As teacher Nikki Wilks looked around at her Memphis classroom on Wednesday, her high school students seemed to reflect the divide in the nation itself.

One student, who is black, said she worried about raising her 3-year-old daughter in a nation led by President-elect Donald Trump — a world, she imagines, where she won’t be able to speak her mind about racism or inequality. She told Wilks that she needed a hug.

Another student came in wearing a “Make America Great Again” cap, unfazed by or unaware of the anguish felt by many students in a school with a significant Hispanic population, a frequent target of Trump’s campaign rhetoric.

Wilks, who had supported Hillary Clinton, admitted to being shell-shocked. She was in and out of tears all morning as she tried to teach her 12th-grade English classes at Kingsbury High.

“The classes are much more somber than normal,” Wilks said. “It feels somewhat like everyone is walking around on eggshells, scared that if we actually vocalize it, we are making it more real, more permanent.”

Across the country, educators of all political persuasions tried to offer space for students to process the surprising Election Day results, in which Clinton won the national popular vote but Trump won the White House. At schools in New York, Colorado, Indiana, and Tennessee, school leaders scrambled to react to the news before Clinton had even given a concession speech.

And in the wake of a campaign in which Trump talked about ramping up deportations, building walls, and banning Muslims from entering the country, teachers at schools that serve immigrants and their families faced intensely personal questions. Will I be forced to leave? Will my parents?

Kevin Kubacki, who runs the Neighborhood Charter Network in Indianapolis, recalled a young student from Brazil asking teachers last year if she could form a club encouraging families not to vote for Trump. She didn’t want her friends from Mexico to have to leave, she said.

“For us, this very real,” he said. “Today, our students have a lot of questions and a lot of fears.”

In an early morning huddle, staff members at a Neighborhood school talked about using lessons about the three branches of government to remind students how no one person has ultimate power in America. Staffers also plan to ask a lawyer to meet with parents concerned about their immigration status, Kubacki said.

In the Denver suburb of Aurora, Principal Ruth Baldivia said she heard of two incidents Wednesday in which students were “not being nice to their fellow Mexican students,” telling them they will have to leave the country.

And at Rocky Mountain Prep, a charter network with two elementary schools in Denver, CEO James Cryan said a number of students asked if the election result means that they’ll no longer have a home in the U.S., “or expressed concerns about a specific relative, asking if their father or mother will have to move away.”

Experts say Trump’s vision of an America rid of people who are currently here illegally would be expensive and time-consuming to achieve. But Trump will have wide latitude to quickly roll back the protections that President Obama extended to undocumented immigrants who are law-abiding and who came to the country as children with their families.

In Queens, New York, a ninth-grader named Kevin who came to the U.S. one year ago from Argentina said his immigrant classmates at Newcomers High School arrived to class full of worry.

“They were saying that they could be deported,” he said.

Even before students arrived, educators were grappling with how best to handle the news.

Sarah Scrogin, principal of New York’s Bronx Academy for the Future, woke up Wednesday morning and wondered: When roughly 70 percent of her students are Hispanic, and many have friends or relatives who could face the consequences of Trump’s harsh stance on immigration, could teachers simply carry on with normal activities? On the other hand, would it be appropriate for teachers to share their own political views as a way of comforting students — or themselves?

“Our job as educators is not to tell others what to think,” she wrote in a morning email to staff, “but rather, to work together with young people to develop their own critical thinking.”

Christine Montera, who teaches Advanced Placement U.S. History, got that email and arranged her classroom’s desks into a circle for students to talk. Opinions in class varied: One student, Carla Borbon, said she was concerned for LGBT people “because this man is homophobic,” she said. “A lot of people were wondering what is going to happen to them.”

Junior Hugo Rodriguez had a different take. “I was annoyed about things people were saying about Donald Trump, saying that he’s a rapist and wanted to deport everyone — that’s not true,” he said. “I actually don’t mind Trump as president.”

