Superintendent Lewis Ferebee has been worried about middle school students in Indianapolis Public Schools from almost the moment he arrived on the job in 2013.

Kids in grades 6-8 were scattered across the district — some in high schools, some in middle schools and some in elementary schools. And hardly any of them were passing state tests.

What he wanted then, he still wants now: a different approach to helping those kids learn. So does the school board.

But what’s the best solution? That’s the big question facing the district, and Ferebee thinks he’s closing in on at least one answer — get them out of high schools.

“Particularly where we have high schools that have middle grades … we really see some struggles,” he said when discussing newly released ISTEP scores. “I don’t think our middle grade students are being served well in that configuration.”

In fact, it’s hard to overstate how bad the situation is. About three out of four IPS students in grades 6-8 failed ISTEP last year. Middle school is also when IPS begins to lose student to competition. Hundreds of students leave IPS entirely during the middle school years.

Ferebee has a fix in mind: reconfigure middle school grades to move pre-teens out of the combined middle and high school buildings and into schools that serve grades K-8 and possibly middle schools.

A lot of research supports the plan. Even so, reconfiguring schools alone may not be enough to solve the problem of low middle-grade test scores.

The middle school conundrum

There are legitimate biological reasons why middle school students bring special challenges. The physical changes kids go through in those years are often accompanied by emotional shifts, which can lead to behavior problems or difficulty focusing on school work.

It’s not just IPS that faces this problem. Middle schools are a puzzle for nearly every type of school district.

Across Indiana, middle school students have unusually low ISTEP scores with an average passing rate about 7 percentage points below elementary students last year. Test scores were particularly low in 2015, when Indiana introduced new standards and scores plunged across the state. But the middle school test score gap has existed for years.

Part of the problem is that middle school students generally don’t get the social support that kids get in elementary school, but they also don’t yet have the maturity to effectively manage their academic work, which most students become better at in high school, said Ryan Steuer, who taught middle school English and launched a project-based learning community in Decatur Middle School.

“They’re in a weird, awkward phase and they need a lot of help,” he said.

In IPS, middle school students score very poorly, but they actually aren’t any farther behind in how they compare to their elementary school peers than in the rest of the state.

The passing rates for IPS middle school students lags behind the district’s elementary school passing rate by about 7 percentage points, exactly the same gap as the state averages.

What’s different is that the average scores for all schools in IPS, along with other high-poverty districts and schools in cities with lots of barriers to learning, are unusually low compared to other types of public schools. Still, the results are stark — just 24 percent of IPS middle school kids passed both the math and English ISTEP tests. Statewide about 49 percent of middle school kids passed ISTEP.

The passing rates are extraordinarily low at the most troubled schools. Less than 10 percent of middle school students passed ISTEP at seven IPS schools. Most of the worst test scores are at combined middle and high schools, where kids in grades 6-8 share a building with older students.

There are eight of those combined schools in IPS, and none of them did better than the district average for middle school students.

“The data has shown that them being in those buildings has not been successful,” said Wanda Legrand, deputy superintendent for academics. “Our goal now is to create the best situation for children based on data.”

IPS is also losing kids during the middle school years, to competing options such as charter schools, private schools — sometimes thanks to state-funded tuition vouchers — other districts or possibly even dropping out.

For a district that depends on robust enrollment as the basis for per-student state aid, there are also financial reasons to try to persuade kids not to choose other options or give up on school. And middle school grades are a period when many kids disappear.

Consider the class of IPS students who moved from sixth to seventh grade last school year. At most grades, a class of students varies a little bit from year to year. But it appears an unusually small proportion of kids stuck around for seventh grade last year at IPS schools. The district last year had about 1,907 seventh graders. But the class was 24 percent smaller than the prior year’s sixth grade class, which had 2,499 students.

