As the country nears the end of an another week of violence that has again propelled issues of race and justice to the forefront, educators are grappling with how to make sure schools are “culturally responsive.”

Last week, Alton Sterling, of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile, of St. Paul, Minnesota, both black men, were killed by police officers. At the heels of those shootings was another in Dallas, Texas, where multiple police officers were killed or wounded.

But Jamyce Banks, an Indianapolis consultant who’s worked with districts across the state on how schools should tackle conversations about race and culture, said educators shouldn’t wait for a crisis.

“Culture encompasses many things other than race, and we don’t have conversations until there is a conflict,” said Banks, the founder and CEO of the Whatever It Takes consulting firm. “When the house is burning down, pouring water on it is nice, but the house is still burning.”

Banks, along with Nathaniel Turner, author of “Raising Supaman” and Brandon Cosby, the executive director of the Flanner House community organization, will be speaking on a panel about culturally responsive schools at the Indiana Black Expo’s education conference next week.

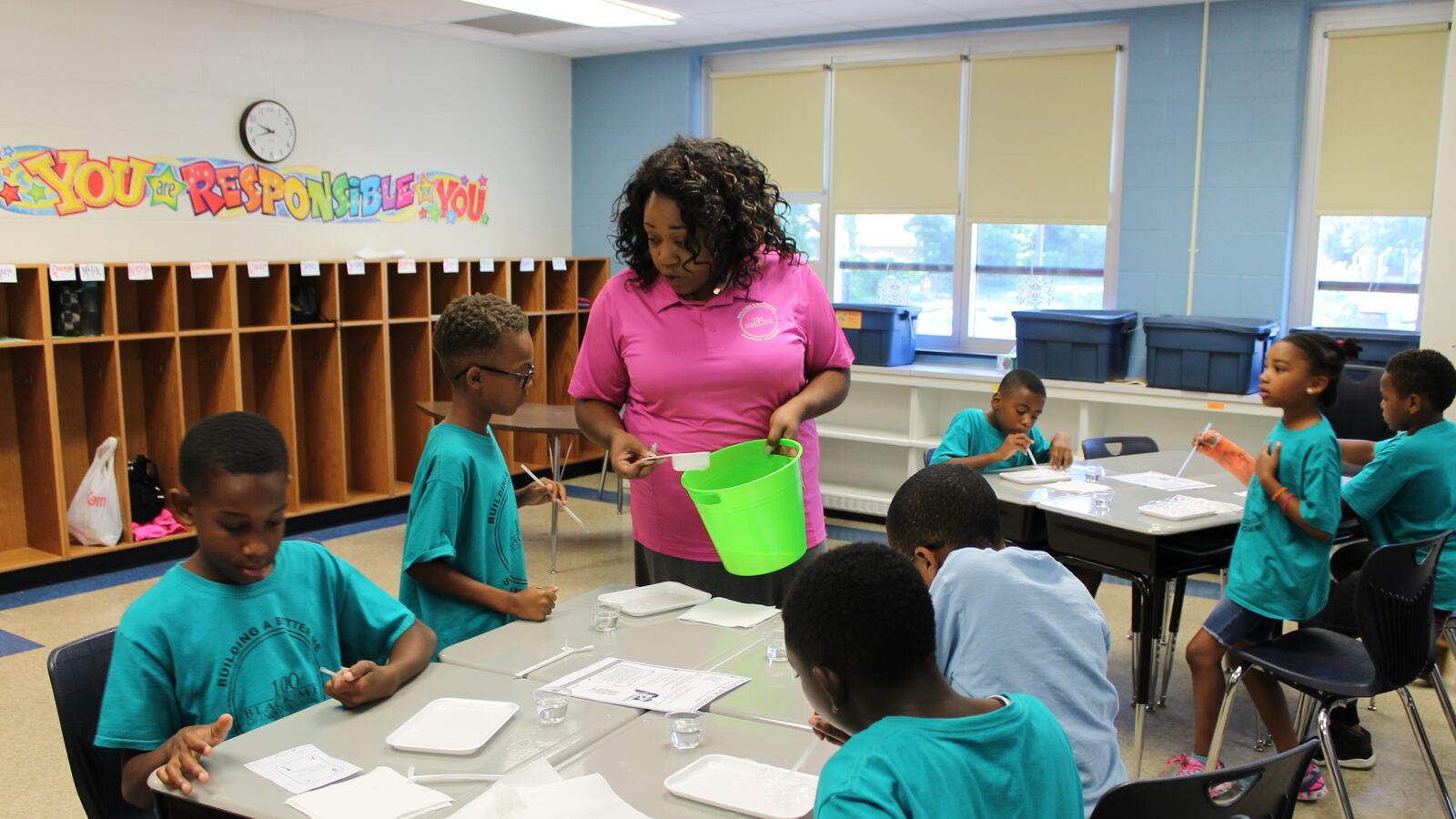

But when crises do happen, kids need to talk about them. The students turning up for class at the summer academy run by 100 Black Men of Indianapolis at IPS School 74 on the near eastside were full of questions today that they wanted answered. Their teachers tried to respond as well as they could.

“We have to meet their most basic needs before we can educate them,” said Jagga Rent, the director of the summer academy and dean of students at Hamilton Southeastern High School. “These events affect them emotionally.”

The topic of the academy’s usual Friday meeting this morning was very timely, Rent said. It was about effective communication.

“We talked about when you’re angry, how to communicate and how to do that effectively,” Rent said. “It’s important to know how when you’re angry and you don’t communicate effectively, bad things happen.”

But anger was only one of the thing students were feeling today.

“I’m disgusted and upset, but overall I’m kind of frightened,” said Aeriyae Johnson, who will be a 10th-grader at Fishers High School this fall. “I have three little brothers and they are asking all these questions and we don’t have answers.”

Rent emphasized the importance of educators allowing students to express themselves and to share how they’re feeling. This sentiment was echoed by Kendale Adams, an Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department officer and member of 100 Black Men of Indianapolis who works with the academy.

“Let’s put the textbook down. Put the curriculum down and just talk,” Adams said. “Let kids express themselves. Give kids that option.”

