Parents, students and staff at the Fisher Upper Academy on Detroit’s east side gathered at the school last fall for an exciting announcement:

The Ford Fund, the carmaker’s philanthropic arm, planned to spend $5 million on a new “resource and engagement center” inside the school.

Parents were thrilled to learn that they and their neighbors would soon have access to services like job training and a food bank in the same building where their children go to school, said parent Kenya Tubbs, whose 12-year-old daughter Camille is in 7th grade.

“The 48205 needs a lot of things,” Tubbs said of the high-poverty zip code where Fisher Upper is located. “A lot of people would not come to a community center if they need a job or if they need food, but they’ll come to a school.”

But three months after that joyful announcement, Fisher Upper was named to the list of 38 Michigan schools that state officials have targeted for closure because of years of low test scores.

Now, the effort to unite social services with education on the east side of Detroit has been thrown into question.

“We’re moving forward in the event that things are resolved at the state level,” said Ford Fund spokesman Todd Nissen. “But at the same time, we have to monitor what happens between the state and the district.”

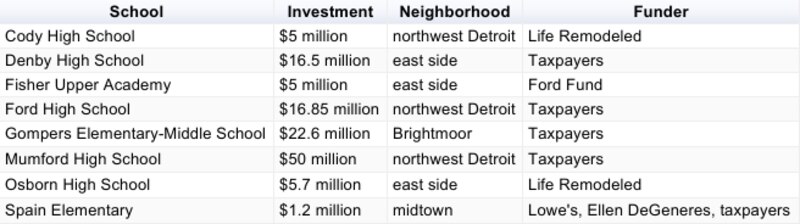

The turmoil at Fisher Upper is just one consequence of a school closure effort that’s focused largely on academics without much consideration for neighborhood impact or the loss of investment in schools. The closures could mean schools that have received tens of millions of dollars in recent years from taxpayers, corporate donors or community service organizations might soon be left vacant.

Among them is Mumford High School in northwest Detroit, which moved into a brand new $50 million building in 2012.

The new Mumford was paid for with $500.5 million in bond funds approved by voters in 2009. That money also built a new $22.6 million Gompers Elementary-Middle School in the Brightmoor neighborhood and paid for major improvements to Denby High School ($16.5 million) and Ford High School ($16.85 million).

All of those schools are on the closure list.

Also on the list are schools that benefited from major corporate and community investments such as Osborn High School. The Osborn building houses three small schools, all of which are on the closure list. It got a $5.7 million overhaul in 2015 from a Detroit-based nonprofit called Life Remodeled.

And other schools have been put on notice that they could be closed in 2018 if test scores don’t improve this year. Spain Elementary is on that list. It got a $1.2 million upgrade last year with help from a $500,000 check from Lowe’s that was delivered to the school on the Ellen DeGeneres Show.

The 38 schools targeted in 2017 — including 25 in Detroit — were identified for closure because they landed on the bottom five percent of state rankings for three years in a row.

The schools will be ordered to close in June unless officials from the state School Reform Office decide that closing them would represent a hardship to students.

Final decisions were expected to be made in the next few weeks but Gov. Rick Snyder announced Thursday that decisions likely won’t be made until May.

When they are made, they’ll be based on educational concerns — not buildings, said School Reform Officer Natasha Baker.

“The SRO is focused on our mission: to turn priority schools into the highest performing schools in the state,” Baker said in a statement. “We do this through academic accountability and have no statutory authority with the financing or operational components of schools.”

Advocates warn that closing a school impacts more than just students and teachers.

“These upgrades were done because the business community, the faith-based community and private individuals believe in these schools,” said Chris Lambert, the founder and CEO of Life Remodeled. “You’re rallying that kind of support and then you’re just going to chop it off? Cut off the limb? … How are funders going to trust that their commitments are going to be sustainable and fruitful in the future?”

Lambert’s organization raises money and recruits volunteers to renovate schools, parks and homes in Detroit neighborhoods. In addition to the major renovations at Osborn, Life Remodeled did an estimated $5 million in improvements to Cody High School, a three-school building with one school on the 2017 closure list and two on the possible 2018 list.

Lambert said he never would have raised the money or put years of effort into renovating those schools if he had any inkling that closures were looming.

“I asked at length,” he said. “We did hours and hours and hours of research into these schools, talking with DPS, funders, stakeholders, community leaders. We’ve got to make sure that we’re stewarding the donations … and using them wisely and all factors pointed to ‘These are schools to invest in.’ ”

But school closings were not expected until state lawmakers last year approved a $617 million financial rescue to keep the Detroit Public Schools out of bankruptcy. The new law included language requiring Baker’s office to close persistently low-ranking schools in the city.

The law specifies that the district (or the authorizer in the case of charter schools) “may not open a new school at the same location … within three years after the closure of the school unless the new school has substantially different leadership structure and substantially different curricular offerings than the previous school.”

Detroit school officials could, in theory, put new schools into closing buildings or move existing schools into them. But new schools would need to be approved by the School Reform Office and it’s not likely that the district would be ready to open new schools by September.

Some school buildings could be snapped up by charter schools if the district is willing to sell them but negotiations and sales could take months or years so Detroit — a city riddled with vacant and blighted buildings — could soon get some more. And that will cost money.

“Even a very brief period of vacancy is going to result in scrappers getting into buildings,” said John Grover, a Loveland Technologies staffer who last year authored a comprehensive report on school closings and vacancies in Detroit.

Grover’s report, called A School District in Crisis, found that the city had 82 vacant school buildings last year. Most had been stripped, damaged by fire and had become dangerous, blighted eyesores in city neighborhoods.

Past school closings by the Detroit Public Schools cost the district an estimated $100,000 per school in one-time “mothballing costs” such as securing the buildings, removing equipment and turning off water so pipes don’t freeze in the winter, Grover said. The district also spends roughly $50,000 per year per school to maintain and secure vacant buildings, he said.

“At the worst of times in 2012, they had so many [vacant school] buildings that they were monitoring all night long, they were out there playing a game of cat and mouse with the scrappers, going from one building to the next,” Grover said. “If you dump another 20 buildings into the school police department, that’s going to put a lot of strain on their resources … and they have a hard enough time dealing with active school buildings.”

It’s not clear who would cover the expense of securing vacant school buildings if they’re closed down by the state but the district, now called the Detroit Public Schools Community District, owns the buildings. Some of the schools including Mumford, Ford and Denby are currently part of the state-run Education Achievement Authority but they are scheduled to revert back to the district this summer.

Baker said the state has “made no decisions” about who will pay expenses related to closures. A spokeswoman for the district said city schools do not have the resources to shoulder those costs. “We would definitely need assistance,” she said.