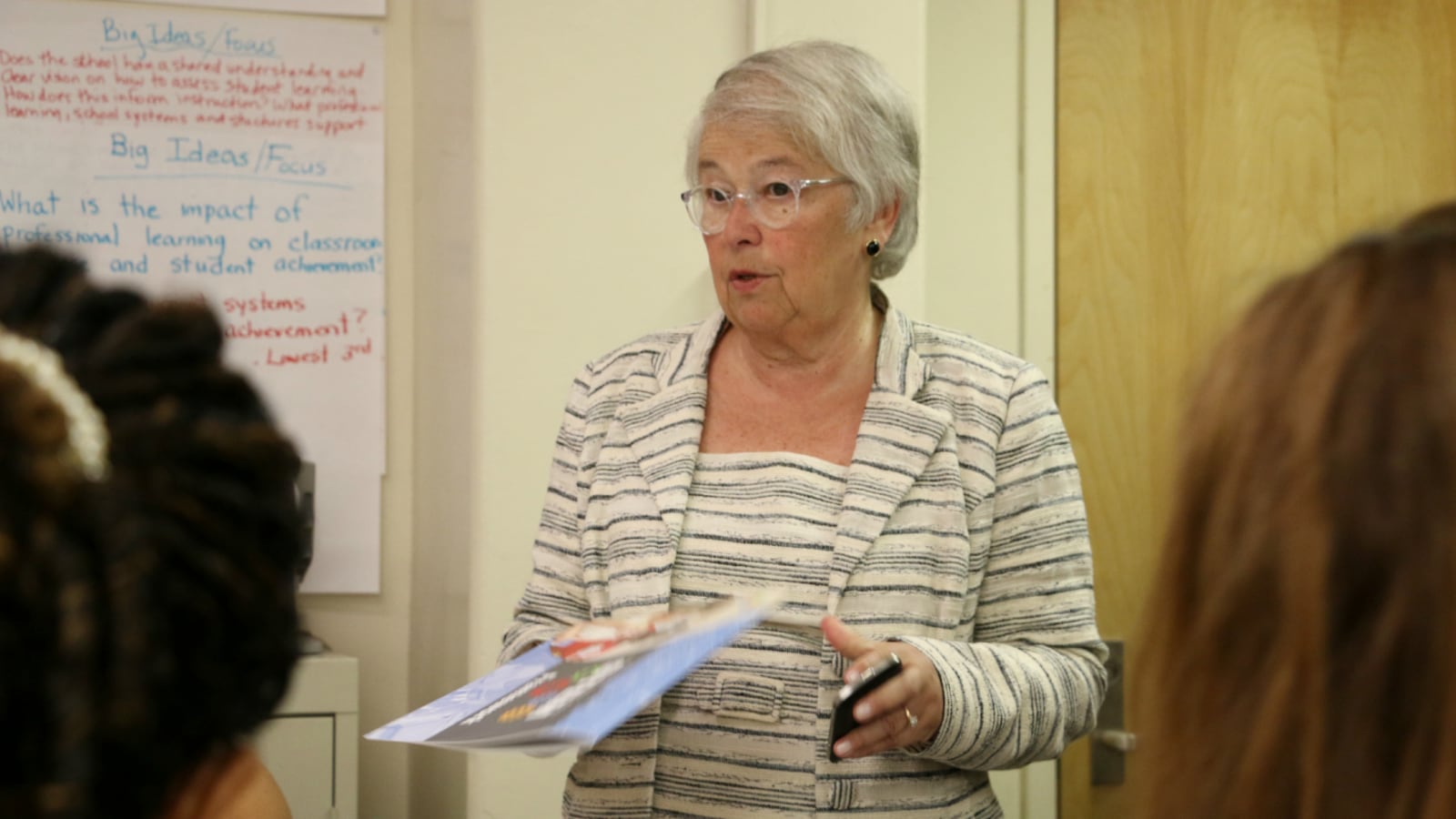

A year and a half ago, when schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña addressed concerns that Manhattan’s District 1 was becoming increasingly segregated, her advice was simple. Individual schools, she said, needed to focus on doing a better job of selling themselves to attract more diverse student bodies.

But at an almost identical town hall meeting Tuesday evening, an auditorium of parents heard a different message. Fariña called school diversity “one of my top three priorities,” and said that she is open to broader ideas to boost diversity as long as they bubbled up from communities themselves.

“We’re looking for many ideas,” she said. “We’re hoping for at least 10 different ways of doing this that make sense … I want to see diversity in schools organically. I don’t want to see mandates.”

Fariña was not asked to address the specifics of any proposals at the town hall meeting. But her comments — in line with recent statements that she wants local leaders, not the education department, to take the lead on diversity — were a welcome change to Community Education Council 1 President Arnette Scott.

Fariña’s sentiment “represented a shift,” said Scott, who has been rallying support around an effort to make changes to the district’s choice-based school enrollment policy. “It represented a little more room to try to implement a district-wide change.”

Unlike many of the city’s other local school districts, the current enrollment system in District 1 lets parent preferences, not specific addresses, dictate where their children are enrolled in elementary school.

And though it’s unclear what role the choice-based policy has played in each school’s demographic makeup, the pattern in District 1 is clear. A report found that as recently as 2000, just a single District 1 school had a racial makeup significantly different than the district at large. By 2011, 20 schools showed substantial signs of racial segregation.

There’s some debate over whether the district’s unique enrollment policy caused the clustering of white and minority students, especially given a 2007 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that limited the use of race as a factor in enrollment decisions. But some district officials nonetheless hope that a “controlled choice” policy will help ease the disparity.

Changes to the enrollment plan, according to Scott, could take into account factors such as whether a child receives free or reduced price lunch, lives in temporary housing, or is an English language learner – all to help guarantee that these “at-risk” students are distributed more equitably across the district’s schools.

The district has not created a formal proposal yet, though Scott said that half of the schools in District 1 had signed onto a resolution in support of the philosophy of controlled choice. Details about how the plan would actually work would be ironed out through a community process, she said.

(Two of the district’s schools are already involved in a pilot program to set aside 45 percent of their seats to low-income students, though Scott said that will only make “a very small dent.”)

For her part, Fariña did not comment on controlled-choice policies. She did, however, hint that there are ways around legal strictures that prevent schools from directly considering race, including by more evenly distributing students who receive free or reduced-price lunch.

And while some parents at the meeting said they didn’t know much about controlled choice, others thought it couldn’t hurt to try.

“I’m all for it,” said Joe Kaufman, a parent of a first grader at the East Village Community School, a school that has a larger share of white students than the district. “Growing up in a multiracial city, it makes sense to have a school with the same population.”