Tennessee education officials allowed students and teachers to go ahead with a new online testing system that had failed repeatedly in classrooms across the state, according to emails obtained by Chalkbeat.

After local districts spent millions of dollars on new computers, iPads, and upgraded internet service, teachers and students practiced for months taking the tests using MIST, an online testing system run by North Carolina-based test maker Measurement Inc.

They encountered myriad problems: Sometimes, the test questions took three minutes each to load, or wouldn’t load at all. At other times, the test wouldn’t work on iPads. And in some cases, the system even saved the wrong answers.

When students in McMinnville, a town southeast of Nashville, logged on to take their practice tests, they found some questions already filled in — incorrectly — and that they couldn’t change the answers. The unsettling implication: Even if students could take the exam, the scores would not reflect their skills.

“That is a HUGE issue to me,” Warren County High School assistant principal Penny Shockley wrote to Measurement Inc.

The emails contain numerous alarming reports about practice tests gone awry. They also show that miscommunication between officials with the Tennessee Department of Education and Measurement Inc. made it difficult to fix problems in time for launch.

And they suggest that even as problems continued to emerge as the test date neared, state officials either failed to understand or downplayed the widespread nature of the problems to schools. As a result, district leaders who could have chosen to have students take the test on paper instead moved forward with the online system.

The messages span from October until Feb. 10, two days after the online test’s debut and cancellation hours later. Together, they offer a peek into how Tennessee wound up with a worst-case scenario: countless hours wasted by teachers and students preparing for tests that could not be taken.

October: ‘Frustration … is definitely peaking’

Leaders with the Education Department, local districts and Measurement Inc. all knew that Tennessee’s transition to online tests wouldn’t be easy. So the test maker and the department developed a plan to identify weaknesses: stress tests they called “Break MIST” to tax and troubleshoot the online system.

They all had a lot riding on a smooth rollout. Tennessee was counting on the scores to assess whether students are measuring up to new and more challenging standards, to evaluate teachers, and to decide which schools to close. Districts, even the most cash-strapped, had invested millions of dollars on new technology. And Measurement Inc., a small company headquartered in Durham, was looking to prove that it belonged in the multibillion-dollar testing industry’s top tier.

The first “Break MIST” day on Oct. 1 was a mess — as expected. Students in the eastern part of the state logged on without issue, but the system stumbled as the majority of students started their tests an hour later.

That morning, emails show that Measurement Inc. received 105 calls reporting problems. The company noted particular problems in districts using iPads. Officials from the testing company assured the state that the bugs could be fixed, and the education department passed the message on to the public.

Department officials said nearly 1.5 million practice tests were completed successfully over the course of the fall. But emails show that even on days that weren’t meant to tax the system, problems emerged.

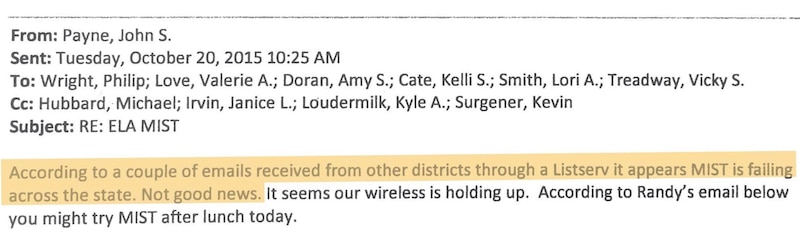

On Oct. 20, students in some districts were taking practice tests when “everything quit,” according to a state official who summarized complaints that local technology coordinators were swapping by email.

“Not very reassuring,” wrote Randy Damewood, the IT coordinator in Coffee County.

“Not good news,” agreed John Payne, director of technology for Kingsport City Schools, who suggested that his own district’s tests were working that day.

“The frustration among teachers and central office staff is definitely peaking,” wrote Eric Brown, a state official.

But there was more frustration to come, much of it behind the scenes at the Education Department.

December to January: Communication falters

Even after Measurement Inc. and department officials worked together to address problems during practice tests, the department still wasn’t confident in the online system. They weren’t sure whether problems were due to local infrastructure or something bigger. Officials planned two more “Break MIST” days in January to find out.

But they didn’t involve Measurement Inc. in the planning, at least according to company officials who wrote to the department to say they learned of those plans only after being copied on an email sent to local superintendents by Education Commissioner Candice McQueen.

That message was one of many in which officials with the state or the testing company expressed frustration about communication in the weeks leading up to the testing period.

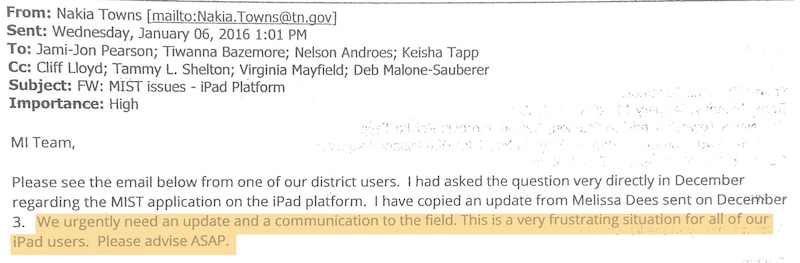

One tense exchange dealt with the problems faced by students taking practice tests on iPads. “Will the iPad platform be ready for primetime in the spring?” Assistant Commissioner Nakia Towns asked Measurement Inc. officials on Dec. 3. “I feel like we need to be honest on this one.”

