A Brooklyn city councilman who is becoming a leading voice against segregation wants every middle school in his local school district to reserve some spots for poor students.

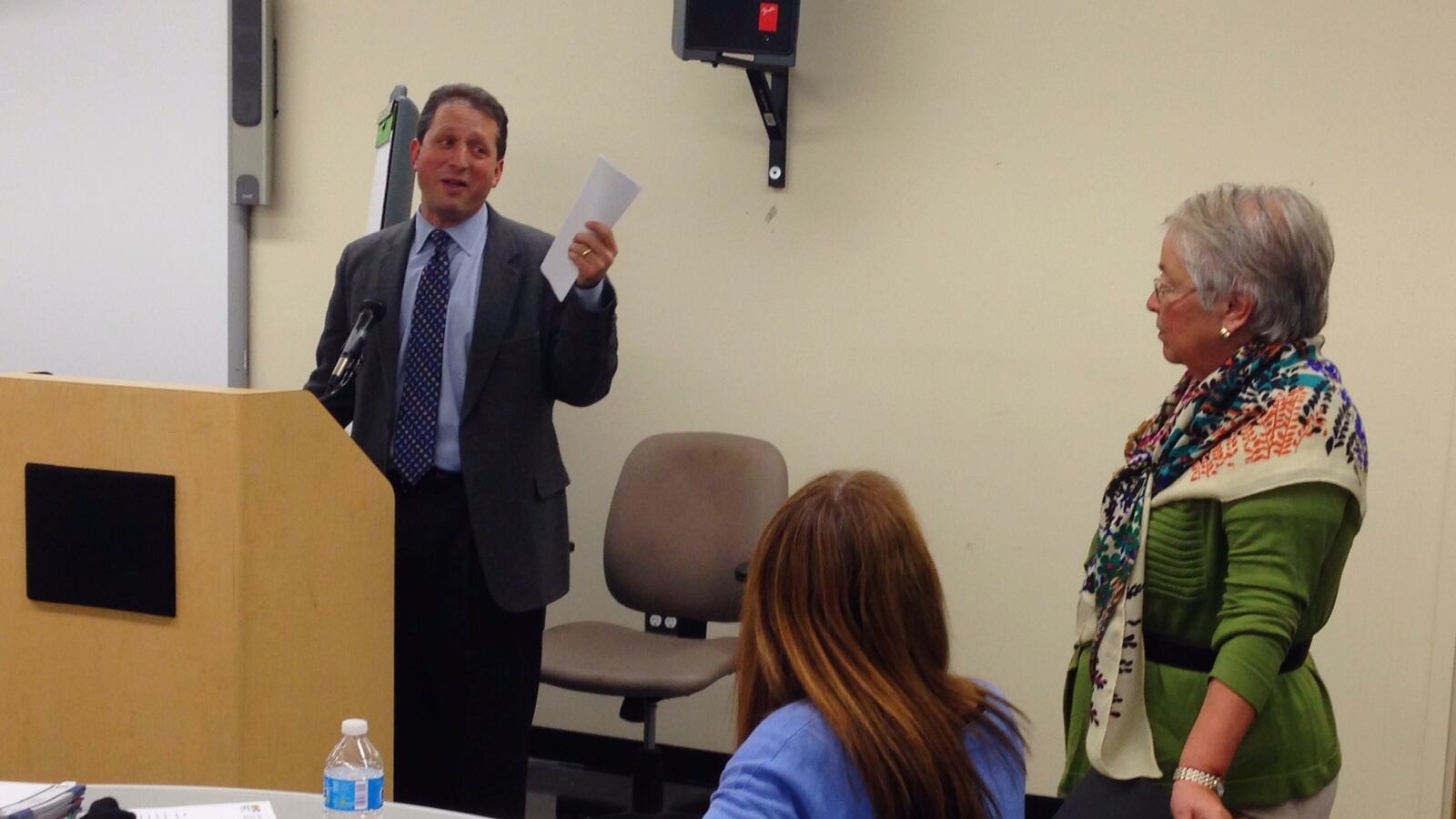

Under Councilman Brad Lander’s proposal, each middle school in District 15 would set aside a percentage of seats for students from low-income families — just like schools in the city’s new Diversity in Admissions initiative, which allows schools to change their enrollment policies to boost student diversity.

But parent leaders say more comprehensive reform is needed to take advantage of the district’s unusual potential for diversity. According to Lander’s own simulation, the proposal might increase the number of poor students at only three schools in the district, which is heavily stratified by race, class and academic achievement.

“It’s not going to achieve something like full integration in which every school would have demographics that would match the demographics of the district. What it is, in my opinion, is a meaningful step forward,” Lander said.

Lander called his proposal an “idea” rather than a concrete plan — and only one step towards broader changes.

It’s unclear how a district-wide set-aside would be implemented. So far, the Diversity in Admissions program has required individual schools to opt-in. The District 15 Community Education Council is expected to further debate the proposal at its next meeting.

In District 15, 16 percent of students are Asian, 15 percent are black, 38 percent are Hispanic and 28 percent are white. But 81 percent of white students are concentrated in just three of the district’s most selective schools, according to an analysis by parents.

And while 66 percent of students are poor enough to qualify for free or reduced price lunch, they are not distributed evenly throughout the district. Some schools serve virtually only poor students, while others have as little as a quarter of students from low-income families.

A group called Parents for Middle School Equity argues that the district’s admissions policy ultimately must change to make a real difference.

School segregation is often blamed on housing patterns and attendance boundaries. But District 15 has a “choice” policy for its middle schools, and each school sets its own admissions criteria. Reyhan Mehran, a member of the parent group, said the system favors plugged-in parents with the time and resources to navigate an opaque and complicated process.

“It ultimately sorts the kids in this district into two groups of schools: one that educates the majority of our higher-needs kids, and those schools happen to educate most of the Latino kids,” she said. “And another group of schools that educates most of our lower-needs kids. And those schools happen to educate most of the white kids in our district.”

Lander has said he also supports “broader reform” when it comes to the admissions process. Parents for Middle School Equity has not advocated for any particular solution, only saying that community input is needed to pinpoint the problems and come up with potential fixes.

Superintendent Anita Skop said the district has already taken steps to make the application process more fair, like making sure selective schools conduct outreach in both well-heeled and working-class communities. She has also started a diversity committee to start talking about district-wide issues.

Before making wide-scale changes, Skop said she wants to make sure she hears from a broad range of parents.

“I do not have the right to speak for people whose skin I don’t live in, whose shoes I don’t wear,” she said.