A purple graduation gown casually hung against a wall in the front corner of Mandi Beutel’s second grade classroom at Chapelwood Elementary School, almost like an afterthought. Like she might’ve had it dry-cleaned and just forgot to take it home.

But this one, scavenged from Goodwill and strung up near her 1998 college diploma and honor cords, was there to set the tone for the first-year Wayne Township teacher’s classroom. Just like Beutel overcame obstacles to get to college and her dream career, she wants her kids to know they can, too.

“I want the kids to see what it looks like,” Beutel, 35, said. “It’s not for me, it’s for them, so they can see it, so it’s tangible. You can hold it, you can touch it, here you go.”

Beutel made the switch to teaching from a successful career in healthcare, and she had no qualms about leaving. Her school played no small role in her dedication to a job many might argue is harder to be in than ever: lately there have been complaints abound about inadequate pay, emphasis on high-stakes tests, and increasingly, challenges attracting new teachers to the profession and later, keeping them there.

Recruiting and retaining teachers are issues at the forefront for many schools across the state, as well as legislators and policymakers, as some school districts continue to report difficulty filling teaching jobs. Although the data on whether the state is seeing a true teacher shortage is inconclusive and doesn’t span every region or subject, it’s real for many Indiana educators.

But none of those things made Beutel think twice about going back to school to earn her license — and she credits Chapelwood’s many supports for new teachers for helping her feel stable and successful after just a scant few months on the job.

“I wanted to fulfill my purpose and my calling in life,” she said. “I left a career with a salary that I’ll probably never see again as a teacher, but every day I walk through these doors, there’s purpose and meaning in coming to work every day.”

A plan to support new teachers

Chapelwood’s first-year teachers are expected to hit the ground running once they’re hired over the summer, but they aren’t expected to do it without help.

Principal Heather Pierce said new teachers won’t know, in some cases, what grade they’ll teach until after they’ve gotten the job, so every second of planning time before school starts is precious. The school helps teachers get started writing grants for classroom materials and working with community partners to build class libraries and other stockpiles of supplies.

“Teaching is hard, I can remember my first year,” Pierce said. “It’s just a hard thing to go from theory straight into practice. There’s no in-between. You’ve got to be ready day one. Whatever program a teacher comes from, the expectation is so high, and we don’t have the flexibility of figuring it out.”

Veteran teachers are available to meet with new teachers and share tips and strategies for planning lessons and keeping their classes in order. The school tries to be open to whatever the teachers say they need help with and address as many needs as possible before kids come into the picture.

After the first few weeks, teachers have two years to participate in a program where they spend a total of 32 hours taking classes about acclimating to the job, said Shenia Suggs, an assistant superintendent in the district.

These are all intentional steps, Suggs said, to make sure new teachers don’t feel like they’re being cast out on their own while still motivating them to actively learn and grow as teachers. Leadership academies and other “cadres” split up by grade level and subject area with built-in mentors are other ways teachers can collaborate with their colleagues and find new ways to contribute in their school.

“It’s really, again, having the mentorship in place,” Suggs said. “And meeting the very specific needs as teachers tell us they need those and helping them through those processes.”

And interwoven in the discussions, plans, goal-setting, observations for evaluation and mentor sessions are chances for feedback, Pierce said. Beutel said she was surprised by the time her assistant principal took to help her understand what she could do better.

“He provided the kind of feedback that I want to give my students,” Beutel said. “He told me positive things and things I need to work on. I left his office feeling like I’m going to be a better teacher because of his support and his feedback.”