The test maker did not email a response, and Towns raised the issue again a month later and indicated that she was still waiting for an answer. “I had asked the question very directly in December,” she wrote Measurement Inc. on Jan. 6. “We urgently need an update.”

It took five more days, until Jan. 11, for her to get an answer. A reply from a Measurement Inc. testing expert blamed the problem on Apple but suggested the company had a “workaround.”

The next day, 504 students in Dyer County, about 80 miles north of Memphis, attempted to take the exam, many of them using iPads. Not one was able to complete the test because questions took too long to load, according to a report from Measurement Inc.’s call center. (Another half-million tests were completed successfully during January, according to department officials.)

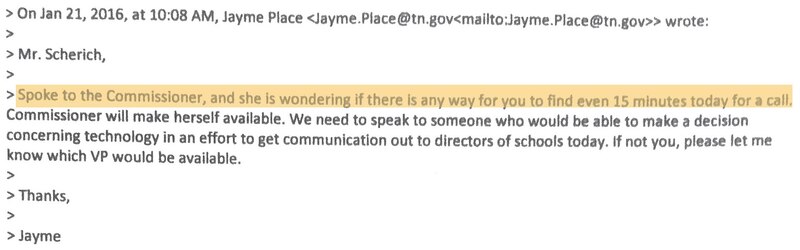

In an interview this week, McQueen told Chalkbeat that Measurement Inc. never fixed the iPad problem and that state officials called Apple themselves looking for a solution. She was still looking for an answer on Jan. 21, when she tried to speak directly with Measurement Inc. President Harry Scherich.

“She is wondering if there is any way for you to find even 15 minutes today for a call,” McQueen’s chief of staff wrote. “Commissioner will make herself available. We need to speak to someone who would be able to make a decision concerning technology in an effort to get communication to directors of schools today.”

Scherich, who was in Michigan meeting with that state’s education department, initially said he did not have time to speak with McQueen. (Measurement Inc. is one of two companies producing Michigan’s new exam.) Later that day, he agreed to speak.

McQueen said she and her team came to a conclusion the next day: The test wouldn’t work on iPads. They emailed and called districts that had purchased tablets for testing and recommended a switch to paper.

February: A last-minute warning gets too little attention

Even as tensions mounted and glitches piled up, both the department and Measurement Inc. projected confidence about what would happen on Feb. 8, when the test would go live for most Tennessee schools. State officials even invited reporters to Department of Education offices on Feb. 3 to say they were optimistic about the rollout.

But behind the scenes, they were preparing for the worst. McQueen asked the test maker’s call centers to prepare for a major outage, something a Measurement Inc. employee told her was “very unlikely.”

She also emailed districts telling them they should consider switching to paper tests if their students were waiting too long for questions to load. She gave them three days to decide.

Just 15 of Tennessee’s nearly 150 districts took her up on the offer, McQueen told Chalkbeat.

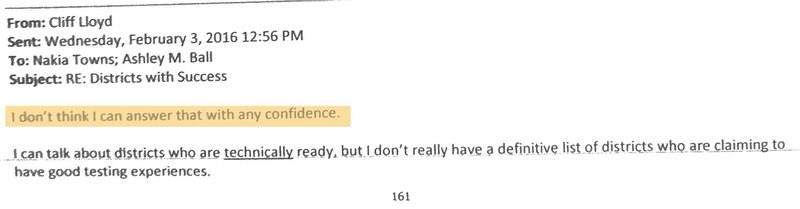

But emails show that the state knew that most districts were having difficulties. When one district’s technology coordinator asked the state for a list of districts ready for the online exam, officials came up short.

“I don’t think I can answer that with any confidence,” the department’s top technology officer wrote.

Five days later, on Monday, Feb. 8, the test officially began. Again, the system handled the first set of test takers but broke down when the rest of the state’s students logged on.

As students stopped being able to connect or saw their tests freeze, emails show that technology directors began frantically contacting each other.

“Has anyone else had MIST drop out on them?” the director from Houston County Schools asked. A chorus of technology directors from other districts replied in the affirmative.

Within hours, Tennessee had ended its foray into online testing. First, McQueen told districts to suspend the exams, then directed them to give up on the online platform altogether.

“We are not confident in the system’s ability to perform consistently,” she wrote in an email to school superintendents that afternoon.

McQueen told Chalkbeat that officials started the day “in good faith,” with an assumption that Measurement Inc. had resolved problems adequately. Scherich told Chalkbeat that he’s still unconvinced that the problems were the company’s fault. He suggested that Tennessee’s decision to cancel testing came too soon.

Either way, the department’s top technology official put it simply when he emailed McQueen on the day of the failure. “It appears that greater procedural and operational rigor could have prevented the network outage,” Cliff Lloyd wrote to McQueen.

The debacle was just what Ravi Gupta, the CEO of a Nashville-based charter school, was worried about when he pressed the state in January for more transparency about the status of the online platform.

“It would be a betrayal of our students’ hard work if adult technical failures stood in the way of their success,” Gupta wrote to McQueen.

In the end, that’s exactly what happened.

Clarification (June 28, 2016): This story has also been revised to clarify the impact of the department’s communications on district testing decisions. It has also been updated to include new information about successful practice tests.