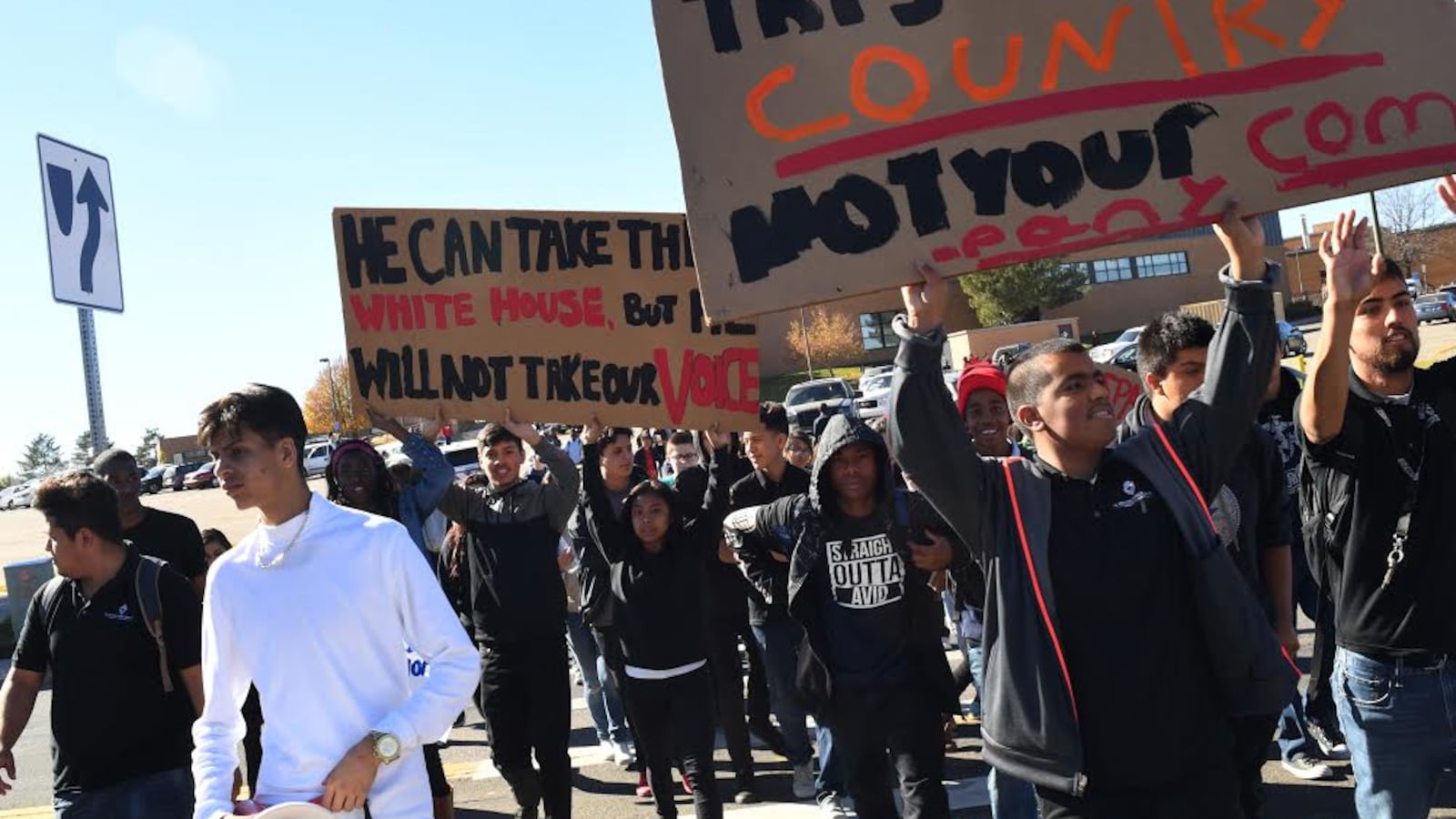

Exit polls show that America’s youngest voters were more likely to have voted for Clinton on Tuesday. On Wednesday, many were determined to make their voices heard in other ways.

In Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, dozens of high school students walked out of class in protest of Trump’s victory. At Denver’s Noel Community Arts School, district leaders invited reporters to an impromptu assembly, where students spoke of their frustration. Some sang “Hallelujah.”

Senior class president Peter Lubembela was one of the speakers. A Congolese refugee who was born in Tanzania, he came to the United States when he was 7.

This morning, Lubembela said he was ready to move forward. “We have to empower ourselves and work harder than before and prove all these stereotypes wrong,” he said.

Melanie Asmar, Eric Gorski, and Yesenia Robles contributed reporting from Denver, Shaina Cavazos and Dylan McCoy from Indianapolis, Caroline Bauman from Memphis, and Christina Veiga and Alex Zimmerman from New York City.