Getting kids to school can be hard: They miss the bus. Their families are evicted. They have dentist appointments.

Some days it’s trivial issues that keep kids home. Other times it’s steeper challenges. But a growing body of research shows that when students are chronically absent from school, they are much more likely to face problems with everything from learning to read to graduating high school. That’s why Indianapolis Public Schools is investing in a new program aimed at boosting attendance at schools across the district.

School districts across the country are paying extra attention to improving attendance and reducing chronic absenteeism in recent years. Indiana is one of many states that now requires schools to track chronic absence, and districts from Grand Rapids, Michigan, to Milwaukee are tackling the challenge of tracking and reducing absences.

In Indianapolis, the effort started in 2015-2016, and it ranges from rewards for kids who have perfect attendance to targeted help for students who miss 18 days of school or more. It’s being rolled out with the help of eight new graduation counselors, who are tasked with making sure struggling students don’t fall through the cracks.

“People want to spend a lot of time talking about more in-depth strategies for reading, literacy,” said Lisa Brenner, who runs student services for the district. “But all your strategies don’t work if the students aren’t there.”

At School 83, a neighborhood elementary school on the northeast side, staff have been spending a lot more time talking about attendance over the last year and a half.

The school sends students home with flyers about attendance, and when parents come in for conferences with teachers they talk about how important it is for kids to show up. When social worker Kim Winkel hears from parents, she always checks on their children’s attendance and tardiness.

“I see them slowly getting it,” Winkel said. “The families and the parents are starting to see and buy into us saying, ‘you need to be here. You need to be learning.’ ”

