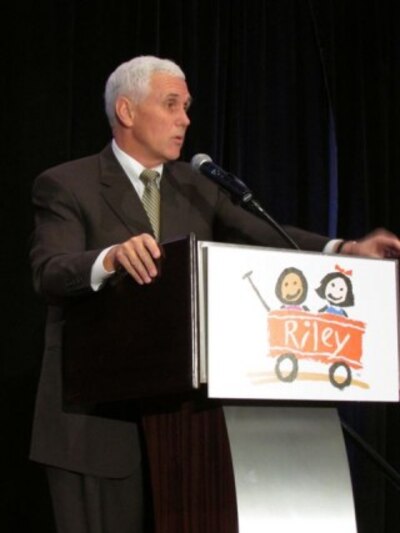

Since Republican Gov. Mike Pence and Democratic state Superintendent Glenda Ritz were elected just over a year ago, they’ve been at odds over how Indiana’s education system should be run.

But this fall, what was a sometimes awkward but generally polite disagreement has turned to open warfare.

The question is: Why?

The answer comes down to three fundamental divides that have thrown Pence and Ritz’s relationship into conflict: their very different beliefs about education, polarizing reactions to unexpected events, and irreconcilably opposite understandings of why voters elected Ritz in 2012.

The tensions have left education leaders, teachers and students across the state uncertain about what direction Indiana will head on critical issues like how schools are graded and how children will be taught.

At their core, Ritz and Pence disagree about education

Ritz is the only Democrat holding statewide office in strongly conservative Indiana, and her campaign platform directly opposed some of the favorite education ideas of Pence as well as Republicans who have set the agenda for years in the legislature and on the Indiana State Board Education.

Before running for office, Ritz was working as an elementary school librarian in Indianapolis’ Washington Township schools. She was president of her school district’s teachers union and had been a leader in 2011 of Indiana State Teachers Association’s opposition to private school vouchers.

Policies that Pence sees as justified accountability, Ritz has often viewed as unfairly punitive toward students and teachers.

For example, Pence supports school choice — private school vouchers and public charter schools — as a competitive force for positive change for traditional schools and an escape hatch for kids who want better options. Ritz, meanwhile, sees those programs as a drain on public dollars that could otherwise support student learning and pay teachers’ salaries.

Ritz decided to run against over her Republican predecessor, Tony Bennett, out of frustration with too much testing, especially a new third grade reading test that could be used to block low scorers from advancing to fourth grade. Pence, meanwhile, supports test-based accountability as a way to ensure that students have worked to master the material and teachers have effectively helped them learn.

In the wider picture, Pence generally adheres to typically Republican views on education that are shared among mostly conservative Indiana lawmakers. Ritz’s views are traditionally Democratic, a minority view in the Hoosier state.

Given such deep philosophical divides, it’s perhaps more surprising that Ritz has found any common ground with Pence and the Republicans at all. And indeed, early in her term, she did. But she has moved away from that approach — in part because of what’s happened since.

Events sowed distrust

In fact, after a few months on the job in early 2013, Ritz had won respect from some Republicans, including Pence, for working toward compromise.

Among those early victories, in January, Ritz made common cause with Pence by supporting a bill he pushed to more strongly connect business groups with vocational programs. In February, she struck a deal to hand off oversight of four Indianapolis schools in state takeover to Greg Ballard, Indianapolis’ Republican mayor, diminishing a divisive issue on which she and the state board stood far apart.

Republicans in the Senate even preferred her approach to evaluating Common Core standards over a different bill put forward by their Republican colleagues in the House.

Seeking compromise was a smart move, according to Republican political strategist Robert Vane, Ballard’s former press secretary who now runs his own public relations business. He compared her surprise election to that of his former boss in 2008, when Ballard upset Democrat Bart Peterson in the mayor’s race. Ballard, he said, immediately moved past bruising politics to governing on issues where he could collaborate with Democrats.

One big event in July seemed to derail that collaborative spirit.

That was the release of emails written in 2012 by Bennett and his staff. The emails led to complaints that Bennett tried to manipulate A to F grading for the benefit of a favored charter school — and the resulting controversy culminated in Bennett’s resignation as education commissioner in Florida.

The emails were obtained from Ritz’s office by journalists using state public records law, but Bennett’s allies blamed Ritz, whose staff released the emails in response to reporters’ requests. Later, even after a consultants’ review of A to F grading called Bennett’s changes to the formula “plausible,” he was hit with ethics charges, based on the emails, for using office resources to campaign.

