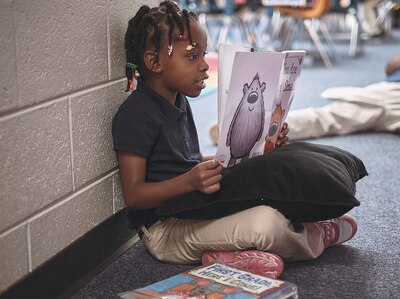

The staff at McGlone Elementary School has a mantra: Happy kids learn more.

It’s why the extended-day school in far northeast Denver offers nearly two hours of specials like art and music per day, why the cheerful and affectionate principal keeps a few “golden tickets” clipped to her lanyard to give out as rewards and why the classrooms aren’t the hushed, sit-up-straight, no-excuses type you might find elsewhere.

On a recent afternoon, two fifth grade boys in matching navy polo shirts and spiky hairdos huddled next to each other in teacher Matt Johnson’s math class. Sharing a single notebook page, they worked to solve 1 divided by 3, their skinny elbows pressed together in the unselfconscious way of elementary school students.

“It should be three halves!” one exclaimed.

“Why?” the other asked.

“Oh, wait!” the first boy cried out. “Thirds!”

McGlone’s joyful philosophy seems to be working. Once one of the lowest performing schools in the city, its impressive academic growth has turned it into a district darling. Then-U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan toured the school last spring, and the district recently made a video about McGlone after its students showed remarkable improvement on state literacy tests.

But McGlone wants to do more. In a district that values innovation and encourages its school leaders to think like entrepreneurs, the Montbello neighborhood elementary school — where 97 percent of the students are minorities and 95 percent are living in poverty — is asking to expand to serve sixth, seventh and eighth graders.

It’s somewhat of an unusual request. But leaders say that McGlone graduates who are used to a nurturing environment where hugs are as common as hellos are struggling at the area’s secondary schools, many of which follow a sixth-through-12th-grade model.

“I wonder if the system we have set up right now tells us that childhood in Montbello is over at age 11,” said principal Sara Gips Goodall. She hates to think of her babies, as she calls them, losing their way.

“I think our success hinges on kids feeling so supported and so loved.”

********

Five years ago, McGlone was among the worst performing schools in the city. It was ranked red, the lowest category in Denver Public Schools’ color-coded school rating system — and it wasn’t the only one in far northeast Denver.

In late 2010, DPS took drastic and controversial action in that part of the city. For McGlone, that meant undergoing “turnaround,” an attempt to transform the school with the help of more money and a new staff but without shutting it down and starting from scratch. Teachers at McGlone had to reapply for their jobs; only a handful were rehired.

School turnarounds don’t always work. Some DPS turnarounds have continued to flounder. But McGlone has shown progress.

Today the school is ranked green, the district’s second-highest rating. It’s gone from a place where only 10 percent of teachers stayed year after year to one where 90 percent do, according to its own statistics, and its enrollment has increased by more than 150 kids.

While McGlone’s test scores have risen, they’re still below district averages. Just 20 percent of students met or exceeded expectations on state literacy language arts tests taken last spring, compared to 32 percent districtwide. But McGlone kids showed more academic growth in literacy last year than any other elementary school in Denver, according to the district’s number crunching.

“This school was really, really low — and now we’re the highest,” said fifth grader Luis Salcedo.

McGlone’s math scores were similar: 17 percent of students met or exceeded expectations versus 26 percent districtwide. But McGlone students showed growth there, too.

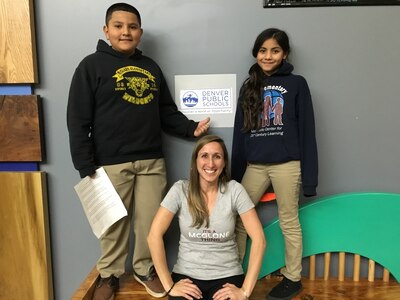

Salcedo and two other students led a recent school tour past bulletin boards festooned with test data, a science class where kids eagerly awaited the arrival of fish and snails for an experiment, and a gymnasium full of screeching first and fifth graders playing tag while Katy Perry blared from a set of speakers. When the teacher blew the whistle, the kids plopped down in rows and recited the names of different muscles. “Abdominals! Abdominals! Abdominals!”