Last year, nearly 2,700 IPS middle school students went to 6-12 or 7-12 schools. Almost exactly the same number of IPS middle school kids were at elementary schools. Close to 150 students went to Key Learning Community, a K-12 school that will close next year. The district’s only middle school Harshman Middle School, has about 600 students. (Emma Donnan, a former IPS middle schools is now run independently by Charter Schools USA after state takeover in 2012, so its enrollment is not counted as part of IPS.)

Teaching matters

IPS plans to move most middle school students to elementary schools, and it may also add middle schools, in hopes that students do better academically. The district is planning public forums this spring and aims to begin the conversion in 2017-18.

But a question remains: will simply keeping kids in elementary schools longer or creating new middle schools make the difference? Some experts say only if there are also changes to the way students are taught.

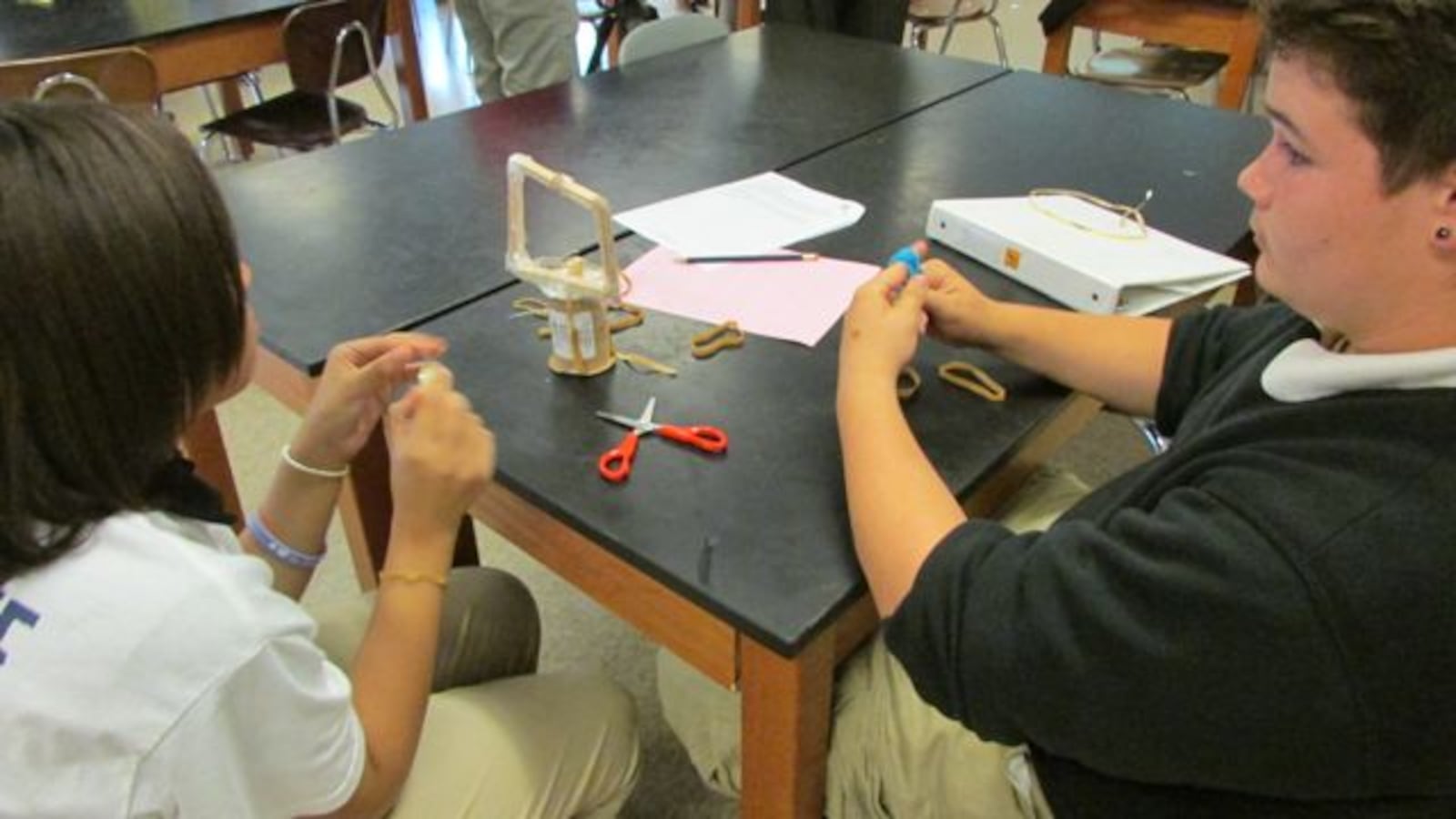

“If you can create an environment that would be conducive to the creating of culture specifically for middle school, then I think that that could be beneficial as a practical step,” said Steuer, who now leads Magnify Learning, a non-profit that trains teachers to use project-based learning. “But the teaching methods also have to change.”

As a teacher in Decatur, Steuer helped create a school-within-a-school that dramatically boosted test scores in middle school grades, he said. And when Magnify works with teachers in combined middle and high schools, they try to create groups of educators who focus on middle students.

It’s harder to offer spaces designed for each age group when many grades are in one building, said Marcus Robinson, CEO of the Tindley Accelerated Schools, an Indianapolis-based charter school network. But schools can create a customized experience for kids even if they share buildings.

Tindley began growing rapidly in 2012, launching two middle schools and three elementary schools. But for most of its history, it ran a single combined middle and high school, much like those common to IPS. Tindley students scored well on state tests because the school had a completely separate and very structured program for middle school students, Robinson said.

“Those kids need things that are categorically different,” he said, “both for their emotional development as well as for their academic achievement.”

The value of rearranging kids

There’s some pretty strong evidence IPS is on the right track. Rearranging kids might, indeed, help with achievement, especially if it’s paired with good teaching methods, some of the latest research shows.

