If the third time’s the charm for efforts to close George Washington Carver High School, it won’t be because the community gave up on the long-struggling school.

Local leaders have sprung to defend the school each time the district has proposed closing it, most recently in a surprise recommendation last month.

“You would think the third time, people think, ‘They’re going to do it anyway,’ so people would not show up to rallies,” said Ralph White, a Carver graduate who is also the pastor of neighboring Bloomfield Baptist Church. “But just the opposite happened. We’ve had better response this time.”

The outcry — and a community proposal to improve Carver — prompted the school board to reconsider the closure last week even as it moved ahead with shutting down other schools last month. Now, the community waits to learn this week whether Shelby County will try to move forward with closing the 198-student school this year, which the cash-strapped district says would save nearly $1 million a year.

Whatever happens, one thing is clear: Carver is one of the only low-performing schools in Shelby County that hasn’t been overhauled or closed in recent years — and uncertainty over its future has surely contributed to its decline.

White’s accounting of Carver’s closure attempts starts in the 1990s. But the contemporary era of school closures in Memphis began in 2012, when the state first named 69 low-scoring “priority schools” in the city that had to either improve or shut down. Almost all of those schools have since been taken over by the state-run Achievement School District; added to Shelby County’s Innovation Zone and given additional resources; or closed. Carver is one of just a few schools on the list not to change at all.

That’s not to say that the district hasn’t considered deploying those strategies at Carver, or that they haven’t affected the school.

Carver first faced closure in 2012, when the Shelby County and Memphis City school districts merged and considered closing schools with low enrollment as a way to use their pooled resources more effectively. Students testified in public hearings against the proposal, and ultimately the new board decided to close only a few schools that year. Carver wasn’t among them.

The following year, the school got what initially seemed to be a boost: The school board voted to fold Riverview Middle School into Carver, which would boost its enrollment and bring new resources. But the board reversed the decision when it realized that closing Riverview could mean giving up federal funds that were being used to improve it as part of the district’s iZone.

At the same time, the Achievement School District was considering adding Carver to its portfolio. A local advisory council set up to help the state-run district match schools to charter operators chose Green Dot Public Schools for Carver, but Green Dot officials said their outreach efforts at Fairley High School were more successful and chose to run that school instead. The episode left Carver with negative press but no new help.

Each time, the school’s advocates have breathed a sigh of relief when the school was removed from the chopping block, assured that the school that had been open since 1957 would survive.

But the school’s difficulties deepened over this period, as well, as it dropped to the fourth-lowest-performing in Tennessee according to the state’s rankings. Enrollment fell from 700 students a decade ago to fewer than 200 now, according to district officials, and the school found it hard to hold on to teachers.

The neighborhood saw its population decline during this time, but the uncertainty over Carver’s future also prompted students to transfer or not enroll, White said. Community organizer and former Memphis City Schools board member Sara Lewis pointed to an even broader effect of the repeated referendums on Carver’s existence.

“It just contributes to the further decline of the community,” she said. “And children think we as a community don’t really care about them.”

Superintendent Dorsey Hopson told school board members that the school is in such dire straits that there would be little value in keeping it open.

“The conditions over there in regard to the low enrollment and the constant turnover just make it a very difficult situation for anybody to thrive in,” Hopson said during the April meeting. “I would even say that the faculty there is really doing the best they can with what they have.”

The school’s 16 teachers, who would have to find new positions within the district or lose their jobs, have not participated in the public protests. Neither has Principal Alvin Harris, although he attended the most recent hearing, which drew about 200 people earlier this month. (Harris did not return a request for comment.)

Instead, support for the school has come mostly from the community leaders who have been at Carver’s side each time it was threatened. The George Washington Carver High School Alumni Association put together a community plan that represents the most specific set of suggestions community partners have come up with since the closure attempts started, White said.

The plan includes a proposal to expand Carver’s enrollment zone to include some territory that was rezoned to Hamilton High School when another area high school closed. It also plans for alumni, business leaders, and nonprofit partners to supply academic tutoring and reopen a family resource center at the school. And it urges Hopson to add Carver to the iZone.

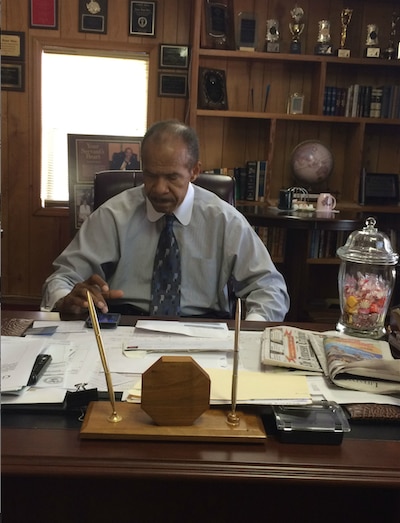

Until he hears Hopson’s answers to the community plan this week, White said he’s still prepared to keep up the fight.

“It’s an ongoing effort,” he said. “We’re sleeping in our battle clothes.”

At the school’s recent community meeting on the proposed closure, school board member Shante Avant, whose district includes Carver, commended community members for supporting the school but noted that more alumni than current parents or students had spoken out.

She suggested that community members would do well to back the board’s plan to move Carver students to Hamilton High School, which is getting extra resources already as part of the district’s iZone and would get even more to support the new students.

“History is important,” Avant said. “But we have to think of the future of our children who are currently here.”