Before 2015, principals only had to seek approval from the city for the most serious suspensions. But starting in April of that year, the city added an oversight mechanism: Requiring principals to get permission from the education department before suspending students in grades K-3, or a student in any grade for insubordination.

Some school leaders and union officials complained, saying the policy makes it harder to maintain order.

But how often does the city overrule a principal’s judgment?

In all, the education department rejected about 22 percent of suspension requests under those categories during the 2015-16 school year, the first full year under the new code. Officials rejected 453 of the 2,008 requests to suspend students for insubordination, or 23 percent. And they rejected about 20 percent of the 1,039 attempts to suspend students in grades K-3, or 31 percent if you include the more serious suspensions that already required approval.

“It is promising to see that there are rejections and that suspensions are not rubber-stamped by the Department of Education,” said Dawn Yuster, the school justice project director at Advocates for Children. “They’re using this as a way of showing schools they’re serious about the policy changes.”

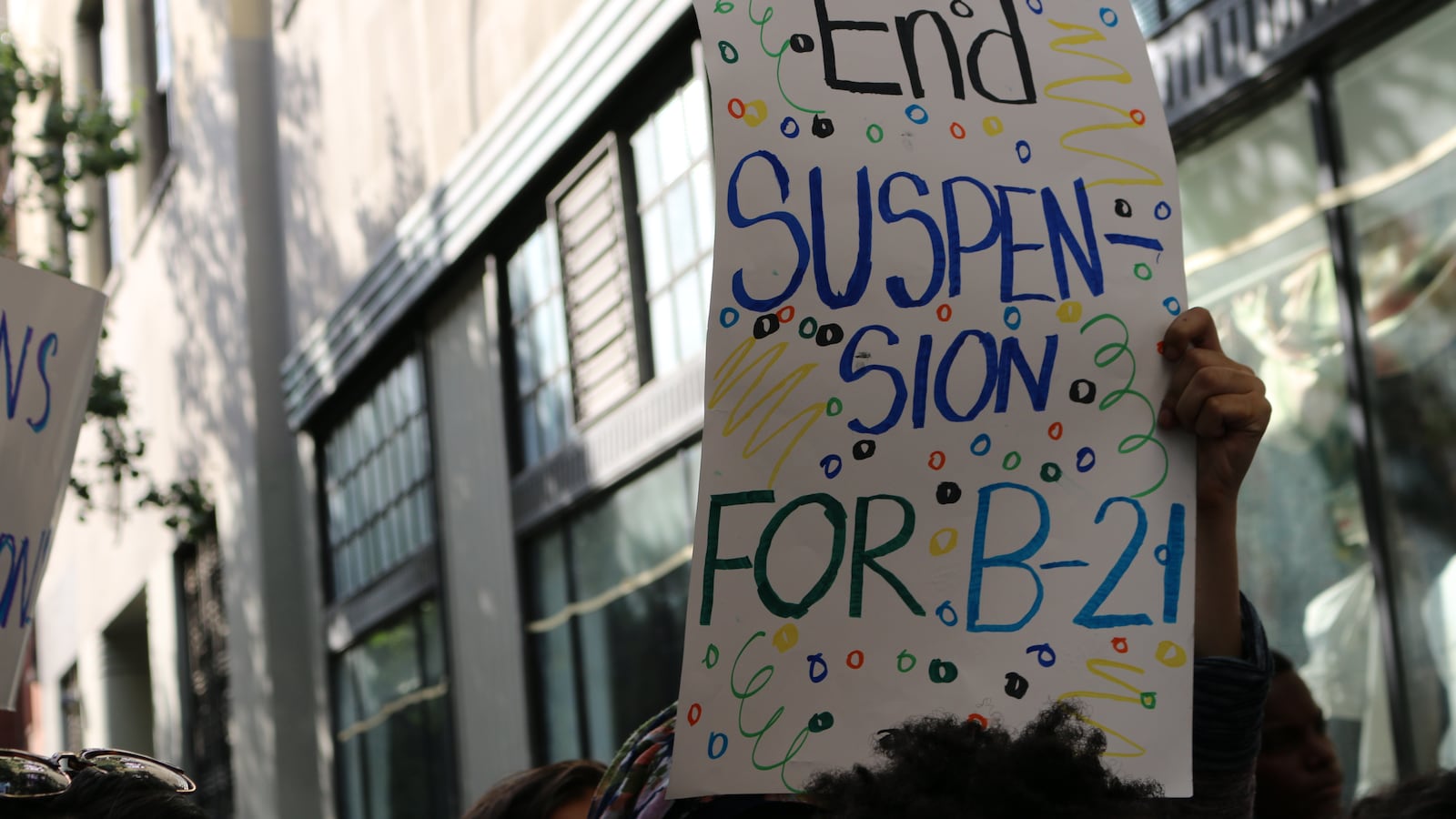

The requirement that principals earn approval for certain suspensions came as part of a series of edits to the discipline code — championed by Mayor Bill de Blasio — designed to discourage their use and move schools toward less punitive approaches.

The number of total rejections (659) is tiny compared to the total number of principal suspensions issued last year (27,122). (Principals have long been required to clear more serious superintendent suspensions with the department; last year, schools issued 10,525 of them and were rejected 2,171 times.)

Still, in concert with the city’s shift away from suspensions more generally, the decision to require an extra layer of approval in certain cases may be having an effect. Overall, suspensions have fallen by roughly 30 percent under de Blasio’s watch, continuing a downward trend that began under his predecessor.

“There’s kind of an unwritten rule where schools know these suspensions aren’t going to be approved, so schools don’t put a whole lot of them through,” said Damon McCord, co-principal at the Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School in Queens.

Officials have taken particular aim at suspensions for insubordination, one of the offenses that now requires approval. Advocates charge that its inclusion in the discipline code contributes to the disproportionate removal of students of color and those with disabilities from their classrooms — and its use has plummeted 75 percent over the past two school years. The city has also pledged to virtually eliminate suspensions for the city’s youngest students (that policy is expected to take effect later this month).

But the dramatic drop in suspensions has earned mixed reviews from some educators who say there has been a parallel dip in discipline. Ernest Logan, head of the city’s principals union, argues school leaders should be trusted with suspension decisions, as long as they’re following the discipline code.

“When the chancellor selects a principal, then you should give that principal the authority to run their schools,” Logan said in response to the rejection numbers. “Why do you have a principal there if you don’t accept their judgment?”

Lois Herrera, CEO of the education department’s Office of Safety and Youth Development, which oversees the suspension approval process, said the extra layer of oversight ensures students are only suspended if they are actually interfering with their peers’ educations. “We saw it as an opportunity to add that extra quality control and make sure if we had to suspend, it was appropriately used.”

Suspensions are more likely to approved if the misbehavior constitutes a pattern, interferes with instruction, or other alternatives have been exhausted, Herrera said, noting that forthcoming updates to the discipline code will “strengthen” the requirement that schools try other options first.

“If we say no [to a principal], it doesn’t mean we’re turning a blind eye to misbehavior,” Herrera said, because her office often helps schools find alternative approaches. Asked if principals could simply suspend students for similar infractions that don’t require approval, she said she there was no evidence of that in the data.

McCord, the Queens principal, said the education department rejected his attempt to suspend a student who repeatedly tried to skip afternoon classes. “We probably didn’t do a good enough job articulating the prior interventions we’d already done,” he said.

Still, he supports the city’s review policy.

“We just found other ways to address [misbehavior],” he noted. “If you’re working that hard to suspend a kid, you probably need to rethink your approach.”