Finding someone to turn to for advice and help

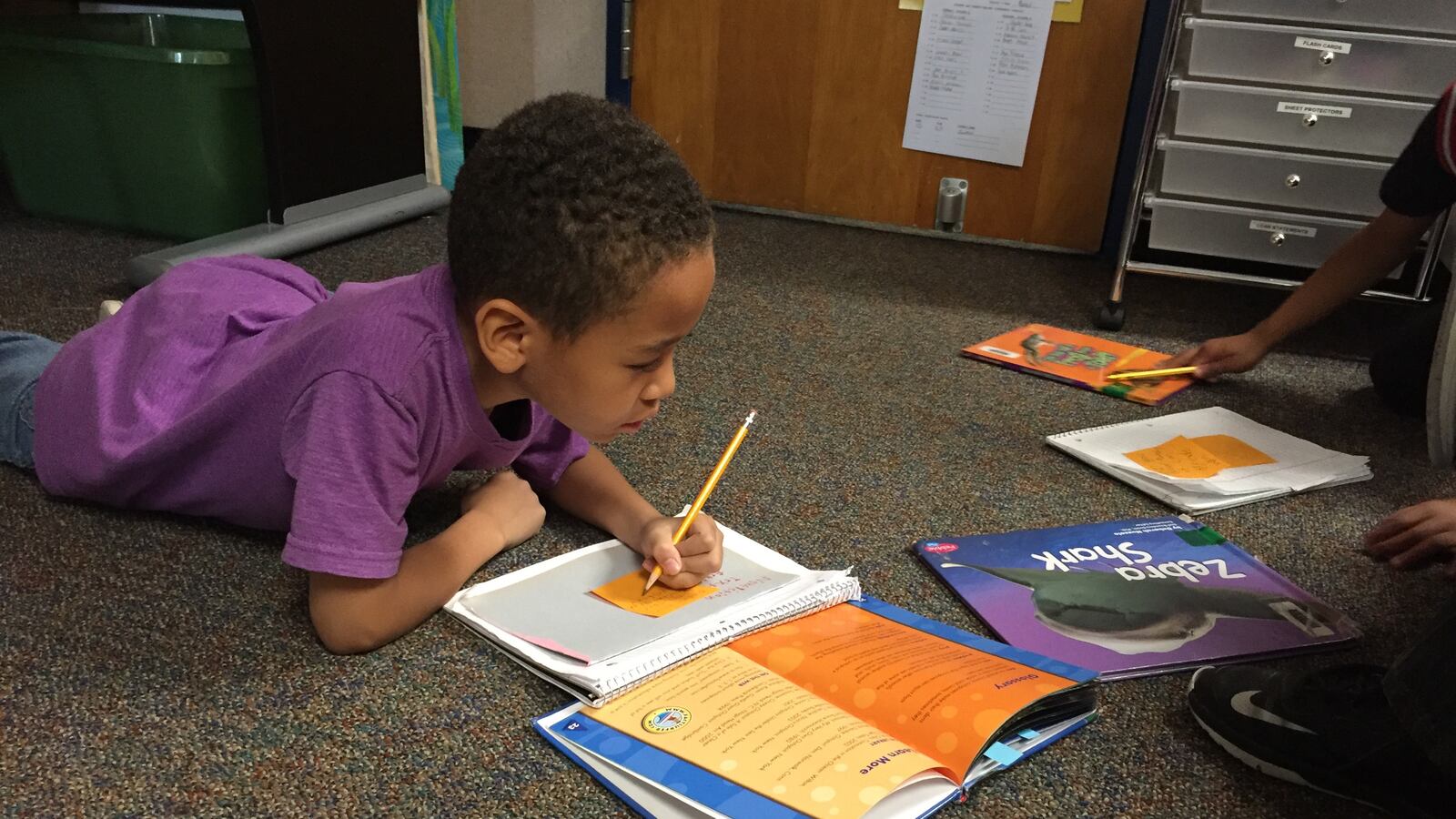

Beutel’s classroom is a lesson in organized chaos.

Kids were chattering at their desks after a lively song-and-dance session to review vowel sounds one morning earlier this month. But when she called out their tables (all named after colleges and universities), they quietly went to sit at the front of the room.

The tables with the squirmiest kids were the last to go.

“Waiting on one person,” Beutel called out. “Waiting on two people.”

About 30 minutes later, at precisely 10:44 a.m., Beutel had wrapped up her lesson, lined up the students and sent them off to a 10:45 a.m. music class. Her classroom management was more about method than attitude. As he lined up, one little boy ran up to Beutel and grabbed her around the waist in a quick hug.

But it took her work, and help, to get proficient at leading a classroom of children.

“I had a mentor in my student teaching,” Beutel said. “She was the best teacher I have ever been around in my entire life. I text her every day just asking her to help me. She’s on maternity leave right now, and she’s still helping me.”

Mentorship has already been highlighted, both nationally and in Indiana, as a critical way teachers say they can best help new teachers.

Indiana state Superintendent Glenda Ritz’s 49-member panel that is examining teacher retention and recruitment listed it as a top priority. Rep. Robert Behning, R-Indianapolis, also mentioned the merits of expanding such programs at an almost eight-hour legislative study committee meeting last week looking at whether the state is experiencing a teacher shortage and, if so, how to fix it.

Beutel looked to her building mentor, Nicole Caulfield, to help her tailor her math lessons for a kid who’s way ahead. He could add double- and triple-digit numbers in his head while she was teaching the rest of the class to add up numbers to get to 10. She said in college, she learned what to do for kids who were struggling, but there was less focus on those who needed more challenging work.

“I didn’t know how to differentiate for him to help him succeed,” Beutel said. “So Nicole and another coach came and met with me and showed me tools I could use to help him. He now gets his own customized packet for homework.”

That support, along with weekly team meetings, casual discussions and help developing new lessons, made Beutel’s first 10 weeks go more smoothly.

“(Caulfield) has been a blessing, that’s the only word I can use to describe her,” she said. “I know I can approach her and she’s not going to judge me.”

Keeping teachers happy so they stay put

Giving new teachers a good start is important, but sometimes a harder question for school districts to answer is how to keep their best talent from looking elsewhere.

Pierce said she knows much of the answer rests with her and other principals and the environments they create in their buildings.

At Chapelwood, Pierce said she hasn’t had a problem hiring, and she hasn’t noticed a decline in the quality of teacher applicants. Typically, she’ll see about 25 to 30 teachers applying for a position. Suggs said it helps that Wayne is located in a populated city where pay is fairly high — $41,112 for first-year teachers.

“I will say I think it’s because where we’re situated in the city, in an urban area, we’re near the airport,” Suggs said. “The level of candidates I think have been as good as they’ve always been. But I can see why in outlying areas that would be probably harder for them.”

Across the district, Suggs said she is still looking to find a teacher with a math, science, technology or engineering background who can take on special project-based courses.

“Those positions are going to be really hard to fill, and there’s not many candidates,” Suggs said. “Those numbers are real … we might not have 25 to 30 candidates in the future, and that’s a little concerning for me because here in the urban area we are competing with lots of school districts who are doing a lot of unique things.”

Districtwide, Wayne Township saw about 10 percent turnover among its teachers from last year, and just three left Chapelwood, Pierce said.

To combat poaching by other schools and districts, Pierce said Chapelwood has made great efforts to build a positive school culture — one where teachers feel like they have freedom in their classrooms, time to work with colleagues and opportunities to grow and move up the career ladder without having to leave the classroom and working directly with students.

“I think that’s what keeps people happy in their jobs and keeps them coming back, knowing they’re making a difference,” Pierce said. “They know they’re growing, and they know what they’re doing is appreciated, and I think if we can keep up with those things, I know we’ll keep them in the long run, I really do.”