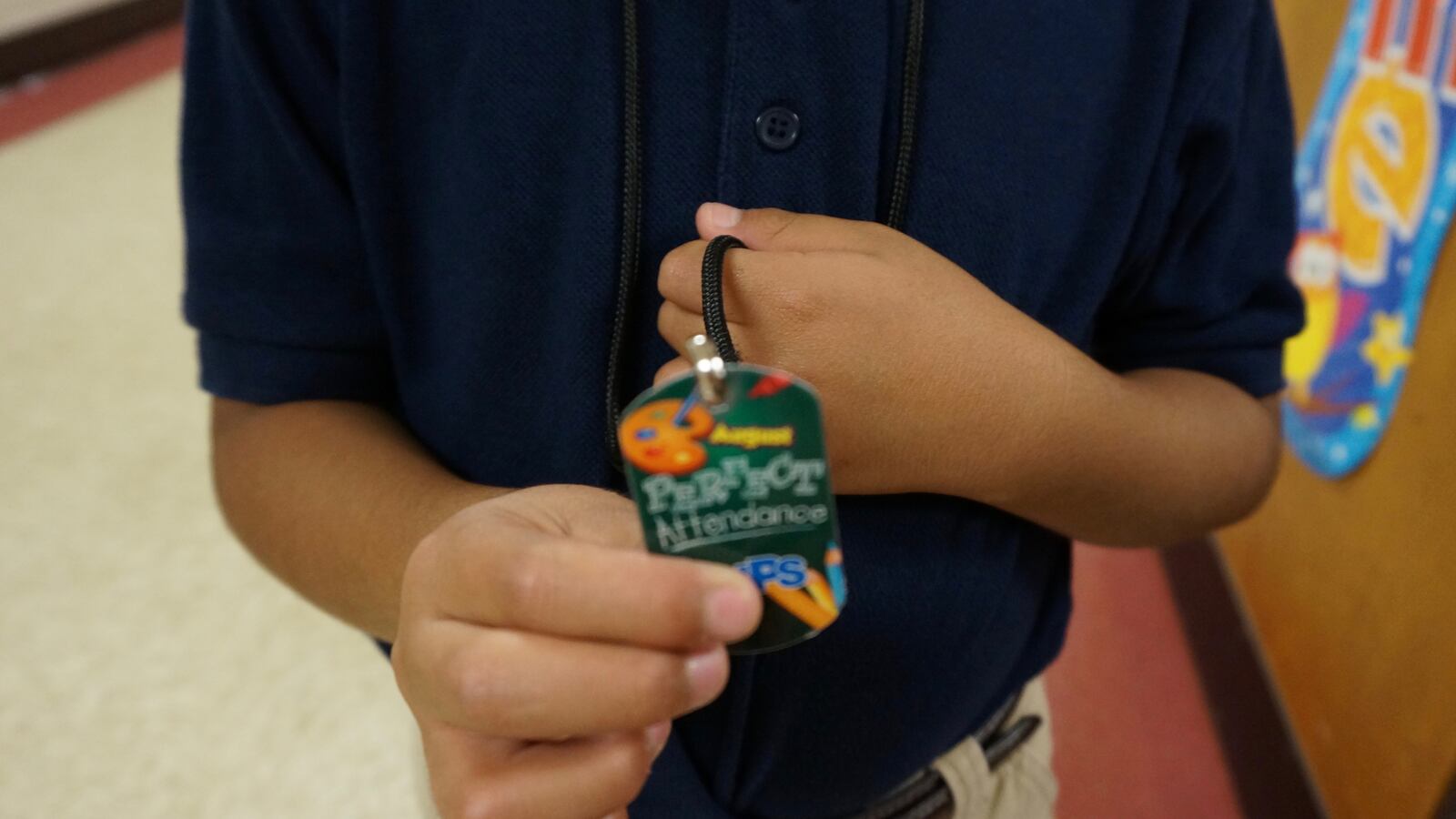

School 83 is also offering a slew of rewards for kids to come to school: There’s a club for students with good attendance, students can earn snacks or the chance to wear jeans and the class with the best attendance each month has a party.

Those are the kind of small programs designed to reach all the kids in a school, said Hedy Chang of Attendance Works, a national nonprofit that researches and promotes school attendance. School-wide efforts like rewards are often the first step in district strategies to improve attendance, and they are most effective with students who only have minor attendance problems, Chang said. Reaching kids with more severe attendance gaps is a different challenge.

“You have to start some place where you feel like you can make a difference. Messaging just doesn’t take that much,” Chang said. “It’s harder to move the kids out of chronic absence.”

So far, the district has seen relatively modest impact on students with severe attendance issues. District data show that the number of students who were chronically absent — those who missed 18 or more days of school — fell by 232 students in the first year of the program. Last year, 9.55 percent of students were chronically absent, down from 10.14 percent in 2014-2015.

Absence rates are typically much higher in IPS high schools than elementary schools. At most elementary schools in the district, fewer than 5 percent of students are chronically absent. At some of the district’s high schools, however, chronic absence rates are as high as 35 percent, according to state data.

Districtwide, the improvement has been faster among students who are on the cusp, missing 10-18 days of school. During the first year of the effort, the number of students at-risk fell from 16.93 percent to 14.45 percent — 808 fewer students fell into that category.

But the district is also in the beginning stages of the program. This year, staff are focusing on reaching kids with more severe attendance issues, Brenner said. That means creating programs that get kids excited about school like adult mentors who eat breakfast with students. And it means offering targeted help based on the problems each student is facing.

“There are lots of great things we could do,” Brenner said, “but if they are not meeting the individual needs of the students, they are just not going to be effective.”

Staff at School 83 are already spending a lot of time working directly with families when kids struggle to come to school. When kids miss school, they call parents to check in. If that doesn’t work, they stop by students’ houses. And they try to help families find a plan to get their children to school.

Last year, a first grader was so anxious about coming to school that she would cry every day and complain of stomach aches, said Cathy Pullings, the parent involvement educator. Eventually, the girl’s mother started making excuses to keep her home.

So Pullings made a deal with the student — come to school, stay all day and at the end of the week, she would visit Pullings for a special prize.

“Before I knew … she didn’t have to come and get that prize anymore. She was there every single day,” Pullings said. “I think it’s just a little push to say, ‘I’m here for you. What can we do to make it better for you to come to school?”

All this work seems to be paying off. School 83 has one of the lowest rates of chronic absenteeism in the district. Last year, the school, which enrolled 290 kids, had just 3 students who missed enough school to land on that list.

Staff have always paid attention to average daily attendance at School 83. But the new program was an extra reminder to focus on what was going on with every student, said principal Heather Haskett. They are constantly looking at data to make sure students aren’t falling through the cracks.

“Now, we’re more direct and more explicit about what we are doing,” she said. “We are really looking at every single, individual child and monitoring their attendance.”