Last in a Chalkbeat series about virtual schools.

Teacher Kris Phillips sat in her sunny office on a recent fall afternoon, preparing to start a math lesson for her middle-schoolers who needed extra help with fractions.

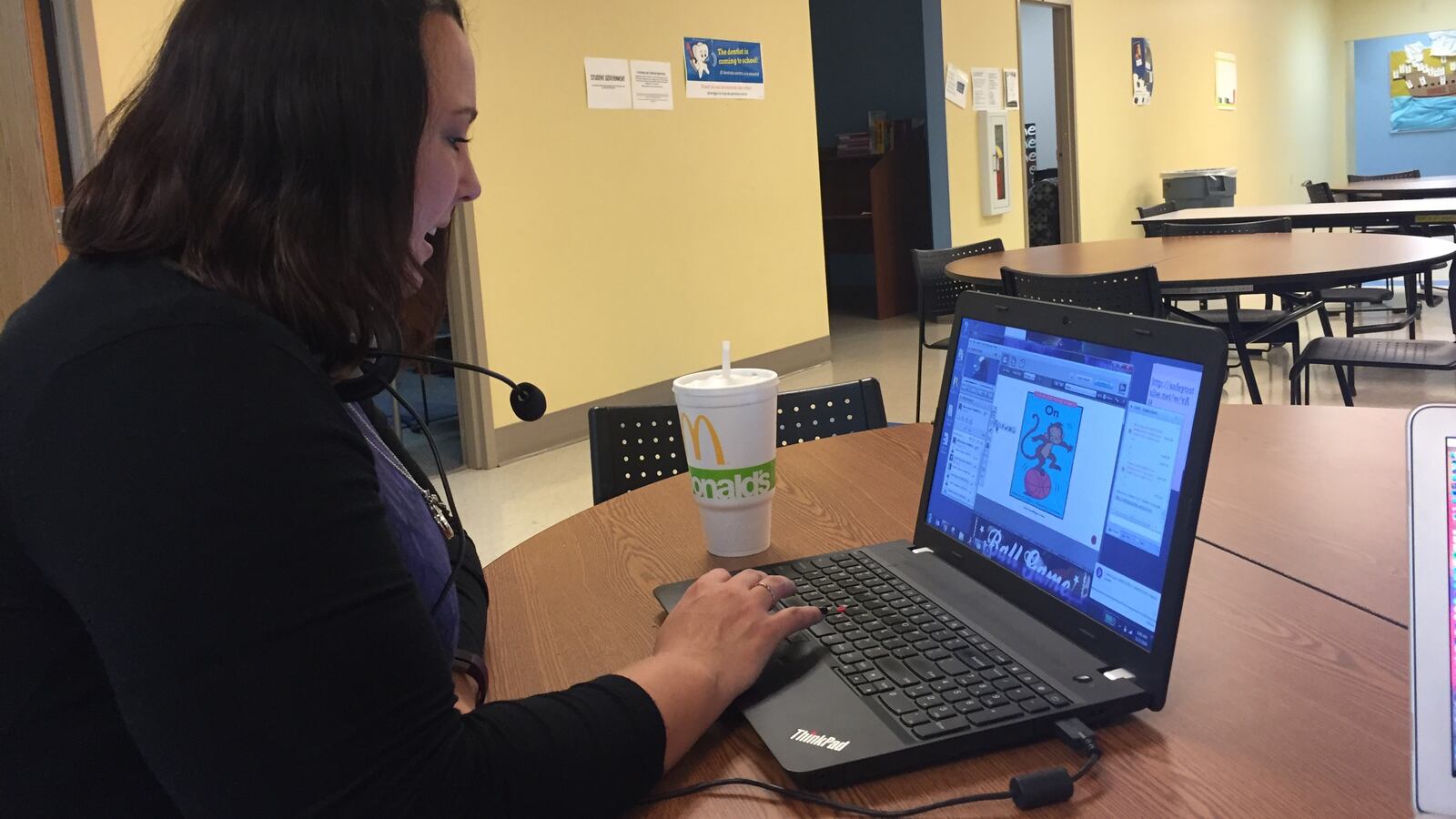

But unlike most teachers, she first carefully donned a headset and microphone.

