A little ponytailed girl gave her preschool classmate a hug. Then it became more of a boa constrictor’s squeeze. Her friend began to cry. The girl moved on, hugging another classmate so enthusiastically they both fell over onto the carpet at TLC Learning Center in Longmont.

It’s the kind of thing that can get little kids in trouble at some preschools and child care centers—and in the most serious and chronic cases removed from their classrooms and schools.

That doesn’t happen at TLC, thanks in part to Pam Sturgeon.

The early childhood mental health consultant is part of a growing group of specialists charged with helping early childhood teachers handle challenging behavior among students—whether it’s biting, hitting, over-hugging or some other problem.

Sturgeon, who visits about a half-dozen Boulder County schools and child care centers each week, is on the frontlines of Colorado’s efforts to prevent suspensions and expulsions in early education. It’s an issue that’s gained national prominence recently, particularly in light of data showing that black children, especially boys, are disproportionately affected by such practices.

Since 2006, 17 early childhood mental health consultant positions have been funded through Colorado’s general fund. That number will soon double thanks to a $1.4 million infusion from the state’s child care block grant approved by the legislature last winter.

Jordana Ash, director of early childhood mental health in the state’s Office of Early Childhood, said the decision to expand the program grew out of increasing concerns about preschool expulsions, a growing emphasis on children’s social-emotional development and efforts to include kids with disabilities.

She said some of the state’s current consultants cover up to 10 counties.

“The capacity needs in our state have long been underserved by the 17 that we have,” Ash said.

Growing momentum

Colorado’s expanded cadre of 34 state-funded consultants represents one of the nation’s largest state investments in the approach. (Officials say there are an additional 20-30 consultants in the state funded through other sources.)

Arizona, which pays for its program with state tobacco tax money, has more publicly funded consultants, Ash said.

“This is a program states have struggled to figure out how to pay for because these are preventive services,” she said.

Colorado’s new investment in mental health consultants is not the only effort to help child care providers deal with challenging behavior and head off suspensions and expulsions.

Several programs around the state provide extensive teacher training on children’s social-emotional development. These include Pyramid Plus, The Incredible Years and “Expanding Quality for Infants and Toddlers.”

In addition, new state rules took effect in February requiring licensed child care centers to spell out how they’ll handle challenging behavior, make discipline decisions and access consultants.

Day in the life

Most of Colorado’s state-funded early childhood mental health consultants are based at community mental health centers. Some also work through early childhood councils or Boards of Cooperative Educational Services, which provide services to multiple member school districts.

Sometimes, consultants work with child care staff to promote social-emotional skills before problems arise. Other times, they’re called late in the game when expulsions are imminent.

Even then, they can help diffuse built-up stress and slow down or stop the expulsion process, said Matt Powell, who oversees three consultants including Sturgeon through Mental Health Partners’ Kid Connects program.

Early childhood suspensions and expulsions are worrisome because they can have long-term consequences for kids—not only increasing the likelihood of future suspensions and expulsions, but also the prospect that students will struggle academically, drop out of high school and even go to prison.

Some of Colorado’s consultants are “embedded,” meaning they spend significant time at a particular center. That’s the case for Sturgeon, who spends about two days a week at TLC, a Pyramid Plus center where 40 percent of students have special needs.

In addition to training staff, she visits classrooms and talks with parents about promoting children’s social-emotional skills at home.

During a recent morning at TLC, Sturgeon chatted with teacher Caitlin Moles about efforts to help one child who uses a walker become more independent and to encourage another with speech difficulties to use words instead of letting others speak for her.

While the children played outside, Sturgeon went over the scores she’d given Moles and assistant teacher Lupe Morales on a classroom mental health climate rating.

“You always show that unconditional love and support, which is so important for not only typical kids but especially the ones who are struggling with different things,” said Sturgeon.

“I love how you’re just down there on their level, talking to them, striking up conversations.”

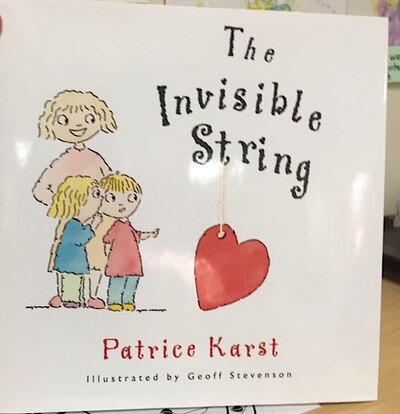

After that, Sturgeon stopped by a classroom that had just experienced a major loss—the unexpected death of a student at home over spring break. She’d helped the teachers navigate the delicate process of talking about death with preschoolers—providing books and leading conversations as the kids contemplated where their classmate had gone, what heaven was like and whether there were horses there.

Looking at the evidence

A small but growing body of research indicates that early childhood mental health consultants help both teachers and children.

There’s evidence that such services improve teachers’ classroom management skills while reducing negative interactions between staff and students, as well as job-related stress. For kids, consultation can speed up social skills development and reduce expulsions, which happen more often in preschools than the K-12 system.

Still, there are caveats.

Mary Louise Hemmeter, a professor of special education at Vanderbilt University, said variations in how consultants practice makes it unclear what exactly produces results.

“That’s why the research is probably not as strong,” she said.

For example, some consultants may focus on helping a teacher deal with one challenging child, more than supporting all staff members to develop their skills. It’s the latter that will make a bigger difference in the long run, said Hemmeter.

“The important task we have is to define what it is we deliver through mental health consultants,” she said.

Join Chalkbeat on May 24 for a keynote address and panel discussion on early childhood suspensions and expulsions. More details here.