Raleigh Egypt Middle School principal Ronnie Mackin looks ahead in a conference room wallpapered with printouts of every metric used by the state and local district to measure student success: test scores, attendance numbers, statistics about fights and suspensions.

The numbers are foreboding: Mackin’s efforts in two years have produced some gains, but not enough to keep his job as principal of this 500-student school in north Memphis. The state is taking over in July.

But Mackin says he won’t let the impending changes distract him, not in these delicate next six months filled with questions and uncertainty. “I have to stay focused. I have a school year to finish,” he says.

Supporting him through the transition are the principals at two neighboring schools on their three-school campus.

Raleigh Egypt Middle School is unique because it shares a compound with Egypt Elementary, from which it receives its students, and Raleigh Egypt High School, where it sends its students. The geographic closeness has helped the schools forge a symbiotic relationship unlike any other feeder system in Shelby County Schools.

Come this summer, however, that dynamic will change. Scholar Academies, a state-approved nonprofit charter network based in Philadelphia, will take control of the Memphis middle school, seeking to vault it from the bottom 5 percent of Tennessee schools to the top 25 percent within five years.

Yet the state’s involvement is an unwelcome intrusion for many residents and leaders in this close-knit school community, where unprecedented collaboration by the three principals has helped chart nascent, but fragile progress.

Mackin has known Raleigh Egypt High principal Bo Griffin and Egypt Elementary principal Dionna Pruitt for more than a decade, having worked together as teachers and coaches in Millington and Kingsbury before becoming leaders together here. They talk and text on cell phones daily, chat in each other’s school driveways and hash out strategies together to reduce the impact of gangs on their campus and cut down on truancy and delinquency.

As disenchantment in Memphis swells over the state’s Achievement School District initiative to reform chronically low-performing schools, the takeover of Raleigh Egypt Middle might serve as the ultimate test of the ASD’s mettle.

School board member Stephanie Love, who represents this North Memphis district, is worried that the state’s intervention into a key piece of the feeder could jeopardize the success of the whole.

“These principals, they know the neighborhood, they genuinely love those children,” Love said. “And they love each other. It’s like a family.”

Some improvement wasn’t enough

With barely 22 percent of sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders proficient in math and 15 percent proficient in reading, the middle school was due for a dramatic change, say supporters of the state’s school reform and intervention efforts.

“For whatever reason, different efforts there failed to gain traction, so something new was necessary,” said Mendell Grinter, state director of the Tennessee Black Alliance for Educational Options. “I believe Scholar Academies is fully committed to reaching out to the community … and really involving them in the process.”

In recent months, Memphis Lift, a parent advocacy group in the Frayser and Raleigh area of Memphis, has connected with more than 14,000 parents through phone calls, neighborhood canvassing and community meetings. Lift operational manager Johnnie Hatten says the feedback is that parents are “in support of change and they feel that the status quo is not acceptable.” Hatten said some parents complain about a persistent “lack of professionalism with teachers and the administration.”

“A parent of Raleigh Egypt Middle School (said) she had no idea that her child’s school was in the bottom 5 percent of performance until The Memphis Lift canvassed her house,” Hatten wrote in an email. “All in all, the general response Memphis Lift has gotten … is that (parents) are not afraid of change and are excited about the opportunity for their child’s school to do better.”

Love has a different perspective. Less than 10 years ago, she said, the middle and high school campuses resembled scenes from “Lean on Me,” a 1989 movie that dramatized a gang-infested New Jersey school on the brink of state takeover. “It was a place that, if a student was there to just learn, you would feel scared for that student — scared that they would get lost,” she said.

The power of relationships

The three current principals took their posts at the schools within months of each other in 2013 and 2014, ushering in a series of changes.

The middle school has cut suspensions by nearly 40 percent. Parents and teachers credit Mackin for dramatically changing the school’s culture by curbing fighting and gang activity, shooing malingers off school property, and strictly enforcing uniforms to remove hidden displays of gang signs. They say he has made the school a safe place to learn, even improving math performance along the way.

Mackin credits teamwork with his two counterparts on the three-school campus for helping him change his school’s environment.

