Before the Achievement School District, before Tennessee allowed charter schools, before Memphis became “Teacher Town,” there were the Catholic Diocese of Memphis’ Jubilee Schools.

The network of schools launched in 1999 with a mission to educate poor students in Memphis, regardless of their religion. The mission made the Jubilee Schools different from Catholic school networks in other cities, which had been closing schools at unprecedented rates. It also placed the schools at the forefront of a movement toward school choice in Memphis that was on the verge of accelerating.

“Jubilee Schools were a really significant first wave of reform in the education setting in Memphis,” said David Hill, director of academic operations for the Catholic Diocese of Memphis.

Now, the schools are among the leading advocates for a new controversial form of school choice in Tennessee: vouchers, which would let low-income families zoned to low-performing schools use public funds to pay for private schools. Lawmakers have left voucher legislation on the table in each of the last two years, but sources including lobbyists, researchers at Vanderbilt University, and a Democratic opponent of the program, say vouchers are likely to get the okay next year.

Although its impossible to be sure of what next year’s legislation would look like, the introduction of vouchers could dramatically change the Jubilee Schools’ financial picture. And it would further complicate the web of school options that parents in Memphis already have. Right now parents that would be offered vouchers can already send their students to schools run by the Achievement School District (many of which are charter schools), charter schools outside of the ASD, or the Shelby County Schools.

Jubilee Schools could stand to gain more than $2 million from vouchers if they managed to fill all their classroom space, meaning that Shelby County Schools and the Achievement School District would receive less. If vouchers become a Memphis reality, other players in school choice will have to react.

“We’d have to step up our game and make sure we have schools where parents want to send their kids,” Chris Barbic, the head of the statewide Achievement School District, said of the post-voucher educational landscape.

The voucher debate in Tennessee

The bill that made it through the State Senate this year would have made vouchers available only to students zoned to the bottom 5 percent of schools in Tennessee. Almost all of those students live in Memphis, although that might change when the state releases a new list of priority schools later this month. The vouchers would either have covered tuition at a private school or let families apply the amount that the state and district together spend per student toward the tuition. And the number of vouchers covered would have grown from 5,000 in the program’s first year to 20,000 two years later.

Until now, opposition from two groups have stopped similar bills that have cropped up the in Tennessee Senate since 2011.

On one side, there are those who say the voucher legislation is not expansive enough, and should include a greater breadth of Tennessee children. In 2013, Sen. Brian Kelsey, a Republican from Germantown, was at the forefront of a push for an expansive voucher program that would impact students across the state, not just in the bottom 5 percent of schools. This year, he supported the legislation limited to low-income families. Gov. Bill Haslam has insisted he will only sign voucher legislation targeted at low-income students.

The other group argues that voucher bills would deplete the budgets of already cash-strapped schools. Democratic representatives and the Tennessee Education Association, the state’s largest teachers union, have been among the most vocal proponents of that argument.

“When we talk about Tennessee now being behind Mississippi in funding per child, it just seems silly to talk about vouchers,” said Alexei Smirnov, the managing editor of TEA’s magazine.

Barbara Cooper, a Democrat representative from Memphis, echoed concerns about the allocation of school funding at a recent community meeting in Frayser. Families living in Frayser, a neighborhood already dominated by the Achievement School District, would qualify for vouchers under last year’s proposed legislation.

“I think we need to be careful about that,” Cooper said. “ It’s helping [schools] that are rich already.”

Around the country, uncertain results

Thirteen states and the District of Columbia already offer voucher programs. Some of those states only offer vouchers to students who receive special education, but seven extend vouchers to students attending academically-struggling schools and from low-income families. Indiana’s legislation allows even families making up to $62,000 year to use vouchers.

Researchers haven’t reached consensus on the impact of vouchers. In the 2012-2013 school year, students in voucher programs in Milwaukee and Cleveland performed worse on average than their peers in public schools on statewide assessments, and in Louisiana, seven private schools had such low test scores they were prohibited from further accepting vouchers. Other studies have found that voucher programs have improved public schools and increased the likelihood of high school graduation.

Sometimes, more choices does not equal good choices. In Milwaukee, home of the oldest voucher program in the United States, a crop of financially mismanaged and low-achieving private schools popped up after legislation was passed in 1992.

Tennessee’s proposed legislation troubleshoots such pop-up schools by requiring that schools be fully accredited by the state department of education or an agency approved by the department of education at least two years before they can accept voucher payments. The accreditation process takes at least two years, said Claire Smrekar, a researcher at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College of Education.

Most students who use vouchers in states with programs that extend beyond special education go to previously-established religious schools. In Indiana and Washington, D.C., more than half of these schools are Catholic, although in North Carolina, the most popular school with parents using vouchers is Islamic.