Johnson said in her experience during the school year, many of her teachers are “careful” about what they say, but that isn’t what she wanted from the adults and educators in charge of guiding her.

“We need security. And not like security guards, but a safe space to know we can express ourselves safely and not offend anyone,” Johnson said.

Her friend, Zanobia Young, who will be a 10th-grader at Providence Cristo Rey High School and also volunteers at the academy, said many of her friends didn’t feel like they could express themselves or do anything about the situation.

“We all have different emotions. The black boys at my school especially get mad,” Young said. “I feel upset and frustrated, there’s nothing we can do about it. I don’t think we’re going to get justice because we didn’t get justice for Trayvon Martin or Michael Brown.”

Schools play an important role in fostering conversations around race and culture, said Banks, who trains educators to more effectively address race in the classroom.

When Banks works with a school district — so far she’s worked with Lawrence and Wayne townships in Marion County, The New Teacher Project at Marian University, as well as mayor-sponsored charter schools and schools in northern Illinois — she starts by having everyone involved in the training take a “cultural intelligence assessment,” which encourages educators to reflect on their work and what they could do better.

To do that, Banks said, school and district leaders, as well as classroom teachers, need to have transparent conversations and realize their own limitations. Many teachers in Indianapolis classrooms have not had the same experiences as their students, regardless of race, she said.

In Indianapolis, most districts are gaining black, Hispanic and other minority students, while teachers remain mostly white. Teachers need to be prepared to talk about cultural differences with students throughout their lessons, she said, and some of that responsibility rests with teacher preparation programs to make sure educators are equipped to bridge cultural divides.

“It opens up neutral ground,” Banks said. “Generally speaking, if you say to people we’re going to do a diversity training … people become alarmed. Everyone is taking the assessment and everyone is looking at individual scores in the context of how do I become better at what I do, not about one particular situation or person.”

Turner, one of the panel member’s whose book includes letters he’s written his son throughout his life and parenting advice, said parents also shouldn’t necessarily wait for schools to tackle issues of race and violence.

“We can talk to kids until we are blue in the face, but kids watch us, kids learn from us,” Turner said. “I believe the impetus always has to be on parents and adults to set the benchmark for how children behave.”