When Harvard professor Martin West saw a study showing that in New York City middle school age students who attended elementary schools scored much higher on standardized tests than students who went to middle schools, he was skeptical.

“We know that what matters really is the quality of teaching,” he said.

So West and a colleague decided to do their own study comparing students who went to middle schools to those who went to combined middle and elementary schools. They looked at several years of test scores from students across Florida. The results, he said, were stunning.

Students who went to combined elementary-middle schools learned significantly more than students at middle schools. When students transitioned to middle school, their test scores suggested they lost the equivalent of up to seven months of learning in the first year.

All transitions can be hard on students, said West, but the move to middle school from elementary school appeared to be significantly more difficult than the move to high school from middle school.

Even worse, there was no catching up. Students fell further behind for every year they were in middle school. Then, when they entered high school, Florida students who’d attended middle school came in behind their peers who stayed in elementary school.

“On average students tend to learn less while they’re enrolled in middle school,” said West. “Stand alone middle schools appear to be very difficult to run well.”

The future of middle grades

Even with the IPS plan still being developed, middle school students already are shifting away from combined middle and high schools.

Last fall, IPS removed middle school grades from Shortridge High School as part of a wider overhaul of magnet programs at several schools. And it announced plans to phase out middle school grades at Broad Ripple High School, an arts magnet.

The district also plans to expand the arts magnet elementary school to eighth grade and launch an additional Center for Inquiry magnet school, which will serve students in grade K-8.

But Ferebee said other changes, including opening new standalone middle schools, are still open to discussion.

The district already has plans to provide a building for an experimental, charter middle school being developed by Sheila Dollaske, a former-IPS principal and Mind Trust fellow.

Legrand said decisions will be designed to improve outcomes for children in middle school grades, whatever the setting.

“We want to make sure we invest in staffing appropriately and providing the resources and the professional development so that it’s a true middle years program,” said Legrande. “It has to be designed specifically for that adolescent child that’s in the middle.”