What vouchers could do in Memphis

While Memphis’ Jubilee Schools has spots for 500 students, it’s not clear how many poor students would take advantage of those seats. It is clear they could never educate all of the city’s poor students. Many other independent schools are not interested in accepting vouchers. This spring, researchers from Vanderbilt University did a study of private schools in the Memphis area. After interviews with more than 50 heads of schools, they found most of the private schools either could not or did not want to accept vouchers.

That might encourage legislators redrafting the bill for the next session to ease up requirements for private schools accepting vouchers, said Smrekar, who led the study. Or, of the 20,000 students who would eventually get vouchers, many — maybe even the vast majority — might not find a private school that would accept them.

The reasons private schools might not accept vouchers range from financial to ideological. Private schools could not charge more than the voucher amount, just a fraction of what some schools charge. Annual tuition for students in grades 9-12 at Lausanne Collegiate School, for example, is $20, 610.

Additionally, many schools are neither set up nor feel a calling to take students who might have fallen several grade levels behind and get them up to speed, Smrekar said. And many more don’t want the government regulation that would come with government funding.

But since the Jubilee Schools already accept Title 1 funding from the federal government, and offer free and reduced lunch, they’re used to government oversight, administrators say. Students also already take nationally-normed standardized tests twice a year, another stipulation in last year’s proposed voucher bill.

“They’re ready,” said Carra Powell, a lobbyist for Tennessee Federation for Children, and parent of two in Jubilee Schools and one recent graduate. “As soon as the voucher bill is passed, we’re rolling them in.”

But it’s not clear how great the demand for vouchers in Memphis is. Although choice has expanded significantly in Shelby County in the past decade, with 41 charter schools in operation, few, if any of those charter schools have waiting lists, and many parents still opt to go to their neighborhood school. And a new study by the Center on Reinventing Public Education shows that school choice doesn’t necessarily equate to increased access to better schools because of barriers like transportation and parents lacking or misunderstanding information schools provide.

Inside Jubilee

Administrators and teachers at Jubilee Schools think they have a lot to offer families currently in public schools.

Catholicism is a central part of the education offered at the Jubilee Schools, and the diocese prides itself on offering a faith-based education, said David Hill, the academic director for the dioceses and a former charter school principal. A crucifix hangs in every classroom, and students attend mass weekly.

Of the more than 1,000 students who attend Jubilee Schools, most practice a religion other than Catholicism. Most of the teachers aren’t Catholic either, nor is Hill. The diocese’s goal is for students –92 percent of whom are black or Hispanic, with virtually all of them receiving need-based scholarships–have been in Jubilee Schools since at least third grade to average in the top third on a nationally normed standardized test, the Iowa Assessments, by the sixth grade. More than three-quarters of Jubilee students met or exceeded their expected achievement growth on the Iowa Assessment in English and math, as determined by the Riverside Publishing Company’s Estimated Growth Report for the Iowa Assessment Core Composite during the 2012-13 school year, Hill said.