That’s because Phillips’ classroom isn’t surrounded by the brick walls of a school building. Rather, she teaches within the confines of a computer screen, serving students who could be listening to her from every corner of the state.

Phillips is in her third year of teaching at Hoosier Academies, the largest virtual charter network in Indiana that serves about 4,200 kids across three schools. She’s the kind of teacher who’s willing to do just about anything to engage her students — even if that means getting a little goofy.

The former Avon educator knows it can be difficult to get kids, particularly those who struggle academically or who lack support at home, to connect with her and her instruction via computer, so a sense of humor and a bit of entertainment can go a long way.

The goal of the day’s lesson was simple: Phillips wanted to shore up her students’ skills in multiplying and reducing fractions, and she used a popular computer game called Minecraft and a dating game that included a character created by one of the girls in the class: A larger-than-life sheep named “Sheep, O Honorable Sheep.”

“I try to tap into their interest and make it fun or exciting,” Phillips said. “And if I have to be goofy in the process, I don’t care.”

The game and props proved fairly effective. Responses from her students, who she could hear through her headphones, flew up quickly on the screen in a small chat box as she asked them how to multiply pairs of numbers or reduce fractions. The set-up resembled a slightly complex Powerpoint presentation, with the lesson housed in a larger central screen surrounded by other boxes containing tools, chat rooms and buttons linking her to individual students’ workspaces.

When she later split students into individual spaces so they could complete extra problems and interact with her one-on-one, there was none of the transition chatter you’d commonly hear in a traditional classroom, so things moved more quickly. She moved through the spaces like you’d switch tabs in an internet browser. A single click took her from the main lesson presentation to other screens where she could see their individual work.

Her schedule can fluctuate from week to week, but when she’s not teaching one of her three or four live lessons a day, she’s analyzing student test data, meeting with parents or students or creating progress reports.

Phillips and other educators who spoke to Chalkbeat about their experiences teaching in online schools were adamant that this setting — where the four walls of a classroom are replaced by online chats, lots of emails and video screens — was best not just for their students, but for them as teachers.

Although as a whole, online schools across the state have failed to demonstrate widespread academic achievement, they remain a choice that a growing number of Indiana students and students across the country are turning to.

Teachers and educators in online schools shared why they chose virtual schools, the challenges they can face educating students and the success stories that keep them going.

Excerpts from interviews have been edited for length and clarity. Editor’s notes are in italics.

What makes their jobs different from teachers in traditional schools?

Kris Phillips, middle school math teacher at Hoosier Academy: It’s really a lot of parallel between the brick-and-mortar and virtual — it’s just we’re doing it on a different platform.

Ann Semon, sixth grade teacher at Hoosier Academy: At traditional schools, I spent my whole time managing behavior and kids getting in fights. I wanted to give them everything, but I felt like I couldn’t, whether it’s because there weren’t enough resources for someone to help me in my classroom or kids speaking multiple languages and I couldn’t help. I just felt like I couldn’t be successful.

Alyssa Davis, kindergarten teacher at Hoosier Academy: The caseload is certainly larger in our setting, but the beauty of it is I can pull these small groups while the rest of their class is working at home with their learning coach. Whereas in a brick-and-mortar school, the classroom management is hard.

This is nice because they are there with a learning coach doing lessons throughout the day, and I am there for lessons.

(Students in virtual schools have designated learning coaches, who can be parents, guardians or other engaged adults, who help them manage their classwork and communicate with teachers. The coaches are especially necessary in younger grades and usually will become less engaged day-to-day as students get older and can be more responsible for themselves. Indiana’s virtual school classes can enroll upwards of 50 students at a time.

But for most Indiana students in online schools, the flexibility and lack of teacher oversight aren’t working. Virtual schools see high rates of student turnover from year to year. At Hoosier Academies, for example, more than half of students turn over each year.)