The email controversy was quickly followed by moves by Pence and the board that Ritz objected to.

In August, Pence created the new Center for Education and Career Innovation, giving the state board a separate staff from the Ritz-led Department of Education. As Ritz and the board clashed over when to release A to F school grades, board members wrote a letter to Republican legislative leaders asking them to have the Legislative Service Agency calculate the grades. Ritz responded by suing the board, claiming it violated state transparency laws for deciding to send the letter outside of a board meeting.

Finally, there was last month’s board meeting, which Ritz abruptly ended rather than allow a vote that she thought could further limit her power.

Vane argues Ritz has herself to blame if she feels boxed in now. It seems likely, he said, that Ritz’s staff mined Bennett’s emails for embarrassing information, giving into a distracting obsession, he said.

“The Democrats who swept her into office, a lot of that was they just hated Tony Bennett,” he said. “They haven’t focused nearly as much on student scores as they have on settling political scores.”

But Kip Tew, an attorney and the former state Democratic Party chairman, said releasing the emails was simply the right thing to do.

“It was not politically stupid of her to do that,” he said. “It was showing the public what was wrong behind the scenes over the course of Tony Bennett’s reign as superintendent of public instruction.”

Tew suspects Republicans used the Bennett emails as an excuse to get more aggressive with her.

“I think the Republicans, since election night, were planning to marginalize her,” he said. “They smartly waited to do the marginalization until the legislature was out. They have all the power and ability to push her around. She basically stands alone at the statehouse.”

Different interpretations of Bennett’s 2012 defeat

The aggressive tactics employed by both sides since the summer are strongly driven by the disconnect in how each sees the results of last year’s election.

Republicans doubt Ritz can ever repeat her 2012 performance. They think she is a one-hit wonder.

If Pence and the Republicans really believe Ritz is a one-term problem and a politician who is all bark and no bite, then it makes some political sense that they would work around her to push their agenda, feeling no need to compromise.

“The big question for her politically is, was the Ritz coalition an anti-Bennett coalition or something more?” Vane said. “If he’s not on the ballot can she pull it off again? I think the odds are very much against it.”

But Ritz’s supporters often cite the fact that the 1.3 million votes she earned in 2012 were more than Pence or anyone else on the ballot attracted, suggesting she is a force to be reckoned with and perhaps even Pence’s equal.

If Ritz and her advisers believe they can garner anywhere close to the same number of votes again, then it makes sense that they publicly challenge Pence if they think he is trying to curb her power.

“Her victory was broad and deep,” Tew said. “The mandate was people wanted the reforms to stop. Her victory, and the size of it … I think the overall message of voters was slow this down.”

But how much political power came with Bennett’s defeat? Talk of Ritz as strong enough to be a potential challenger to Pence in 2016 may be overly optimistic, Tew said. But if Pence and his allies believe there is no consequence to bullying Ritz politically, they’re wrong, too.

“People who think she is a powerhouse overestimate her,” he said. “But people who think she can’t hurt them underestimate her.”

What happens next?

However they got here, Ritz and Pence now face the difficult tasks of extricating themselves from a battle that has brought them both increasing criticism. But how can they move forward?

The first step may be for each side to determine what it wants and how it can get there.

Ritz wants to be able to run the Indiana Department of Education without answering to Pence on matters that have always fallen under the state superintendent’s purview, like leading the process of setting academic standards and managing test data. She’d also like an honest debate on areas of disagreement, like what types of tests the state should administer and how to manage school choice.

Pence would like assurance that Ritz will faithfully execute Republican policies that pre-date her arrival or that have clear support from himself, legislative leaders and state board members. He might be willing to hear Ritz out on issues that she feels strongly about, but probably wouldn’t commit to much more than that.

“You have to understand how your personal philosophy meshes with political reality,” Vane said. “No one is saying she didn’t win or shouldn’t have a voice.”

But Democrats may not be ready to cede the point on whether Ritz holds enough power to force change. They might instead urge her to make a stand.

“Gather your army that put you in power and have them begin communicating with their legislators about the things they care about,” Tew said he’d tell Ritz. “Make sure the legislature knows she got elected, and these people are watching them. Reactivate the army and the grassroots to tell legislators if they mess with her and take away her power, they do it at their peril.”