In a city where arguments over charter school growth are volleyed back and forth like a tennis ball in a Grand Slam tournament, tennis champion Andre Agassi is bringing his star power to the debate — and hopes to turn a profit in the process.

Agassi and his business investment partner Bobby Turner on Tuesday celebrated the opening of Rocketship United Academy, the second Nashville school opened by California-based charter network Rocketship Education. Like with Rocketship’s first Nashville school, which opened last fall, this $7 million-plus, 37,000-square-foot building was developed through a fund created by Agassi and Turner.

Nationally, affordable facilities are considered one of the greatest challenges to charter expansion because charter operators often must raise their own money for school buildings. The issue has fueled scraps both in Memphis and Nashville, where school board members and district officials complain about the cost of charters to traditional public schools, even without providing facilities or funding for facilities. Charter advocates counter that charter schools are public schools too — authorized by local districts and sometimes the state — and should be provided with buildings and facilities like any other public school.

The Turner-Agassi Charter School Facilities Fund, a for-profit business, provides the capital to purchase property for charter schools, constructs or retrofits the building, and then rents to a charter operator until the operator can own it.

Agassi says investing in high-quality, learning-friendly elementary schools is the first step in lifting student achievement nationwide. Turner says the goal is to generate a profit for investors while serving a higher public purpose. Investors will get an 8 to 10 percent market rate return from the rental and sale of campuses — and they don’t see anything wrong with that.

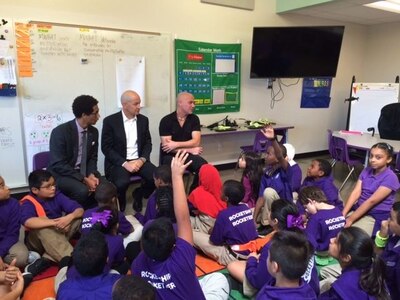

“We didn’t give away money to build this building,” Turner told fourth-graders during a tour of Nashville’s newest Rocketship school. “We call that philanthropy. When we give money away, oftentimes organizations aren’t held accountable.”

The fourth-graders, dressed in their purple Rocketship uniforms, nodded politely before asking which man in front of them — Agassi or Turner — is the famous tennis player.

Agassi, who retired from tennis in 2006 after being a dominant force in the sport for more than a decade, first teamed with Turner in 2011 to create a fund that has helped develop 50 charter schools serving 22,800 students.

Turner said he decided to focus on hedge funds rather than philanthropy after years of giving away his money to build almost 40 schools in Los Angeles. Philanthropy, he said, wasn’t able to create change quickly enough, with three times as many kids on school waitlists as there were seats.

“If we’re going to rely on philanthropy, we’ll never get to address this huge daunting challenge,” he said. “There is nothing wrong with making money while making significant and scalable change.”

Rocketship Education has worked with the Agassi-Turner venture on its two Tennessee schools and one in Wisconsin. A nonprofit charter organization, Rocketship also operates 10 schools in California and plans to expand soon to Washington, D.C. The network is known for its technology-heavy curriculum in serving low-income students.

Jessica Johnson, director of the Charter School Facilities Initiative, said private-public relationships that partner with a commercial real estate developer, solicit private dollars, or use a hedge fund like Agassi’s are becoming more common in the charter world in states and districts that don’t automatically match charters with buildings.

“Because charter schools don’t have access to those same resources, they’re forced to go on the open market,” said Johnson, who is also director of policy and legal initiatives at the Colorado League of Charter Schools.

She added that charters should do their homework before entering into such agreements. “You’re using public dollars, so it’s important to do due diligence in ensuring you’re doing what’s best for your students and communities,” Johnson said.

Rocketship United Academy serves 375 students in kindergarten through fourth grade in a former Nashville office building that has been retrofitted to serve as a center for learning. The 2.3-acre campus originally was developed by a local tractor supply business and now includes a gymnasium, learning lab and 19 classrooms.

Rocketship Tennessee director Shaka Mitchell said the operator having its own building made more sense than leasing a building, as many Nashville charters do.

“We can do things in this space that we’d never be able to find in a leased space,” he said — for instance, cutting skylights into the ceiling and rewiring the building for an instructional model that relies heavily on computers. Rocketship spends between 12 to 16 percent of its annual budget for Tennessee on facilities, which is less than Tennessee charter schools’ average of 20 percent, according to the Tennessee Charter School Center.

Mitchell said if critics have a problem that a profit is being made on Rocketship’s customized space, they should instead start a conversation about using public funding for charter facilities. “But right now, that doesn’t even seem to be on the table,” he said.

Turner said he’s interested in building more Rocketship schools in Nashville, but is frustrated by the local school board’s hesitancy to approve a third Rocketship school. The State Board of Education will announce later this month whether it will overturn the local board’s decision and allow Rocketship to expand in the city next year.

Agassi leaves most of the talk about market-rate returns to Turner. When asked by a fourth-grader how they “got money,” Turner told them to find something they love to do. His famous partner agreed.

“You can be wealthy and unhappy,” Agassi said.