Rosemarie Allen knows that black students are disproportionately suspended and expelled from preschool and the K-12 system.

As the former director of the state’s Division of Child Care and now as a professor of early childhood education at the Metropolitan State University of Denver, she’s worked to address the issue for years. But she also experienced the phenomenon firsthand while growing up in California.

She talked with Chalkbeat about her own experience with school discipline, how unconscious prejudice impacts teachers and what can be done to address suspensions and expulsions in early childhood settings.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get interested in the topic of suspensions and expulsions?

I was suspended from school from the time I started kindergarten…at least five to seven times a year. I was expelled from three schools. It was the strangest thing because I knew instinctively I wasn’t bad and I couldn’t figure out why I kept getting in trouble.

I was really curious…Digging a big giant hole in the middle of the playground because the teacher said China was at the other end. Taking off all the baby dolls’ heads to see how the eyes worked.

After years of getting in trouble, what was the dynamic between you and your teachers?

After awhile I didn’t try anymore. I knew what they expected and we all resented each other. One time, we were having a math test and the teacher gave me the lecture: “If you get out of your seat just one time for any reason, you are going to get a big fat F. Do you understand?”

I took the test and finished really fast and I don’t know if I dropped my pencil or I threw my pencil, (but) I got up and got it. She came over and she put a big fat F on my paper. I was about 10.

By this time we were already in a power struggle. So, I said, “That’s OK. You know I got an A and I know I got an A.” So I took the F and (turned it) into an A and that infuriated her. She said, “If it goes in my grade book, it’s an F.” And with a red marker (she) put an F in the grade book. Me, being the kid I was, took the grade book and threw it out the window.

Given your history of suspensions and expulsions as a kid, how did you overcome that negative trajectory?

I had the most amazing, supportive extended family. Even when I was in trouble they always made me know I was smart. Now, when I did something wrong, when I got home I was grounded, but it didn’t define me.

How did your perceptions of your early struggles with discipline change when you started your doctorate program?

I realized it was not me at all. It was a sign of the times. I was the first generation after Brown vs. Board of Education where I had white teachers who did not have experience dealing with African-American children.

What do young children, especially young black children, typically get suspended and expelled for today?

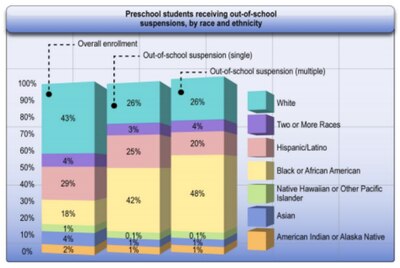

What we’re seeing is young black boys are engaged in either the same behaviors or even lesser offenses than young white boys, but the implicit bias of teachers doesn’t allow them to see it. They’re saying they’re disruptive, defiant, too active. Even if you go through 12th grade those are the reasons.

In my research, we see teachers judge black children based on stereotypes. When you believe a stereotype you see what you expect. So, you have a cultural disconnect, implicit bias and teachers not knowing how to handle what they call challenging behaviors.

My favorite saying is “behavior is defined by the person most annoyed by it.” If you already have this unconscious bias that we all have, then that behavior from that child annoys you even more.

You once observed a kindergarten class where a black boy was singled out for misbehavior by a teacher. What happened?

She was trying to get the children to sit criss-cross applesauce and they’re not. And the little guy I’m observing…he runs over and sits criss-cross applesauce.

The little white boy sitting right next to the teacher pulls his shirt over his head. He’s flipping. He’s turning. My little guy has been sitting and trying to get (the teacher’s) attention forever and he’s not getting it, so he unfolds his legs and he sticks them out and she has to reach over (the white boy and a white girl) to tell him to put his legs back. And you wonder does she see the kids next to her? Does she see the little girl twirling? For every four times she corrects (the black student) she says maybe one thing to the other two.

Did you have a chance to show the teacher the video you took of that incident?

Neither she nor the principal would look at the video. It was heartbreaking. The mom (of the black student) ended up taking him out. She was being called three or four times a week to pick him up.

