New York City’s heralded $75 million experiment in teacher incentive pay — deemed “transcendent” when it was announced in 2007 — did not increase student achievement at all, a new study by the Harvard economist Roland Fryer concludes.

“If anything,” Fryer writes of schools that participated in the program, “student achievement declined.” Fryer and his team used state math and English test scores as the main indicator of academic achievement.

The program, which was first funded by private foundations and then by taxpayer dollars, also had no impact on teacher behaviors that researchers measured. These included whether teachers stayed at their schools or in the city school district and how teachers described their job satisfaction and school quality in a survey.

The program had only a “negligible” effect on a list of other measures that includes student attendance, behavioral problems, Regents exam scores, and high school graduation rates, the study found.

The experiment targeted 200 high-need schools and 20,000 teachers between the 2007-2008 and 2009-2010 school years. The Bloomberg administration quietly discontinued it last year, turning back on the mayor’s early vow to expand the program quickly.

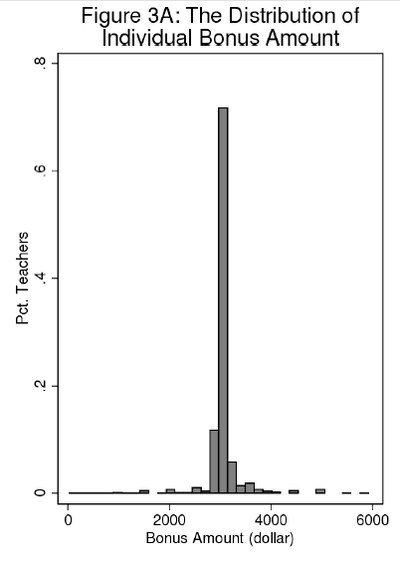

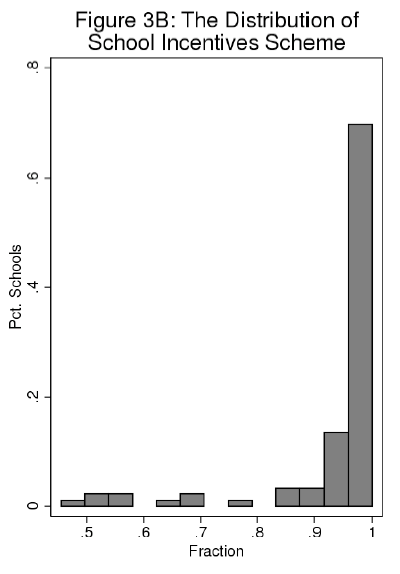

The program handed out bonuses based on the schools’ results on the city’s progress report cards. The report cards grade schools based primarily on how much progress they make in improving students’ state test scores. A so-called “compensation team” at each school decided how to distribute the money — a maximum of $3,000 per teachers union member, if the school completely met its target, and $1,500 per union member if the school improved its report card score by 75%.

The deal was seen as a landmark in 2007 when Mayor Bloomberg announced it with then-United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten by his side. “I am a capitalist, and I am in favor of incentives for individual people,” Bloomberg said then, while Weingarten emphasized that schools could decide to distribute bonuses evenly among educators. She called the program “transcendent.”

In his study, published as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Fryer writes that researchers were surprised to see that schools that won bonuses overwhelmingly decided to distribute the cash fairly evenly among teachers. More than 80 percent of schools that won bonuses gave the same dollar amount to almost all of the eligible educators.

Researchers were also surprised to find that middle school students actually seemed to be worse off. After three years attending schools involved in the project, middle school students’ math and English test scores declined by a statistically significant amount compared to students attending similar schools that were not part of the project.

The study adds to a research literature on teacher incentive pay that is decidedly more lukewarm than much of the popular conversation about teacher pay. Fryer, himself a strong early advocate of experimenting with financial incentives to improve student achievement, calls the literature “ambivalent.” While programs in developing countries such as India and Kenya have had positive effects, few teacher incentive pay efforts in the United States have been deemed effective.

Nevertheless, a person’s position on teacher merit pay has become a litmus test for her reform credentials in many education circles. During his campaign, President Obama used his support for merit pay — traditionally scorned by teachers unions — as evidence that he was willing to challenge traditional Democratic Party thinking. Now, the Obama administration has boosted support for the Teacher Incentive Fund, a program that funds local experiments in incentive pay.

What explains the discrepancy between programs in the U.S. and elsewhere? Fryer rejects several explanations. He argues that the $3,000 bonus (just 4 percent of the average annual teacher salary in the program) was not too small to make a difference, citing examples of effective programs in India and Kenya that gave out bonuses that were an even smaller proportion of teachers’ salaries. He also rejects the possibility that schools’ decisions to use group, rather than individual, incentives was the problem, citing a 2002 study of a program in Israel that used group incentives.

Instead, he says the challenge is that American plans aren’t clear about what teachers can do to receive the reward. In New York City, the bonuses didn’t come simply if students’ test scores rose; the test scores had to rise in comparison to a group of similar schools. So did other measures considered by the city report card, including the surveys that ask students, teachers, and parents for subjective opinions about schools.

Fryer argues that the complexity made it “difficult, if not impossible, for teachers to know how much effort they should exert or how that effort influences student achievement.”