have to remember why they lost it. We are trying to move to these new standards, and our assessments need to reflect these standards. High school is the final piece of the puzzle. If we don’t match the high school assessments to what is going on at the elementary level, we will have a big misalignment and do kids a disservice.”

Asp said education department officials have talked with both testing vendors and measurement experts about how to link scores from the competing tests to allow for measuring changes in student performance over time.

As part of sweeping testing reform legislation last spring, Colorado lawmakers required a competitive process for state tests given to 10th and 11th graders, setting up a high-stakes battle between two testing giants vying for the state testing market.

Any Colorado student remains free to take either the SAT or ACT. But the state will pay for only one of them, and the SAT eventually will become part of the system holding schools and districts accountable for student performance. Part of the rationale in making the ACT a statewide test more than 15 years ago was to get more students thinking about college.

A new SAT

The SAT is entirely new this spring, meant to better line up with the Common Core State Standards in English and math, which Colorado adopted. State officials and those more closely involved with the selection process credited the new SAT for asking students to read passages, interpret them and cite evidence — a critical piece of state standards.

Steve Lash, the longtime head of the honors program at Horizon High School in the Adams 12 school district, served on a panel of teachers who compared SAT and ACT questions to the standards, then reported its findings to the selection committee. Going in, Lash said he thought “we were going to justify our use of the ACT. I was surprised as anyone by the outcome.”

“We were struck with just how really different the tests are nowadays,” Lash said. “The SAT is superior now, especially on reading.”

The redesigned SAT puts much more of a premium on critical thinking, he said. Lash added that his group felt neither set of tests did an adequate job measuring writing skills.

Harry Bull, superintendent of the Cherry Creek School District, said districts need time to judge the new-look SAT. He said his “angst and anxiety” is not about the tests but about the decision-making process and how the move was announced.

State officials on Dec. 23 announced the decision to switch to the SAT starting this spring, and only hinted vaguely at working toward “flexibility” for this year’s junior class. Then on Jan. 4, the state announced it was working on letting students take the ACT again this year. Noting the uncertainty students faced, Bull called the approach “not very thoughtful.”

State officials say they recognized the challenges facing this year’s 11th graders from the outset, but had to follow state procedures and strike a deal with the two testing giants.

Bull was among a group of about 120 district superintendents who signed a letter to the State Board of Education last week raising questions about the process and decision. The letter suggested school districts were not consulted before a request for proposal was opened to interested testing providers, raising the possibility that procurement rules may not have been followed. Asp said officials followed proper procedure, talking to superintendents and others before the request went out.

ACT: no need for ‘knee-jerk’ change

Cyndie Schmeiser, The College Board’s chief of assessment, said in a statement that the test provider supports delaying the SAT administration another year, saying it is in the “best interest of students and educators.”

Paul Weeks, ACT senior vice president for client relations, said the testing firm was happy to continue giving the ACT in Colorado this spring, which he called an “unexpected ask.” But Weeks expressed disappointment Monday in the state’s decision to change to the SAT. He said ACT is confident in its assessments and continually improves them without resorting to “radical change.”

“We are not going to do anything rash,” Weeks said when asked about the ACT losing not just Colorado’s business but two other states’ in recent months. “We certainly are not going to engage in any knee-jerk change. When research and evidence is driving what you do, you have to be true to that.”

Both the ACT and SAT are accepted at all Colorado colleges and universities.

Click here to read a previous Chalkbeat story about the competition between the ACT and SAT in Colorado.