Stories of low-performing students being encouraged to leave charter schools have long fueled criticism of the city’s charter-school sector. But a new analysis of enrollment data shows that low-performing students are just as likely to leave district schools as they are charter schools.

According to the new research, when it comes to a student’s likelihood of leaving a school, “The combination of being low-performing and charter is not different from being low-performing and public,” said Marcus Winters, the researcher who conducted the analysis.

The report was published by the conservative Manhattan Institute, which hosted a discussion of the findings on Thursday that became a feisty referendum on charter school enrollment policy, just as state lawmakers consider increasing the number of charter schools statewide.

“If we’re going to have a conversation about whether or not we should expand the charter school sector in New York City, those conversations need to be grounded in the real data and not just anecdotes,” Winters said.

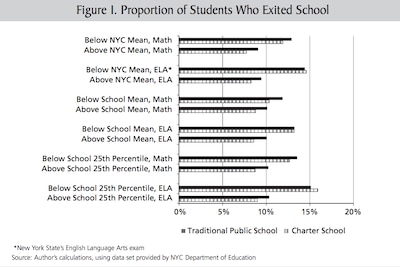

Winters used Department of Education data from all district and charter schools from the 2006-7 school year to the 2011-12 year. The analysis looks at students in fourth, sixth, seventh, and eighth grades — excluding the fifth-to-sixth grade transition, in which most city students switch schools — and analyzed what happened to three kinds of “low-performing” students using state test scores: students who scored lower than citywide averages, those who scored lower than most students at their schools, and those in the bottom 25th percentile at their schools.

Attrition of low-performing students looks similar at district and charter schools, he found. (Winters didn’t focus on which schools had the highest or lowest attrition rates, but attrition rates ranged from 5 percent to more than 20 percent at 13 schools whose charters were up for renewal earlier this year.)

But while many district schools have to fill the open seats left when students leave, charter schools do not — something the report doesn’t acknowledge.

Many schools fill vacant seats, known as “backfilling,” for financial reasons or as part of a mission to serve as many high-needs students as possible. But not doing so, other operators say, enables schools to support their remaining students without the disruption of bringing in new students. It also means that schools with those policies would likely see average test scores increase over time, Winters acknowledged.

The debate took a combative turn at the Manhattan Institute panel, driven primarily by founder and former CEO of Democracy Prep Public Schools Seth Andrew.

“Are charter schools doing all they can to serve the neediest students? Resounding no,” said Andrew, who has recently been focused on encouraging other charter school networks to replace students who leave.

Andrew left Democracy Prep in 2012 to work as an advisor at the U.S. Department of Education. Once an outspoken critic of the teachers union, Andrew has waded back into the city’s education debates as a gadfly within the charter school sector as the founder of the parent group Democracy Builders.

During the panel, Andrew confronted other panelists, accused philanthropists in the audience of “subsidizing the kids who leave” with their private donations, and criticized the media for fixating on test scores as a sole measure of school quality without additional information about who is enrolled at the school.

The time to start “backfilling” students is now, he told the audience.

“Find a way to do it and find a way to do it today, because this train is coming and you want to get on board,” said Andrew, who said he plans to release a report next week with more details about the issue.

The panel also included New York City Charter School Center CEO James Merriman and Public Prep charter school network CEO Ian Rowe.

As lawmakers in Albany continue to debate whether the state’s charter-school cap should be raised, the panel reflected the tension within the city’s charter school sector between those seeking to keep the focus on its triumphs and those like Andrew, who say highlighting its shortcomings is healthier in the long term.

“As we move from laboratories of innovation to at least partial replacement or alternative to the district at scale, I think the answer at least politically and, for me, morally, certainly is yes we need to do more, have to do more and can do more,” Merriman said.

During a question-and-answer portion of the event, Derrell Bradford, a board member of Success Academy and CEO of New York CAN, an advocacy organization, said he “violently disagreed” with Andrew’s focus.

“I don’t think you can have that discussion without also having a discussion about scarcity in district schools,” Bradford said afterwards. “I just think this really needs to be about more good schools, no matter where they are, not just about whether or not we should be squeezing more needy kids into charter schools that already exist.”