The sign outside says Westhaven Elementary School, but those who enter are immediately reminded that Shelby County Schools’ newest school building is home to three communities.

Forming a giant “W” at the entrance are the names Westhaven, Fairley and Raineshaven — a symbol of unity sought this fall when the district consolidated three elementary schools into one.

It hasn’t been a seamless merger. Members of the Westhaven community initially protested the shuttering of their school, fearful that district leaders wouldn’t follow through with their promise to build a new one in its place. And students and faculty had to be relocated temporarily to Fairley and Raineshaven during construction.

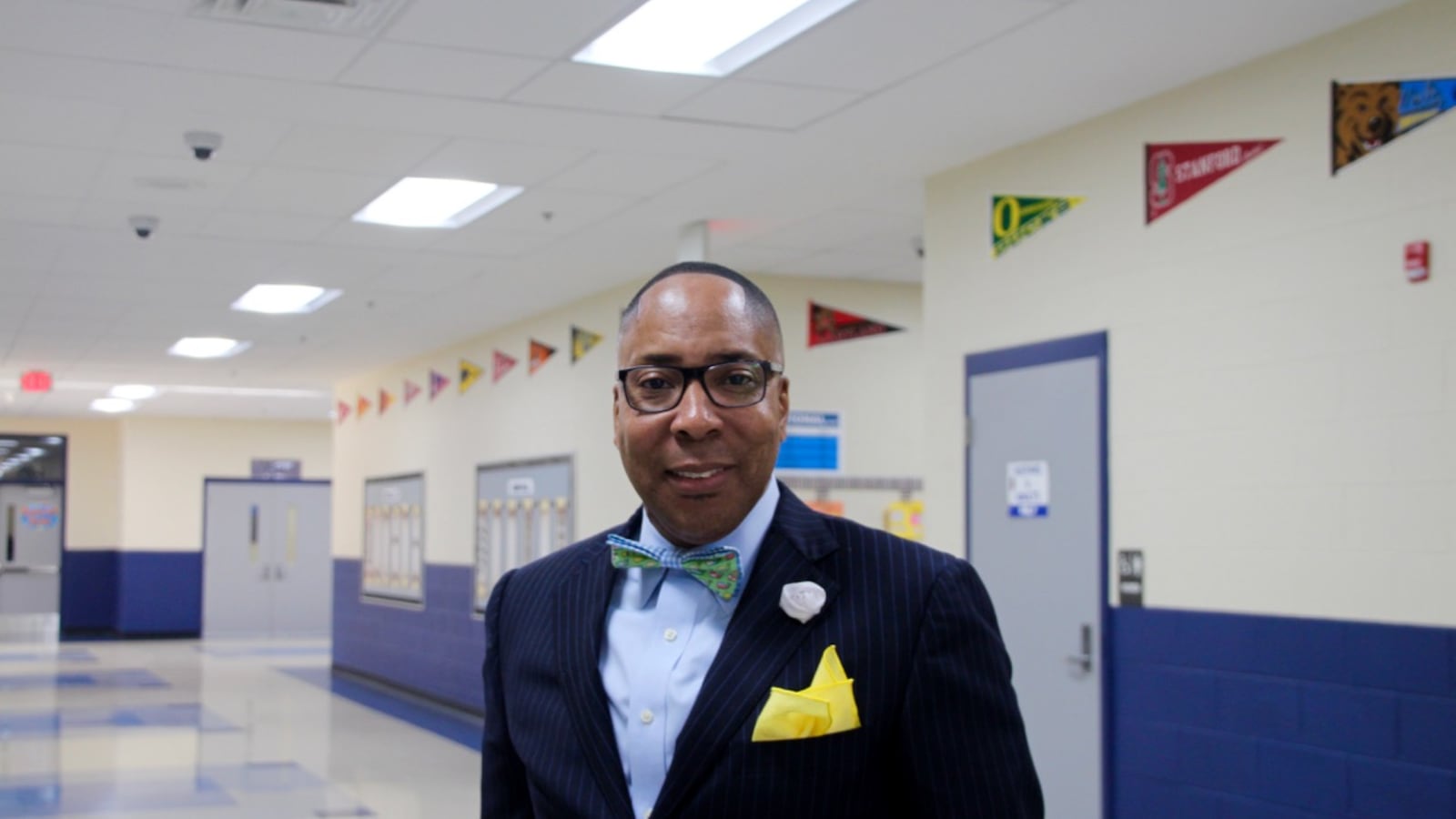

But now that Westhaven’s glitzing new $14 million building is open — and Fairley and Raineshaven have been closed, with their students shifted to Westhaven — Principal Rodney Rowan is working to fuse three communities into one. The goal is to create a different pathway to academic bliss.

It’s a model that Memphis is watching closely as leaders look to shutter more under-enrolled schools in old buildings that are expensive to maintain. In the process, they want to place their students in improved learning environments where they can be more successful.

In November, Superintendent Dorsey Hopson proposed three similar building and consolidation projects. His plan would replace three schools, close five others, and consolidate the students. The model would give families the promise of being part of something new, unlike unpopular school closures in the past that have sent students to old rival schools.