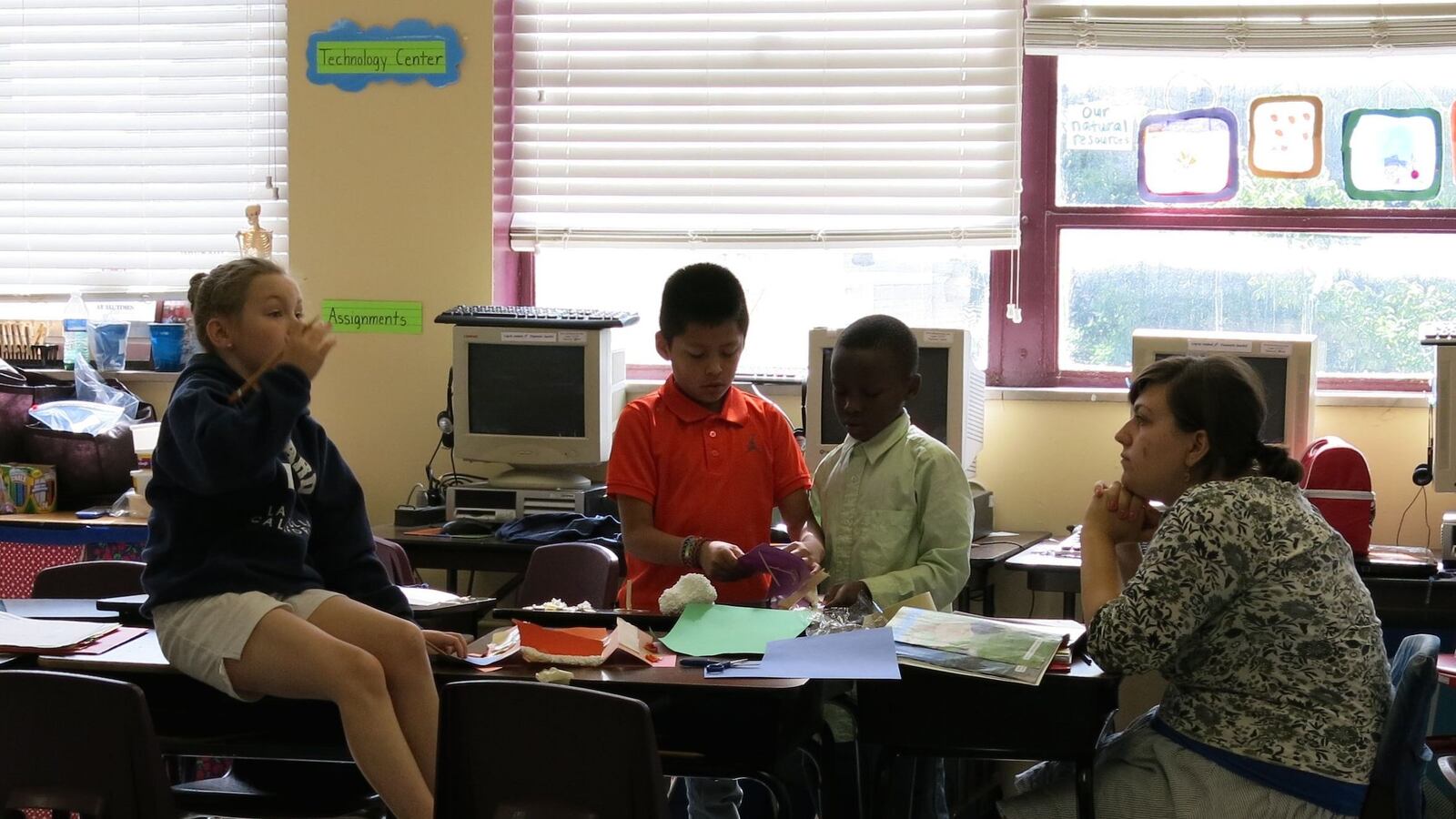

The schools collaborate with the University of Memphis to make sure that growth can happen. This summer, after noting a problem endemic to all schools, students losing knowledge during the summer months, the schools and the University of Memphis decided to hold a summer reading program at De La Salle Elementary School in Midtown. Each day, about sixty third-and-fourth graders from eight of the Jubilee Schools come to De La Salle for breakfast, lunch, and reading activities. Teachers include some from Jubilee Schools, some from other schools in the diocese, and University of Memphis doctoral students. The students are broken into groups of around eight students, depending on their reading level.

On a recent Monday, the program went to Booksellers, a bookstore in East Memphis. Some of the students had never bought a book before, said program coordinator Erika Hansen. By that Wednesday, the students were reading about Ancient Egypt and making jewelry Ancient Egyptians might have worn. (“We’re rich Egyptians,” a third grader explained.)

“It’s really about instilling a love of learning,” Hansen said.

Carra Powell says she’s experienced the schools’ ability to bring kids to grade level firsthand. Before her divorce, her children had gone to a private Montessori School in Mississippi, but as a single mother, she couldn’t afford to keep them there. Her oldest daughter seemed to do fine in the public schools. But her son, who started at the local elementary school in kindergarten, still couldn’t read by the second grade. Powell is quick to say that she does not want to bash the public schools. But, she said, they weren’t working for her son, and she didn’t know what to do.

Some of her friends were Catholic, and recommended she look into Jubilee Schools. Powell went to visit St. John, a Jubilee School in Orange Mound. She said she walked in and talked to the principal, and started to cry. To Powell, now a lobbyist for the Tennessee Federation for Children working on voucher legislation, the Jubilee Schools seemed a godsend.

She said the school was able to get Nicholas up to grade level by working with him on reading in a small group four times a week. He also participated in a book group with the principal after school. In a single school year, his reading test scores improved by 60 percent.

And the small size of the school allowed teachers to provide her daughter, who was above grade level in math and reading, with an individualized curriculum. Her daughter recently graduated from St. John, and is attending St. Agnes, another Catholic school, on a merit scholarship. Powell’s son, an eighth grader, is never without a book. “He reads himself to sleep,” she said.

Powell said that her work as a lobbyist is infused by her children’s experiences. “I want other people to be able to access these schools,” she said.