On a typical school day, he exchanges multiple texts and phone calls with Griffin and Pruitt. Together, they work on strategies for coaching more effective teachers and reaching families with chronically truant children. They share ideas about how to counter the district’s abysmal rate of literacy. And recently, when Pruitt was out sick, Griffin and his 6-foot-3 frame patrolled her elementary school’s halls.

They’ve also counseled and supported each other in trying to turn the trajectory on student test scores. When it seemed that state intervention was all but certain at the high school last year, Griffin believes it was the relationship he’d built with his neighbor principals, along with the academic improvements he put into place, that enabled the school to escape state intervention.

“We really have each other’s back,” Griffin said. “We have the same kids and families going through our schools.”

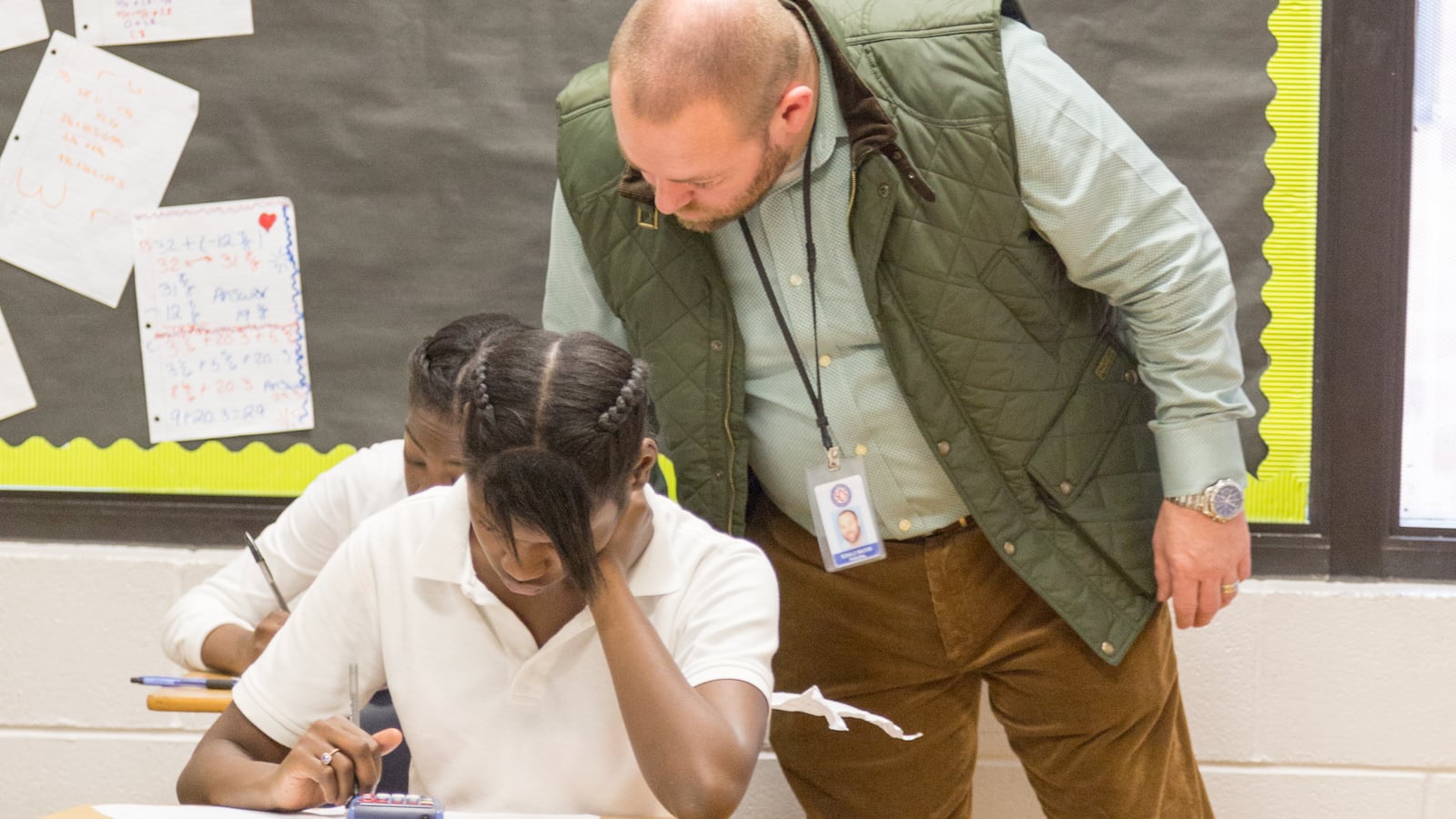

Rarely in his office, Mackin cuts a wrestler’s figure. Stocky and muscular, he is often seen patrolling the hallways and school campus. He makes himself easily available to parents and community members, even printing his personal cell phone number on his business card.

Last year, Mackin focused on improving math performance. He provided teachers with intensive coaching and training and lengthened classes from 55 to 90 minutes. The changes proved hopeful: Students registered 8 percentage-point gains in math. Still, barely a fifth of them can perform math on grade level.

“We’ve really worked hard to build relationships here,” Mackin said. “We are seeing some really good things in just the two years I’ve been here. If I could’ve had just two more years, this school would be totally different.”

Incoming leadership with Scholar Academies are convinced the charter network can take school improvements to the next level. Jerry Sanders, who will take the baton from Mackin, expects to partner with the principals at the other two schools on the campus “for the sake of the kids that we serve academically and socially, not to mention the impact that a strong pipeline of schools will have on the community we serve,” he said in an email.

Sanders said his 13 years of experience in education make him uniquely qualified for the task ahead. He began in 2001 as a substitute teacher at Hanley Elementary and eventually became a special education teacher working with struggling readers at Airways Middle School. Along the way, he earned his master’s degree in teaching from Christian Brothers University. He is also familiar with North Memphis, having spent the last three years as an instructional leader at the KIPP Memphis Collegiate High School.