“The teachers are always having your back and always teaching you what you need to know to pass the test,” said another fifth grader, William Campos, who has attended McGlone since preschool — before the turnaround. “And you always feel safe. And proud of coming in.”

“Before, the teachers would scream at the kids and the kids would run around,” said fifth grader Rebecca Cisneros, who’s also been there since preschool. “But now I feel like it’s more stable and safe.” When asked why, she offered this: “I guess because of Ms. Goodall.”

********

Goodall came to Denver in 2008 as a Teach for America teacher. She was assigned to Godsman Elementary, a high-poverty school in the southwest part of the city. She ended up staying three years, a year longer than was required, before leaving to attend the Harvard School Leadership Program, where she interned at a Boston turnaround school.

Eager to apply what she’d learned in a city she’d grown to love, the native East Coaster returned to Denver and started as an assistant principal at McGlone in the fall of 2012.

McGlone had become an innovation school the year before, meaning it was granted the flexibility to do things such as extend its school year and school day to help kids catch up. Students were making academic gains, but the school’s culture had taken a hit, Goodall said.

“Kids were angry,” she said. In addition to mandatory uniforms and a longer school day, she said, the students were being taught by new teachers who were asking them to work harder.

That year, Goodall met with a group of teachers and asked them what she saw as an important question: How can the administrators support you in building a better school culture?

They ended up writing a culture plan that includes monthly assemblies where both kids and teachers give shout outs, as well as several new recognitions and awards. The biggest is the Pack Leader (McGlone’s mascot is the Lobos), which students earn “for being a really good kid,” Goodall said. The Pack Leader isn’t necessarily the highest grade getter but is someone with good attendance who tries hard, shows improvement and has pride in the school.

“We’ve done tons of different stuff to say, ‘You matter as a person as well as a math score,’” she said.

When Goodall became principal in 2013, she started double specials blocks. Instead of back-to-back math blocks, students might get math followed by art, music, physical education, science or technology. The schedule has several benefits, Goodall said, not the least of which is fun. More fun, she believes, leads to happier students, which means fewer disruptions and more learning.

“Your math class is going to be better because you had a great arts block,” she said.

It’s also a way to keep kids coming, even if they’re dealing with tough situations at home. “They have to have a reason to love school,” Goodall said, “and sometimes it’s not reading groups.”

Meanwhile, classroom teachers use that time to dissect student data and plan lessons. Goodall prizes professional development, and teachers said they’re not afraid to ask for help.

“You can walk into any room and ask anyone anything,” said fifth grade teacher Lizzie Newcombe. “For me, as third-year teacher, I’m still kind of starting out. The amount of expertise and collaboration is incredible.”

McGlone was one of the first schools in the district to have teacher-leaders, who spend half their time teaching and the other half coaching other teachers. This year, Amy Lovell is one of them. A former first grade teacher, she splits her time between providing intervention for struggling readers and observing teachers and helping improve their instruction.

“We just kind of look at our kids and really try to figure out what motivates them,” she said. “We’re not traditional in that sense of, ‘Everyone turn to page 5, read together and answer questions.’ Every classroom knows their students’ strengths.”

Instructional superintendent Tanya Carter, who oversees McGlone and three other turnaround elementary schools in the far northeast, said she thinks the combination of strong academics and culture has made McGlone successful. Not every school does both well, she said.

“I think of the word ‘family’ when I think of McGlone,” Carter said. “They really do believe they are a family.”

That feeling, in addition to McGlone’s academic improvement, has changed the way the Montbello neighborhood views the school.