What they like best about teaching in a virtual school

Corrie Barnett, middle school math teacher at Hoosier Academy: I loved this year because of the one-on-one attention. Each of my 50 students, I get to see them every day. Something we required for students this year was live class (lessons) for the first time. It’s just been amazing to see the growth. It’s just made us feel a lot more tied into (students’) families.

(Live lessons — similar to Phillips’ fraction-themed dating game lesson above — are online versions of a typical class lecture, where teachers present information to students and can work with them in groups or individually on the material. While teachers at Hoosier Academy have offered live lessons in the past, Barnett explained that students now are expected to attend.)

Phillips: One of the things I love about virtual teaching is that you don’t have to worry about the whole classroom management aspect of it. I feel like I can put my energy into teaching, and I can really focus on them learning. I don’t have to worry so much about the transition through the hallways, and the disruptions in the classroom and the things like that that you would normally.

What they find challenging about teaching in a virtual school

Davis: Parents are really part of the team. That is our challenge — making sure that our families are working at home. That is part of our job that is unique, too. We are not providing instruction all eight hours of the day. I do take time out of every day to make sure they are logging in and completing courses. But our job very much is teaching our students and guiding their learning coaches and families at home through our program.

Phillips: Coming in as a new teacher, it takes a little while to learn everything. But we have a really great system in place for training. I’ve been at four different school districts now, and I have never gotten as much training as I have at this place. They literally give you so many tools to learn from. But it does take a little bit to catch up on it in the beginning because there’s a lot of different platforms and technology that you have to learn.

Why do you think the performance of virtual schools isn’t better?

Phillips: We’re doing what we can with what we have. We have some kids that came to us that were below grade level, and we’re just trying to pull them up.

I had a kid a few weeks ago, and I heard on my microphone that it was noisy. She confided in me that she was in a hotel room because she was homeless. I immediately referred her to our (Family Academic Support Team). They get them resources. They find organizations in the area to help them get what they need to get on their feet. If we have students who aren’t showing up in class, maybe something like that is going on at home, and so we need to be aware.

Byron Ernest, Head of Hoosier Academies: When online education came into being, I think everybody thought, “You know what? The only people who will want to do this are ones that are super high-flyers.” And I think it didn’t take long for folks to realize, you will get those kids, but you’re also going to get students from all places, just like you would from any school.

Nobody was really prepared for that piece of how it was going to look. I think for the here and now, we realized, the teacher matters a lot in this. And I think that was a piece that maybe in the very beginning for all online education, that was maybe a piece that wasn’t there.

The other piece is really making sure that operationally, it still has to be a real school. Everything that goes on in any other school has to go on in an online school as well.

Derek Eaton, principal of Achieve Virtual Education Academy in Wayne Township: The majority of our 200 students, most are high school age, but of those in the seniors group, 18-19 year-olds, is our largest group of students.

And we’ve got quite a few adults, and they don’t want a GED. As long they don’t have a high school diploma we can take them. Now, adults tend to struggle the most. They get out of school mode, and what we see is life gets in the way. Up front they think (online school) is great, but they don’t consider themselves high school students — but we operate that way. You need to realize you are enrolling in high school again.

Melissa Brown, principal at Indiana Connections Academy: We get students where some are like, this is a last ditch effort for them. It’s really, really hard sometimes to make progress with those kids who just stay for a little while. So we have some really targeted efforts around engaging kids and keeping them here.

I will say first and foremost that our (English) scores are good. I’m very proud of that, but it also makes a lot of sense. Our students are probably reading more just by virtue of being in our school. I know our students are scoring lower than the state average in math, and it makes sense to me. Math is harder to learn online for a variety of reasons, but I think that daily instruction piece (is key). We need to get more to a model where students are doing daily math instruction.

That said, our math scores are trending up. While we’re not there yet at the state average, we’re getting there with a 2 percent increase every school year. It doesn’t seem like a lot, but it’s progress.

Now would I like for us to be an A school? Absolutely. You will never see me stop trying for an A, and I’m just that kind of person. But the truth is we have students who struggle. I know that answer sounds like an excuse, but these are students for whom nothing has worked before.