For years, Peter Cipparone and Kim Van Duzer taught math next door to each other at P.S. 29 in Brooklyn. And while they each puzzled over how to convey the power of fractions to fourth graders, they almost never compared notes.

So, about two years ago, they did something obvious yet surprisingly uncommon: They observed each other’s classes and had conversations about what they saw.

“We learned a lot from watching each other teach,” Cipparone said. “That seems like a very simple practice, but it’s amazing how rare that is.”

The pair found their conversations so useful that they helped start NYC Math Lab, a program designed to give more teachers a chance to watch each other teach elementary math, and improve their instruction by discussing what they saw.

The idea behind the math lab is to break down some of the barriers that can get in the way of that kind of teacher training: Coordinating schedules, finding a group of students who are available to be observed over several days, and perhaps most importantly, overcoming the tradition of classrooms being closed to outsiders.

“At first we were really nervous – teaching is so private,” recalls Van Duzer of her first experiences teaching for an audience of peers.

Based on a successful first run last summer, the program is gearing up for its second year and is accepting applications for 25 teachers to participate this July. But its founders hope to expand the number of teachers who participate in the future – by moving to a larger space or running new labs – to encourage more teacher training that includes live observation and analysis.

“Sometimes I go to [professional development] sessions where there are no kids and I go back to my classroom and it doesn’t go so well,” Van Duzer said. At the math lab, she notes, “If it doesn’t work, we’re going to tinker with it.”

The lab isn’t just about helping teachers, though – its founders are trying to excite students who may have been told they’re not good at math. All of the students who participate in the math lab do so as part of an existing summer program offered by the Hudson Guild, a community based organization that serves low-income families.

“In society, there [have] been fairly clear messages about who can and can’t do math,” Cipparone said. “And this breaks down that stereotype effect.”

Cipparone, Van Duzer, and Kate Abell, a veteran New York City teacher who helps coordinate teacher training throughout the city, founded the program in part to promote a less traditional way of teaching math. Instead of thinking about math as a series of procedures that have to be memorized and applied, they construct lessons that require students to understand and debate fundamental concepts and speak up when they don’t get it.

In one typical lesson, for instance, students are given a series of differently sized wooden rods and asked to assemble them on a number line. Then, they’re tasked with having a conversation about which rods represent what fraction of the line and must defend their answers.

“Math teaching can be very oriented around, ‘Did you get it right? And if not, then you don’t get it,’” Van Duzer said. “We tell them, ‘In this community, it has to make sense to you.’”

The lab follows the same structure each day. Teachers spend the morning going over a lesson plan, working through the problems they’ll be asking students tackle. Next, the lab’s three founders rotate teaching that day’s two hour teaching block while the other 25 teachers sit around the perimeter and watch students work through the lesson.

The full group of teachers spend the afternoon reviewing each student’s work, analyzing the lesson, and making suggestions to improve the next day’s teaching. Finally, they talk about how students’ ideas about math develop in relation to Common Core standards.

Later in the week, the teacher observers can work one-on-one with students to focus on each student’s thinking, something that is often difficult in the context of a typical class period.

The idea of public teaching as a way of improving instruction was directly inspired by the Elementary Mathematics Lab at the University of Michigan, which helped pioneer the model over a decade ago (and where Cipparone is currently working on a doctorate).

[Chalkbeat CEO Elizabeth Green has written extensively about the history of teacher training, including Michigan’s math lab. You can find a Q&A with her here.]

But according to Nicole Garcia, who directs the university’s math lab, the New York lab is the first known offshoot of their model.

“I think it’s amazing to see somebody take up this work and try to bring it to their own context,” Garcia said. “It is a little bit surprising that there aren’t more efforts to do this kind of work.”

Figuring out whether the New York math lab is actually having an effect on the way its participants teach is a challenging question, its founders note, and one they’re trying to address. For the first time this year, they received a $6,000 grant to track participating teachers before and after the lab to see how their instruction changes.

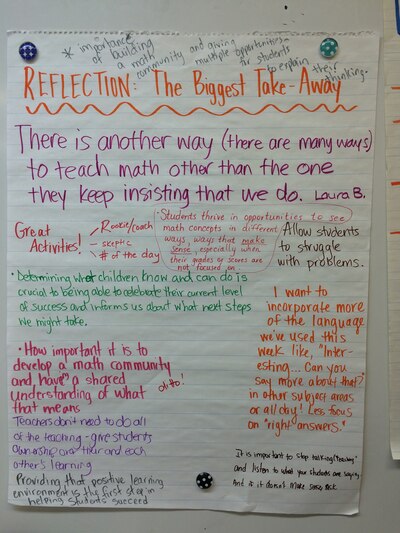

Still, they acknowledge that the math lab isn’t about disseminating one correct teaching method that everyone is supposed to adopt – it’s about having conversations that can make teachers more thoughtful educators.

“We are not saying this is model teaching,” Cipparone said. “We’re saying this is teaching for all of us to study.”