“A few years ago, I’d say (my kids went to) McGlone and it was like, ‘Oh, I’m sorry,’” said Shina Leonard, a paraprofessional at McGlone who has three kids who currently attend the school. “Now I say, ‘Oh, they go to McGlone,’ and it’s, ‘How do I get in?’”

********

Goodall and her team have already told DPS that McGlone would like to add a middle school.

But getting one isn’t that easy. The district, which is the largest in the state and getting bigger every year, has a formal process for soliciting ideas for new schools. It’s called the Call for New Quality Schools, and the most recent one was published last week.

It calls for a new middle school in the far northeast that could open in the fall of 2017 with space for 450 students. Residential development is booming in that part of the city — and many of the new houses are single-family, which tend to yield more schoolchildren.

The district is also asking for an additional 180 to 270 middle school seats by 2017 or sooner. That’s not enough to warrant an entire new school, but the district’s request says those seats could be added to an existing school, provided it’s a top-performing one.

McGlone wants to help fill those needs. School leaders plan to submit a formal letter of intent next month and an application by April, as is required by the process. The school board will vote to approve the school ideas, and where they’ll be located, in May and June.

McGlone is already at capacity this year with 730 students. To expand would require some construction. In the meantime, Goodall has an idea: she’d like to add two sixth grade classes this fall, making room by having the two assistant principals also share her small office.

But DPS hasn’t given the interim proposal the green light, she said. Until it does, Goodall has no choice but to advise her fifth grade parents to choose other schools for their kids for sixth grade.

Leonard is one of them. Her son, Damien, started at McGlone in kindergarten the year before the turnaround began. He left school that year not knowing how to write his name. Leonard was ready to switch schools but the staff pleaded with her to give turnaround a chance.

She’s glad she did. By second grade, her son had caught up. Now, his test scores are above average. But she’s worried he’ll slip again in middle school.

“These kids form their groups of friends, they feel safe, they know what’s expected of them and then you break them all apart,” she said.

The 28 students in one former McGlone fifth grade class ended up at 11 schools.

“A lot of kids fall through the cracks,” Leonard said. “That’s my biggest fear.”

Danielle Case has watched her 13-year-old son struggle after leaving McGlone two years ago.

“He had built such a good relationship with all the teachers there that when it came time to go to a middle school, it was really hard,” she said. “His friends didn’t follow him to the school that he selected. That caused a lot of depression for him and he started getting bullied a lot.”

When her son heard about the proposal to expand McGlone, Case said, “he kept saying, ‘I wish that was there when I was having to go into sixth grade.’” He continues to keep in touch with the teachers at McGlone, she said, even visiting them after school and over the summer.

Stories like that are all too common, Goodall said — and all too painful to hear.

“I’m really proud of everything our school has done,” she said. “It’s still not enough.”

That’s why on a Thursday night in December, a week before Christmas, dozens of McGlone teachers, parents and students filled the gymnasium where the DPS school board holds its monthly meetings. Dressed in maroon and navy McGlone T-shirts and toting hand-drawn signs, they waited to address the board.

Johnson, the fifth grade math teacher, told a story about one of his students, named America. The girl had tried to stall taking a tough test by complaining she had to go to the bathroom.

“‘Well, Miss America, we’ve only been here for about five minutes,’” Johnson told her. “‘Do you need to go to the bathroom or do you want to go to the bathroom?’

“Well, Mr. Johnson,” she replied. “What’s the difference?’”

Eventually, Johnson said, America admitted that she wanted to go to the bathroom — and she didn’t want to take the test because it was “boring and hard.” He thanked her for her honesty and then asked another question: But do you need to take the test? Yes, America said, because she knew that understanding math would help her be successful in life.

“I tell you this story because at McGlone, we don’t always give you what you want,” Johnson told the board. “But we definitely make sure our students have what they need. And right now, what we we need is a middle school.”