Even though we’re seeing these amazing numbers of suspensions, what we’re not able to capture is what we call the “soft suspensions” — forcing them out; asking them to leave; saying, “This isn’t a good fit.”

What do you think caused the teacher you observed to focus so much on the black student’s behavior?

The biggest problem is the teacher didn’t know what to do. She had very little experience working with young children.

There are studies that talk about implicit bias and how it’s triggered most often with the automatic responses that are made under stress…So, she’s under stress. Here I am observing her room, (there are) 22 children who will not sit criss-cross applesauce and she tried to make them do it for 25 minutes. That’s where the implicit bias comes in: “Who are my troublemakers?”

What are the consequences for children who are suspended or expelled?

By the time they get to kindergarten and they’ve been kicked out of about two or three facilities, now they’re already disengaged from the learning process. And the greatest indicator of being suspended is having been suspended before.

Academic outcomes are definitely lowered. They’re disenfranchised even from other kids because now they’re labeled “bad.” So, not only are they in an “out” group because of race or gender, they’re in an “out” group because they’ve been identified as “bad.”

These kids have a lot of trouble…having positive relationships with teachers and with other children and sometimes at home.

How early do suspensions or expulsions start?

My research shows it starts about 17 months and usually it’s for biting or aggressive behaviors. Even that young there’s disproportionality. We’re seeing all the children are biting, but black boys are being suspended or kicked out.

How do you facilitate cultural competency in your classes at MSU Denver?

Ninety-five percent of my students are white women. Most of them, by self report, have had very little interaction with people of color. We take them on these field trips (to a black church, a Buddhist temple, Denver’s Five Points neighborhood etc.) where they are now engaging with people from backgrounds they’ve never had exposure to.

You once visited a family child care home run by a man who offered unusual opportunities for movement and physical activity. How did that shape your thoughts on the mostly female early childhood workforce?

I began to see how careful we are: “Don’t jump! Don’t run!” How much we stifle the natural activity of boys. I began to see that as women, we want boys to act like girls because then we can be in a lot more control.

You’ve said that everyone has implicit bias, including you.

As long as I’ve been doing this work, I’d say at least two or three times a week my biases pop up.

My classroom was observed when I was a young teacher and the observer said I was biased against little girls — one of the most devastating events of my career. She didn’t say, ‘You’re biased.’ She said, “Rosemarie, do you like little girls?’ And I said, ‘Of course I do, I love all my children.’ She goes, ‘Well, little girls tend to get in trouble a lot with you, more so than little boys.’

My daughter said this was my PTSD because … when I was in trouble (as a child), it was always the little girls who tattled on me, so I had this built-in bias.

How does public policy need to change on early childhood suspensions and expulsions?

I believe as long as we have suspension in our tool box, we’ll use it. You’ve heard the saying, “If the only thing you have is a hammer, then everything looks like a nail.” And we want to get rid of the hammer, but we can’t do that if teachers don’t have the support they need.

The last thing we want is for a child who’s perceived as a problem to be forced to stay in an environment where they’re not wanted, because then I would fear abuse, no matter how subtle that is.

So, I think the first thing we need to do is make sure teachers have the tools they need. They need training on implicit bias. They need professional development on how to handle some of these behaviors.

My contention is in order to reduce disproportionality we have to be aware of the biases, the culture and the expectations that we bring into every situation. And it’s just there for all of us, whether it’s the gender gap, the racial gap, class gap.

What is the next thing Colorado should do?

It’s two pronged: Create the policy that says if suspension is ever used it will be used as a last resort and it will be determined by a third party. And teachers get the supports they need.

The key is that we recognize that people are in this field because they truly want to make a positive difference and impact outcomes for children. No one is coming in saying I want to suspend little black kids or little brown kids. They are doing the best they can with what they have. I think that’s the first thing we need to recognize. But then say, “But here’s the data and we know why that’s happening.”

I think providers are afraid they’re going to be perceived as really bad people. We don’t want that. We know that there are tools out there that can help: Pyramid Model practices, early childhood mental health consultants and teacher prep programs. The Denver Preschool Program has a four-part training series on addressing disproportionality in discipline.