The city’s complicated high school application process makes low-income and non-English-speaking students more likely to wind up in low-performing schools, some advocates and researchers say.

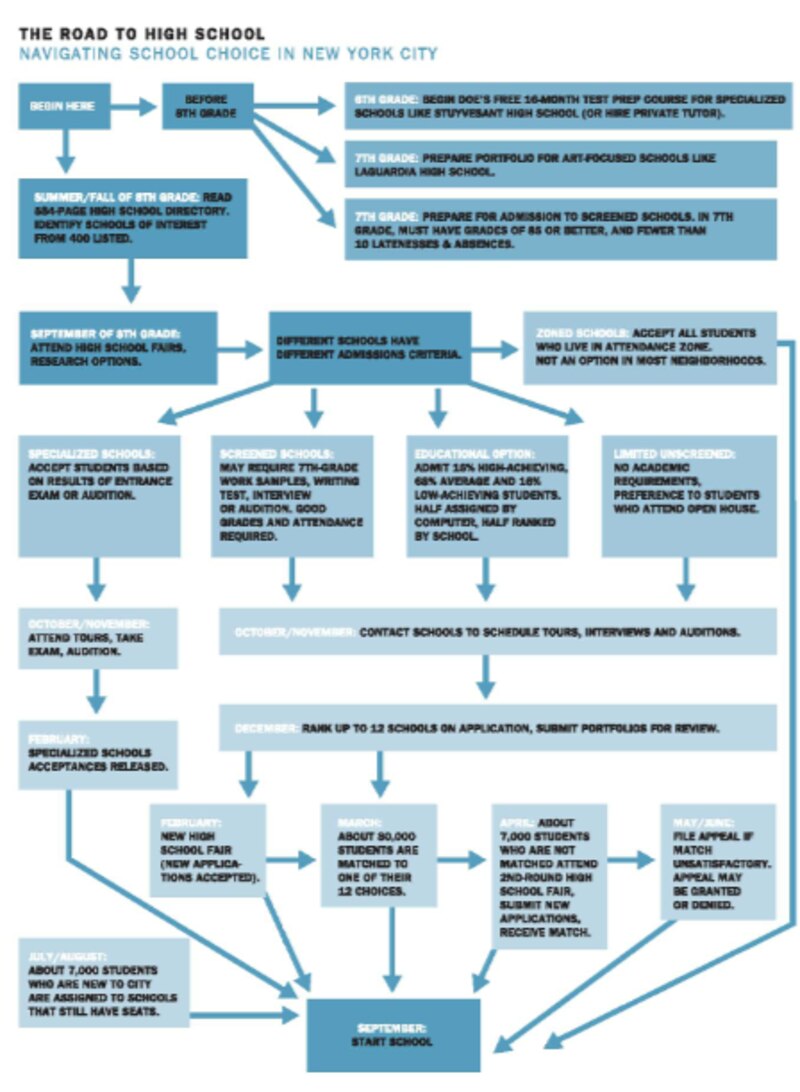

To get into high school, New York City students must navigate a labyrinthine application process that can stump even the savviest parent. The Center for New York City Affairs illustrated the process with a flow chart in its recent report about small schools.

The report found that a disproportionate number of the city’s neediest students continue to wind up in large, lower-performing high schools, even as the number of small schools has increased. Their concentration has in turn caused the large schools to struggle even more, the report concluded.

The city’s primary source of information intended to help families maneuver though the process is its annual directory of all 500-odd high schools. This year’s 640-page directory is being distributed to seventh graders before the end of the week, with one major change: Now, schools’ progress report grades and quality review ratings are included. Before last year, each school’s page included its 4-year graduation rate and its math and English Regents exam passing rates. Last year’s directory included no performance data at all.

The new data is more robust than what the directory included before, according to a department spokesman, Andrew Jacob. That’s because the progress report grades take into account graduation rates and Regents pass rates as well as other performance data, Jacob said. The reports have been criticized for being difficult to understand and not statistically sound, although their critics have said the high school metrics are more reliable.

Flimsy high school information can lead to bad choices, especially for 13-year-olds who are navigating the application process largely on their own, according to panelists speaking last week at discussion about the small schools report.

One problem is that when schools advertise, they don’t always share the complete or most accurate picture, said New York University professor Pedro Noguera.

Another problem, he said, is that middle school guidance counselors often do not have the resources they need to help students make good decisions.

Steven Duch, the principal of Hillcrest High School in Queens, agreed, saying the sheer number of high schools, combined with guidance counselors’ workloads, means the counselors have little more information than students can find in the directory. “They don’t know what the high schools look like,” he said. “They haven’t visited, they dont have information at their fingertips. They probably dont have the data.”

(One place where counselors could find a lot of this information is on Insideschools.org, the Web site that provides school reviews written by trained reporters along with comments from parents, teachers, and students. But Insideschools is set to close up shop next week unless it secures substantial new funding. I used to work at Insideschools.)

High school choice has been a mixed bag for the city’s neediest students, panelists said. “You have to have the resources to access the choice,” said Noguera.

“On the other hand, no choice meant Thomas Jefferson for all of the kids in East New York,” responded Clara Hemphill, the panel’s moderator and the lead author of the report. She was referring to the large high school in Brooklyn that the city closed in 2007 because of its poor performance.