Schools will no longer be allowed to suspend students in kindergarten through second grade, one of a series of new safety policies announced Thursday that includes creating a process for removing metal detectors from some school buildings.

The decision to end suspensions for some of the city’s youngest students comes after a city task force issued its second and final report that spells out a series of recommendations aimed at making the school system’s disciplinary practices more fair.

This past school year, 801 suspensions were issued for students in kindergarten through second grade, down from 1,454 the previous year, an education department official said. The new policy will replace those suspensions with “age-appropriate discipline techniques” according to a press release.

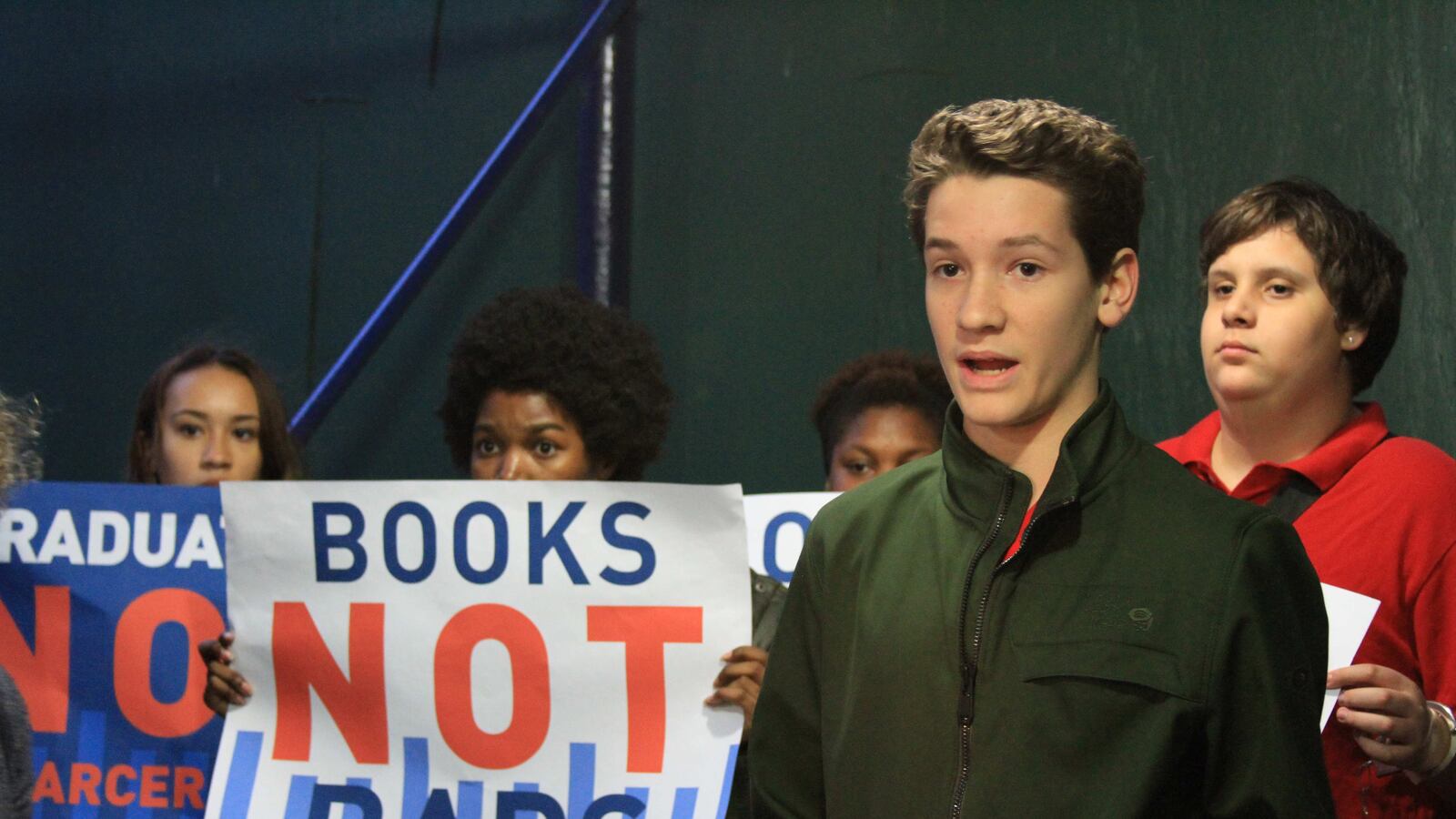

Advocates largely praised the new suspension policy, though some thought it didn’t go far enough. “It’s progress – it’s a step in the right direction,” said Kesi Foster, a coordinator at the Urban Youth Collaborative, and a member of the city’s task force. “Transformative change would expand that same understanding and compassion” to high school students, he added, and eliminate suspensions for older students as well.

The new suspension policy drew criticism from United Federation of Teachers President Michael Mulgrew, who wrote a letter to schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña blasting the decision. “The new plan claims that the DOE will provide schools with additional resources to address the challenges created by banning suspensions,” he wrote. “We are skeptical these new supports will materialize.”

Moving schools away from punitive discipline toward more restorative practices has been a hallmark of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s school reform strategy, but has met mixed reviews. The recommendations issued Thursday come from a city task force, which includes top officials. It was created to move the city away from practices that lead to students getting tangled in the criminal justice system, and which disproportionately affect black and Hispanic students, as well as those with disabilities.

The city also promised to implement a new procedure for removing metal detectors from school buildings, or only use them “part-time,” taking into account factors such as school size and weapon-related student activity near the building, an education department official said. Eighty-eight of the city’s 1,300 school buildings use metal detectors, according to the city, but according to a WNYC analysis, nearly half of all black high school students pass through metal detectors, compared with just 14 percent of their white peers.

“It’s very vague exactly what they’ve been doing or will do,” said Johanna Miller, advocacy director at the New York Civil Liberties Union, and member of the city task force, in reference to the metal detector policy. “We think they’re positive developments, but will be monitoring implementation.”

The city used the report to tout reductions in suspensions and crimes committed within schools — which have been the subject of a wider public relations battle with charter school supporters.

The NYPD also issued new statistics that include data on how often students have been handcuffed, and the number of arrests made by officers on school grounds.

According to a preliminary analysis of the data by the NYCLU, there were 1,555 student arrests last school year, and 436 student arrests this year from January through March.

Of the 436 arrests in the first quarter of 2016, just nine — or 2 percent — were white. And while 70 percent of the city’s students are black or Hispanic, that group represented 92 percent of arrests, according to a Chalkbeat analysis.

“Similar to street policing, racial disparities in school-based arrests are severe,” according to an NYCLU press release.

While the NYPD data show crime in the city’s schools is down roughly 50 percent since 2004, according the NYCLU, the new statistics also reveal almost 673 uses of restraints during the first quarter of 2016. Eighty-three of those incidents involved students who were emotionally disturbed.

Black and Hispanic students were also more likely to be restrained. Of the 673 restraints, 627 — or 93 percent — were used on black or Hispanic students. Two percent involved white students, Chalkbeat found.

In an interview, an NYPD official acknowledged the disproportionate effect policing has on black and Hispanic students, but said the department is open to discussions on how to eliminate it.

In its announcement, the city also promised to allocate $47 million annually “to support school climate initiatives and mental health services,” including adding mental health supports in 50 additional schools over the next three years.

“Today’s reforms ensure that school environments are safe and structured,” de Blasio said in a statement. “In partnership with the NYPD, my administration will continue to monitor school safety data to ensure enduring reductions in disciplinary disparities while improving school safety citywide.”

Annie Ma contributed data analysis