Read more of our coverage on past Memphis school closures.

Hopson has hailed Westhaven as the emerging model for a district seeking to address challenges with academics, enrollment and aging buildings. As such, his administration turned to Rowan, a go-to principal with a track record of success, to shepherd the rebooted school.

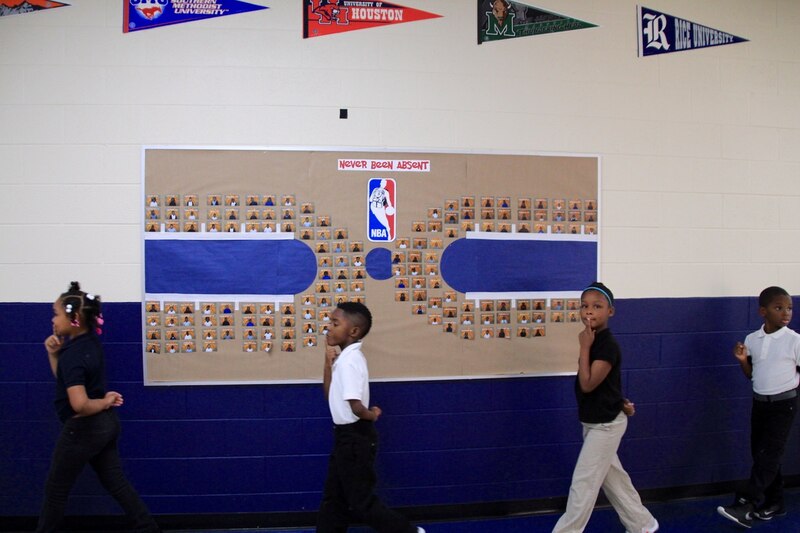

Walking through his new stomping grounds, Rowan is quick to point out large bulletin boards in the hallway trumpeting students with good scores and perfect attendance. Those students will be rewarded with a popcorn party, just one of the school-wide celebrations that Westhaven holds each month to incentivize students — and to build community.

“We had a Thanksgiving program where students performed,” Rowan said. “We have a Motown Christmas this year. A Grandparents Day luncheon. Muffins for Moms. Doughnuts for Dads. Coffee dates with me, where parents are able to tell me what they like and what they want different. … To create culture, you’ve got to have activities that create ownership.”

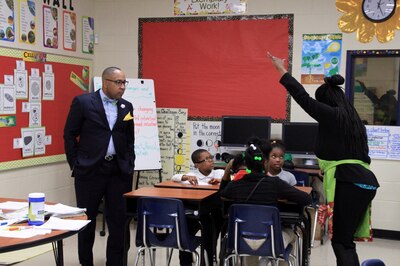

As Shelby County Schools looks to build, close and consolidate more schools, Rowan has advice for those incoming principals. For instance, it would have been a mistake, he said, to discount the staff and cultures at Fairley and Raineshaven when launching a consolidated Westhaven. So he hired some familiar faces, which did a lot to build trust among parents and students.

“You can’t throw baby out with the bathwater,” Rowan said. “You have to take into consideration how things were done at previous schools.”

Rowan came from Cherokee Elementary, where he was principal of a low-performing school that saw significant test score gains under his leadership. Like Cherokee, the new Westhaven is now part of Shelby County Schools’ Innovation Zone, a school turnaround initiative that gives principals greater autonomy to hire and fire staff, pay teacher bonuses, overhaul curriculum, and extend the school day.

Of the three new school consolidations proposed by Hopson, only Alcy is recommended to shift to the iZone.

Either way, Rowan warns that this kind of work is not for the faint of heart. He routinely puts in 60- to 70-hour weeks.

“You’ve got to know you’re going to have no life the first year if the school’s going to run the way you want it,” Rowan said of his 800-student school. “And the people you hire must understand you work until work is done. Lots of our teachers come in on Saturdays and holidays, because they want to get the work done.”

Whether the build-close-consolidate plan could work in other communities is yet to be seen. However, the school board has given Hopson the first green light for more such projects and will cast their final vote early next year. In the meantime, board members are talking with their constituents and studying the details.

One lesson learned from from Westhaven: Closing and demolishing a school to build a new one in its place is disruptive, according to Shante Avant, a school board member representing Westhaven. Under the new proposal, the district would build new schools on other parts of the existing campuses so that schools don’t have to close during construction.

Still, Avant cautions that a “pull out of the box” model won’t work everywhere.

“Every community is different, so the needs are different. But we learned a lot with Westhaven about how to build trust,” Avant said. “And there are some lessons that are replicable in any situation, like having a strong leader who will hire the staff needed. Mr. Rowan had a vision in mind when he came in.”

The vision is working so far for Tina Isaac, whose 7-year-old daughter came to Westhaven this year from Raineshaven.

“I can tell she’s doing better and it seems like the teachers just have a lot of support,” Isaac said. “We weren’t too sentimental leaving Raineshaven, and it helps we don’t have to travel further to go to this school.”