When the head of New York City schools suggested that English Language Learners fail to graduate, in part, because they lack formal schooling and are “coming from the mountains,” advocates from a group that serves Haitian immigrants said she undoubtedly missed the point.

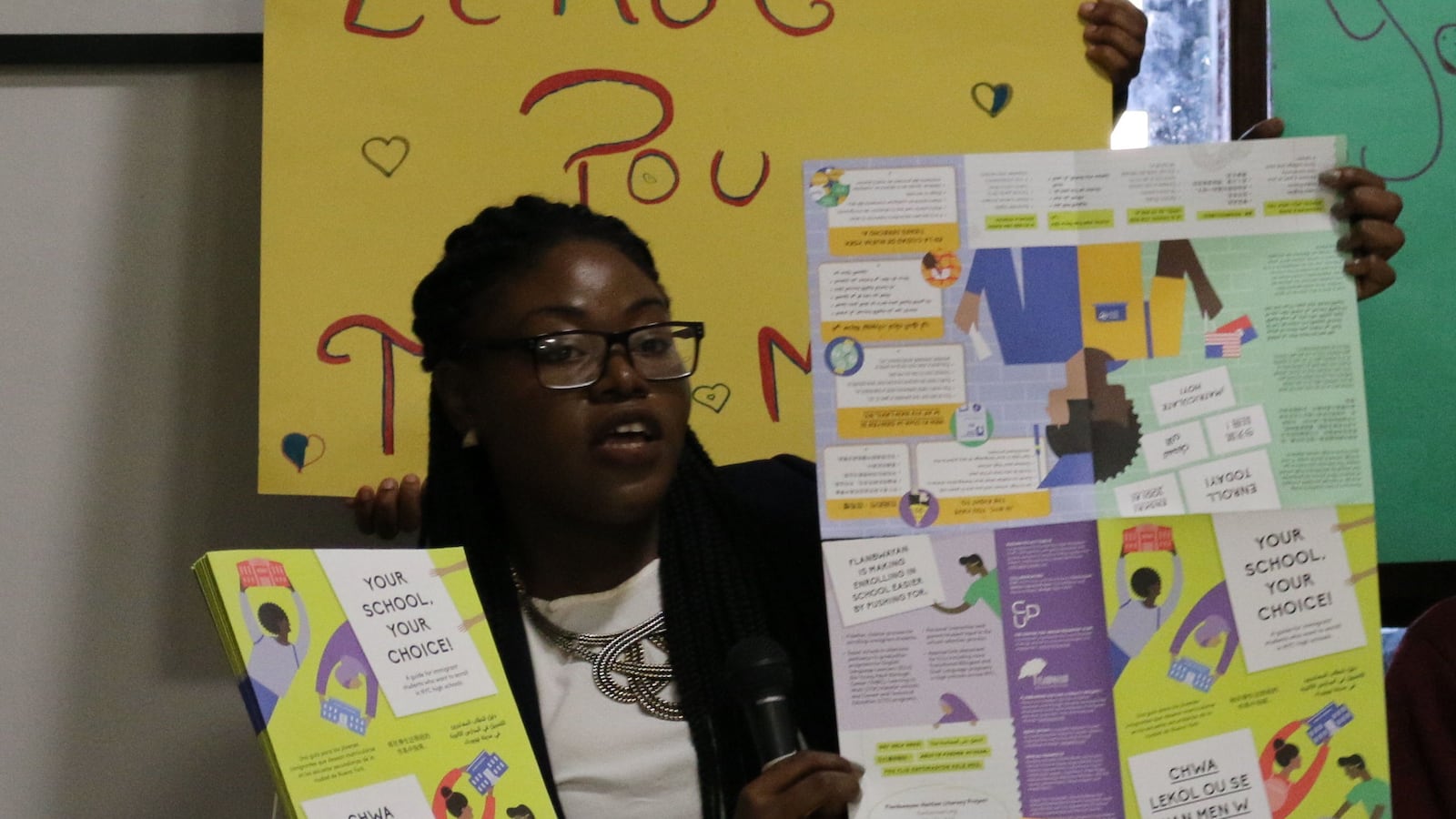

“We are insulted by her statement,” said Nancie Adolphe, a case manager at Flanbwayan, a group that helps young Haitian immigrants, during a Thursday press conference. “As a community of immigrants, of English learners, we care about what happens to each student, no matter where they come from.”

The city pointed out that combining current and former English Language Learner graduation rates, 57 more students graduated this year. Fariña also said that while she is working to help more English learners graduate, it is harder for students to earn a diploma if they start off years behind.

Members of Flanbwayan have a different explanation for the city’s 27 percent June graduation rate for English learners, a 9.6 percentage point decrease over the previous year. In their view, many ELL students face a huge disadvantage because of how the city’s high school admissions process treats newly arrived immigrants.

New York City’s admissions process, which allows students to apply to any high school throughout the city, is notoriously difficult even for students born and raised in New York. But for newly arrived immigrants, the process is even worse, said Darnell Benoit, director of Flanbwayan.

Students have years to wade through a thick directory of more than 400 high schools, tour the ones they like and apply for competitive programs. For new immigrants, that process is often replaced by a quick trip to an enrollment center. Many times the only seats left are at low-performing schools, and students often find they don’t have access to the language help they need, Benoit said.

“They don’t have a lot of time to fight for their lives,” said Alectus Nadjely, a Haitian immigrant who arrived in the United States when she was twelve and is now a senior in high school, about the process.

A student’s high school placement is directly connected to whether or not they will graduate on time, advocates said. When newly arrived immigrants enter the country, they have to move quickly to pass the state’s required exit exams in time for graduation — and they need all the support they can get, advocates said. Twenty-seven percent of English learners in New York City drop out before graduating, according to state data.

“If a student is not set up in the right placement from the start, the likelihood of being able to stay engaged, be on track for graduation and not drop out, all of that will be impacted,” said Abja Midha, a project director at Advocates for Children. “We really think the high school enrollment piece is a really critical point.”

Education department officials pointed out that the graduation rate for former English learners went up by more than five percentage points this year. They also noted that enrollment information is available in Haitian Creole and that they have increased translation and interpretation services.

“We’ll continue our work to ensure that all our students receive a high-quality education,” said education department spokesman Will Mantell, “and have the support they need to be successful in the classroom and beyond.”

This story has been updated to include additional information.