State lawmakers from both political parties are seeking to undo a controversial State Board of Education decision that called for schools to test thousands of Colorado’s youngest students in English — a language they are still learning.

House Bill 1160 cleared its first legislative hurdle Monday with unanimous support from the House Education Committee.

The bill would allow school districts to decide whether to use tests in English or Spanish to gauge whether students in kindergarten through third grade enrolled in dual-language or bilingual programs have reading deficiencies.

The bill is sponsored in the House of Representatives by Reps. Millie Hamner, a Frisco Democrat, and Jim Wilson, a Salida Republican.

If the bill becomes law, it would overrule a decision by the State Board of Education last year that required testing such students at least once in English. That meant some schools would need to test students twice if they wanted to gauge reading skills in a student’s native language.

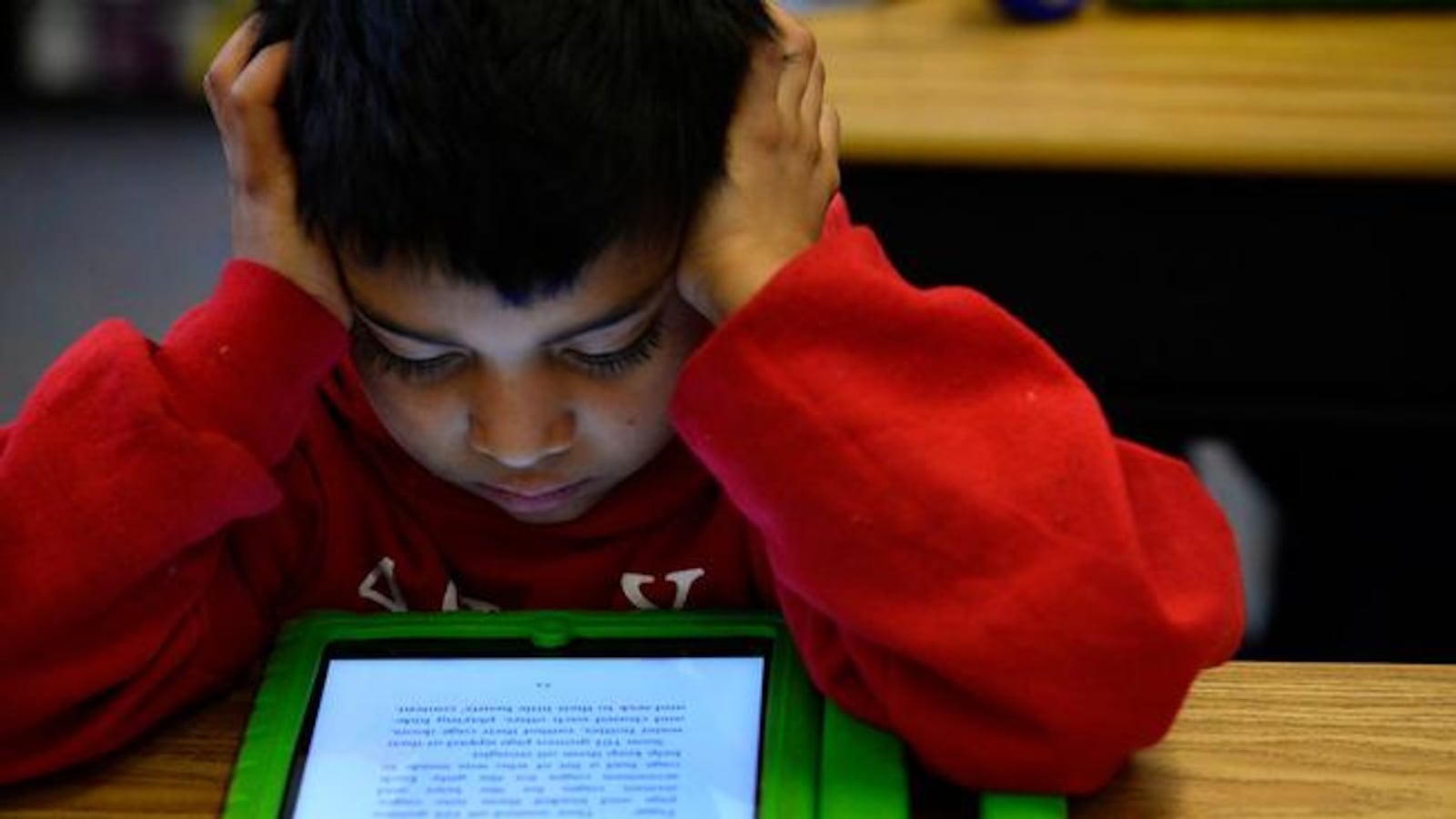

Colorado’s public schools under the 2012 READ Act are required to test students’ reading ability to identify students who aren’t likely to be reading at grade-level by third grade.

The bill is the latest political twist in a years-long effort to apply the READ Act in Colorado schools that serve a growing number of native Spanish-speakers.

School districts first raised concern about double-testing in 2014, one year after the law went into effect. The state Attorney General’s office issued an opinion affirming that the intent of the READ Act was to measure reading skills, not English proficiency. The state board then changed its policy to allow districts to choose which language to test students in and approved tests in both English and Spanish.

But a new configuration of the state board in 2016 added a new provision. If schools were going to test students in Spanish, they must also monitor students in English.

The board’s decision at the time was met with fierce opposition from school districts with large Spanish speaking populations — led by Denver Public Schools.

Lawmakers considered legislation to undo the board’s decision last year, but a committee in the Republican-controlled Senate killed it.

Capitol observers believe the bill is more likely to reach the governor’s desk this year after a change in leadership in the Senate.

Some members of the state board, at a meeting last week, reaffirmed their support for testing students in English.

Board member Val Flores, a Denver Democrat who opposed the rule change last year, said she opposes the bill. In explaining her reversal, Flores said she believes the bill would create a disincentive for schools, especially in Denver, to help Spanish-speakers learn English.

“If the district does not give the test in English, reading in English will not be taught,” she said.

Board member Steve Durham, a Colorado Springs Republican, said he still believes the intent of the READ Act was to measure how well students were reading in English.

“I think this is a serious departure from what the legislature intended initially,” he said last week. “The READ Act had everything to do with reading in English.”

Hamner, one of the sponsors of House Bill 1160, also sponsored the READ Act in 2012. She disagrees with Durham and told the House committee Monday that the intent was always for local school districts to decide which language was appropriate.

“We’re giving the local educators and districts the decision-making authority on what’s best for the students,” she said.

Multiple speakers on Monday said the requirement to test native Spanish speakers in English was a waste of time and money, and provided bad information to teachers.

“A teacher who teaches in Spanish will not be able to use data from an English assessment to drive their instruction, much like a hearing test would not give a doctor information about a patient’s broken arm,” said Emily Volkert, dean of instruction at Centennial Elementary School in Denver.

The bill only applies to students who are native Spanish speakers because the state has only approved tests that are in English and Spanish. Students whose native language is neither English nor Spanish would be tested in English until the state approves assessments in other languages.

“The question is can you read and how well,” said bill co-sponsor Wilson. “We’re trying to simplify that.”

Update: This post has been updated to clarify that schools may already choose to test students in English and Spanish. The State Board of Education did not strip that decision away but did add the requirement to that if students are tested in Spanish, they must also be monitored at least once in English.