If voting was an assignment, thousands of Newark ballots would be marked “incomplete” this year.

Fewer than half of the roughly 54,000 Newarkers who headed to the polls for last Tuesday’s midterm elections voted on each of the two education-related questions on their ballots, according to preliminary numbers from the Essex County clerk’s office.

One question asked Newark voters whether they wanted an elected or appointed school board. The other asked voters across New Jersey whether the state should borrow $500 million to pay for school improvements.

A large majority of Newark voters who answered those questions opted for an elected board and to approve the bond measure. But an even larger number of Newarkers who showed up to the polls — some 32,000 voters — left each of the questions blank.

Confusing ballot designs appear to have caused problems in elections in New York and Florida this month. In Newark, some voters said they didn’t understand the ballot questions or know enough to answer them, while others said they overlooked them.

“I didn’t even notice them,” said Ernest Cooper after leaving a Central Ward poll booth on Nov. 6. “A lot of people are going to miss that.”

In Newark, about 38 percent of registered voters turned out for the election, which included congressional and municipal races, or mailed in ballots. That is vastly more than the 5 percent who turned out for April’s school-board election, which was held separately from the mayoral election. But when it came to the public questions on last week’s ballot, only about 16 percent of registered Newark voters participated.

Newarkers were not alone in voting for candidates but skipping the public questions. Statewide, nearly 3 million voters cast ballots in the U.S. senate race — yet only 2.1 million voters weighed in on the education-funding question, according to results compiled by the Associated Press. That means nearly 869,000 voters who participated in the election sat out the referendum.

It’s possible that greater participation could have swung the results of the referendum, which asked New Jersey voters to approve borrowing for vocational programs, school security upgrades, and projects to improve the quality of schools’ drinking water. The measure passed by about 6 percentage points — a difference of just 127,511 votes.

In Newark, it’s unlikely the outcome would have changed even if more voters had completed their ballots. About 75 percent of the roughly 23,000 voters who answered the public questions favored an elected board, while 86 percent approved the bond measure.

Research suggests that voters may suffer from “decision fatigue” as they move down the ballot, making them more likely to reject or skip down-ballot proposals. A recent study of San Diego elections found that voters were more likely to vote down state propositions, or abstain from voting on them, when the questions appeared lower on the ballot, according to The Atlantic.

In Newark, voters at two Central Ward polling places gave different explanations on Tuesday for why they skipped the ballot questions.

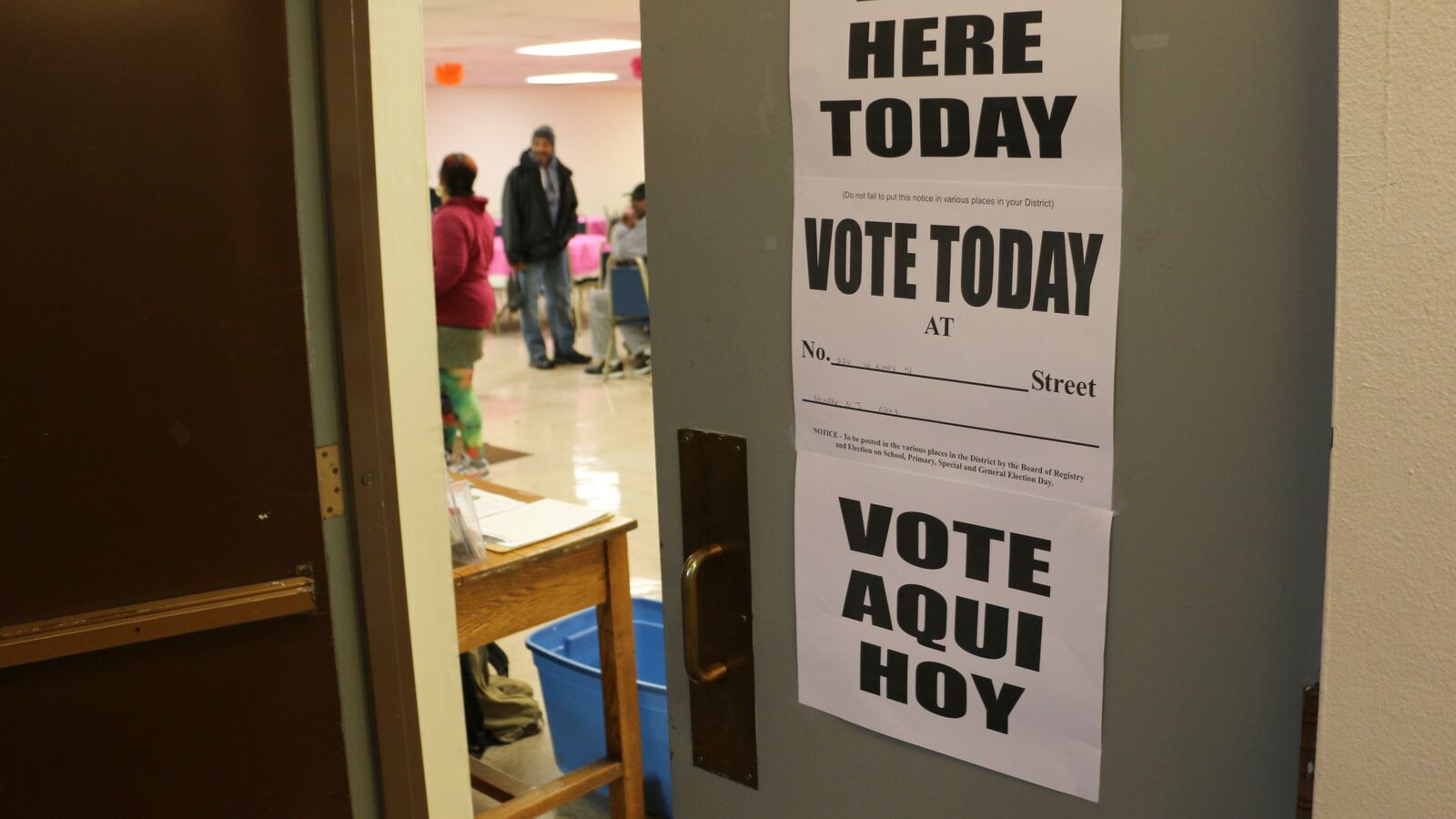

A few, like Cooper, said they had not seen or read the questions, which were written in English and Spanish on the right side of ballot. Others said they felt too ill-informed to weigh in or — as in the case of a charter-school parent — unqualified to vote on the district’s school board.

Debora Walker, a worker at the Abyssinian Baptist Church polling site, said her team was trying to alert voters to the questions. But many voters were unfamiliar with the issues, which officials had done little to educate them about before the election, she said.

“They didn’t advertise it enough, and nobody’s taking the time to read it,” Walker said. “We can just tell them about it — we can’t make them do it.”

In an interview before the election, Mayor Ras Baraka said his administration had hosted a public information session about the school-board question and posted a message he wrote about it on the city’s website. He also said he would ask district leaders to remind voters to answer the questions on election day.

“We’re trying to get the word out,” he told Chalkbeat.

“Will it impact them enough to say, ‘I’m going to go out there and make sure I participate in this’?” he added. “I’m not 100 percent convinced of that.”