Erica Zigelman has watched from up close as the city’s approach to preparing school leaders has evolved over the past decade.

In 2005, she was in the second graduating class of the NYC Leadership Academy, the fast-track principal training program with a paid yearlong residency, which the Bloomberg administration created to mold a new corps of leaders to carry out its policies.

Today, Zigelman still heads the Washington Heights middle school she founded after her training, even as the city relies less on the academy to train principals like her. But she now mentors aspiring principal-assistant principal pairs and rising teacher-leaders who are in new training programs meant to prepare the next generation of school leaders.

“It’s all about the pipeline,” said Zigelman, who spent two decades in the school system before founding M.S. 322. “You’ve always got to look for your up-and-coming leaders.”

The Leadership Academy was designed to fill gaps left by the city’s longstanding process to become a principal, in which educators work their way up within schools over time. But with about 200 principal slots to fill each year, the city has recognized the need to branch out beyond its boutique principal-training academy.

Fueled by a $12.5 million grant, the city has lately adopted what one recent report called an “all-of-the-above” approach: It has found less costly ways to prepare principals on its own and to seek out potential leaders earlier in their careers, while at the same time working more closely than ever with hand-picked training partners, which are also trying out new strategies.

Meanwhile, Chancellor Carmen Fariña, a former principal, has proclaimed her vision of school leader as master teacher and collaborator-in-chief. But apart from a shift in the principal-eligibility rules, it remains to be seen how her thoughts on the role of school leaders will affect how they are trained.

“I ask myself that question every night,” said Joshua Thompson, the executive director of the New York City and Newark office of New Leaders, one of the city’s training partners. “It’s definitely to-be-determined.”

Former Chancellor Joel Klein launched the Leadership Academy a decade ago to fill a surge of expected school vacancies with principals trained to apply a corporate-minded focus on data and results to school management.

But starting with its first class of 77 graduates in 2004, the academy has never produced enough principals to replace all those who leave the system. And because of the academy’s steep cost — its students pull in administrator salaries while training under mentor principals — the city has paid for fewer and fewer participants, down to just 20 this year.

The city has also driven down costs by creating its own principal training program, which relies on the Leadership Academy for curriculum and recruitment support, but has participants keep their jobs in their own schools rather than apprentice elsewhere. It has also reduced the Leadership Academy’s residency from a full to a half-year.

To draw even more quality principal candidates into the system, the city in recent years has decided to work more closely with outside training groups.

After scrutinizing different programs, city officials chose to partner with three universities and two nonprofits, New Leaders and the Leadership Academy, out of about two dozen such programs that operate in the city. It also encouraged the Relay Graduate School of Education, a new institute with strong ties to the charter-school sector that had previously only trained teachers, to pilot a program for aspiring principals.

The city has helped the programs recruit promising principal candidates, pay for some of their costs and for some students’ tuition, tailor their courses to the city’s needs, and find placements for their graduates. It has pushed them to tie their admissions criteria, curriculums, and assessments to the city’s Quality Review rubric, which is used to rate schools and principals.

Kenneth Grover of Bank Street College said the city’s outreach has spurred the school to share training ideas with the other partner institutions, Fordham University and Teachers College. And it has given the school a clearer sense of the city’s expectations for principals.

“We have a greater understanding of what’s being done and why,” said Grover, chair of the school’s educational leadership department, “which has given us more time to integrate it into our program.”

Much of the department’s work with the partners is funded by a multi-year grant it was awarded in 2011 by the Wallace Foundation, a New York-based philanthropy that helped fund the launch of the Leadership Academy.

The grant stipulates that a significant number of graduates from the city’s revamped training programs or its partners’ must be heading schools by January 2015. Those programs currently have 229 participants, according to the city.

The principals will be evaluated using the city’s new online database, which can match administrators with school data, such as teacher-retention rates, attendance, and student test scores, according to Jody Spiro of the Wallace Foundation.

Soon, the foundation will ask the city to focus its improvement efforts on the principal-training groups it did not choose as partners, according to Spiro, Wallace’s director of education leadership.

“The objective is to raise the quality of all the preparation programs,” she said.

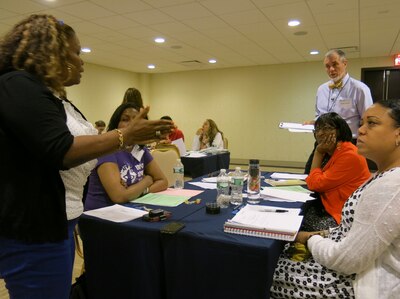

The city and its partners have also started over the past few years to seek out exceptional educators before they are ready to run their own schools. The education department, New Leaders, and the Leadership Academy now offer programs that let teachers, instructional coaches, and assistant principals sharpen their leadership skills without committing to become principals.

The moves are partly an effort to catch potential leaders who might not have considered running a school. But they are also an acknowledgement that the Leadership Academy and other fast-track trainings, which initially let some teachers leap from the classroom into the principal position without experience managing adults, left some unprepared for the job.

“At the beginning, there was a trend of, ‘Look, the system is broken and we just want to get new people in there,’” said Verta Maloney, New Leaders’ managing director of programs. “That really doesn’t work.”

Fariña responded to concerns about unprepared principals during her first month on the job, when she said that aspiring school leaders now need seven years of in-school experience instead of three. The policy change drew gasps and then cheers at the principals meeting where she announced it.

In fact, department officials had already checked and found that only a handful of aspiring principals would not meet the new requirements. At New Leaders, for instance, the average would-be principal today has worked in schools for about eight years, Maloney said. And at the Leadership Academy, only one person in last year’s 22-person cohort would have fallen short of the seven-year requirement, according to its director.

More significant may be Fariña’s call for principals to spark cooperation among educators, which has inspired a new school-partnering program and provisions in the new teachers contract that require joint teacher-administrator committees. Irma Zardoya, CEO of the Leadership Academy, said she had “talked a lot” with Fariña about the need for principals to “create shared decision-making in their schools.”

Jody Spiro of the Wallace Foundation said Fariña’s emphasis on collaboration is backed by research, with the most successful schools having high levels of “collective leadership.” The challenge is training future principals to foster those conditions, she added.

“What’s critical is that these themes of Carmen’s get translated into the preparation programs,” she said.