Rebuilding trust

Sanders can expect naysayers as Scholar Academies takes control of Raleigh Egypt Middle under the umbrella of the Achievement School District. The ASD’s school improvement efforts have come under intense fire in recent months in Memphis, where the state already has control of 27 low-performing schools and will add four more this summer, including Raleigh Egypt Middle.

Last month, some parents rallied against the ASD’s new school takeover process, calling it “biased” and charging that its new community engagement process was a “scam” that didn’t involve parents and neighborhoods in a meaningful way. Just last Monday, the county’s legislative delegation, more accustomed to fielding questions about government funding, was peppered instead with questions about the ASD’s effectiveness.

The ASD’s reputation took a major hit in December when a Vanderbilt University study concluded that ASD schools’ test scores have not risen as much as those of schools in Shelby County’s own school improvement initiative, the Innovation Zone. The study prompted the Shelby County school board to call for a moratorium on ASD expansion in Memphis until it shows “consistent progress in improving student academic achievement.”

The report’s findings, released only days before the ASD announced it would take over more schools in 2016, made news of Raleigh Egypt Middle’s impending charter conversion all the harder to swallow for Shelby County district leaders, educators and other stakeholders.

“This takeover proved to me beyond a shadow of a doubt that this is not about helping children succeed,” said Love, who has been encouraged by improvements happening under the current administration.

"Community engagement is our priority right now."

Jerry Sanders, incoming principal

Incoming principal Sanders is acutely aware of the simmering tension. Though he wants to continue the synergy thriving among the three Raleigh Egypt principals, he says he can’t focus on that yet. Instead he’ll use the coming months to canvass the surrounding neighborhoods and set up meetings with parents and community leaders to learn the pressing needs and expectations for the school’s turnaround.

“Community engagement is our priority right now,” said Sanders, who does not yet have a working relationship with the school’s outgoing leadership.

“Look, I would love to call them up and say, ‘Hey, have you had lunch because I would love to have lunch with you.’ But … that’s not how this works, with all the emotion involved,” he said. “I’m going to have to follow whatever rules of engagement are set out in these situations. That’s just the way it is.”