The Early Excellence Program of Denver shares a large brick building in the city’s Cole neighborhood with several other nonprofit organizations. Teaching Tree Early Childhood Learning Center is housed in a modest cream-colored building in a residential neighborhood in Loveland.

They are not the largest, wealthiest or biggest-name child care centers in Colorado. But they are the first two to earn the highest possible rating on Colorado Shines, a new mandatory state child care rating system meant to lift the quality of early education programs and better inform parents.

The centers earned the hard-won distinction by not only following best practices on everything from teacher-student ratios to financial record-keeping, but by completing an even more arduous task: proving it.

Childcare providers—and the coaches enlisted to help them—say that producing the detailed evidence required for the higher rating levels is tedious and time-consuming. Jennifer Luke, executive director at Early Excellence, said she felt like a lawyer preparing a big case as paperwork piled up in her living room in advance of the center’s rating last fall.

“It’s a huge audit, is what it is,” she said.

Despite the hard work required by the new system, Luke said, “Definitely, everything in Colorado Shines is beneficial for children.”

State officials say it’s only a matter of time before more centers nab the top rating—Level 5.

“I know we’ll see more eventually,” said Karen Enboden, manager of the Quality Rating and Improvement System in the state’s Office of Early Childhood.

A growing push to gauge quality

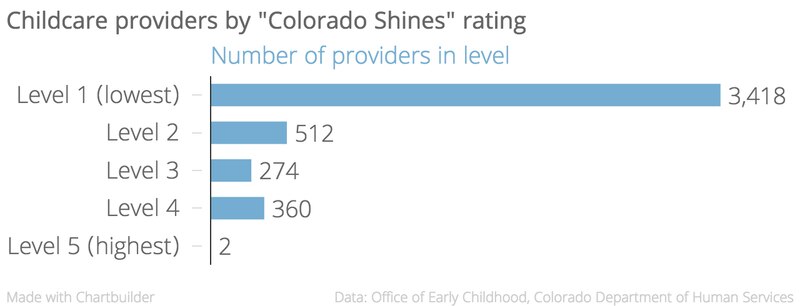

In the works since 2010, Colorado Shines launched last February and is mandatory for the state’s nearly 4,600 licensed child care providers—both child care centers and home-based providers. It replaces a voluntary system called Qualistar that was never widely used.

“It’s a time of massive change and it’s exciting to see it come to fruition in programs getting these higher ratings,” said Bev Thurber, executive director of the Early Childhood Council of Larimer County.

On a national level, Quality Rating and Improvement Systems have been the trend for more than a decade and experts laud them for incentivizing providers to make improvements and helping parents compare child care options based on a consistent standards.

In many states, including Colorado, such efforts have been paid for by Early Learning Challenge grants, part of the federal Race to the Top program.

Unlike the old Qualistar ratings, Colorado Shines ratings are free for providers. State officials say they plan to keep it that way even after Race to the Top funding runs out next December, or if the state receives a funding extension, December 2017.

In the first year of the program, the focus was on rating programs that had expiring Qualistar ratings as well as those serving the largest numbers of high-needs children, Enboden said. Early Excellence and Teaching Tree, as well as nationally known programs like Clayton Early Learning in Denver, serve many children from low-income families.

The lowest Colorado Shines rating is Level 1, which indicates only that a provider is licensed by the state and meets basic health and safety standards. The highest rating is Level 5, which means the provider has gone through an intensive process to demonstrate quality in everything from teacher-child interactions to business practices. Ratings through Colorado Shines are good for three years.

Providers that had Qualistar ratings were able to transfer into Colorado Shines with the same ratings. However, since the highest Qualistar rating was only four stars, no programs entered as a Level 5 in Colorado Shines.

That new level, along with various changes as program officials ironed out wrinkles in the new system, left even the highest caliber centers wondering if they could make the cut.

In fact, Teaching Tree didn’t earn a Level 5 rating at first. It came out as a Level 4, barely missing the top tier.

“We were so close to that 5. We were like a point away,” said Anne Lance, executive director of Teaching Tree, which also has a Fort Collins location that is now undergoing the rating process.

Last fall, state officials reviewed the scoring framework and made changes that helped put Teaching Tree over the top. The re-scoring process will also bump up ratings of other providers, though it’s not clear how many.

“There was some stringency in there that just didn’t make sense,” Enboden said. “We relaxed some of that.”

Burden of proof

On a recent Friday morning at Teaching Tree, lead toddler teacher Jodi Bell outlined the feet of her one-year-old charges on white sheets of paper.

For the youngsters, who then used markers to scribble on their outline, it seemed like a fun thing to do. But it was much more.

With a steady stream of questions and encouragement from Miss Jodi, they were practicing taking their shoes on and off and balancing on one foot. They were also starting to recognize their names and the personal animal symbols she drew on their papers. Finally, with its resemblance to a shoe-buying experience, the activity tied in with their unit on stores.

This type of engagement, also visible in the classrooms at Early Excellence, made administrators at both centers confident that they’d score well on the portion of Colorado Shines that examines learning environment.

However, there was more uncertainty around the other four standard areas: workforce and professional development; family partnerships, leadership management and administration and child health.

Partly it’s because having high-quality practices isn’t enough in Colorado Shines. Providers must provide detailed evidence in highly specific electronic formats.

“I’ve lost count of people saying, ‘I’m doing this…but I can’t prove it,’” said Soren Gall, an infant, toddler and family specialist with Denver’s Early Childhood Council.

Gall, like coaches at the the other 30 early childhood councils throughout the state, provides help to child care providers as they tackle the rating process.

Sometimes, securing the necessary evidence under Colorado Shines requires a small tweak— something as simple as instituting a sign-in sheet for parent events. But for other indicators providing adequate proof is more laborious—a major hurdle in a field where directors are often poorly compensated and stretched thin with day-to-day responsibilities.

In addition to offering one-on-one coaching to providers, state officials said many early childhood councils are also making technology equipment available to them in their offices or mobile labs.

Gall said while the new system is a struggle for some providers, particularly those who aren’t tech-savvy, he believes it represents a step forward for the field—getting away from the long-held stigma that childcare is just babysitting.

“This allows people to show that it’s a profession. It’s a business. It’s worth the time and energy and funding,” he said.

What the future holds

With Colorado Shines approaching its first birthday, state officials say the system is in good shape, even after the course corrections of the first year.

Enboden noted that 25 percent of the state’s providers have earned a Level 2 rating or higher—in other words they’ve made some effort above the basic licensing requirements. In contrast, only about 10 percent of the state’s providers chose to seek a Qualistar rating, all of which exceeded licensing requirements.

“Of course, with those statistics we’re feeling great,” she said. “Generally speaking, we are getting really good feedback from providers.”

Educating parents about the system is one of the key goals for the coming year. In addition to updating the existing English-language Colorado Shines website, the state will launch a Spanish version. It will also continue statewide print, radio and television advertising about the program.

“Parents are still not fully informed about Colorado Shines,” Thurber said, “but I fully expect over time parents will understand more about how to judge quality.”