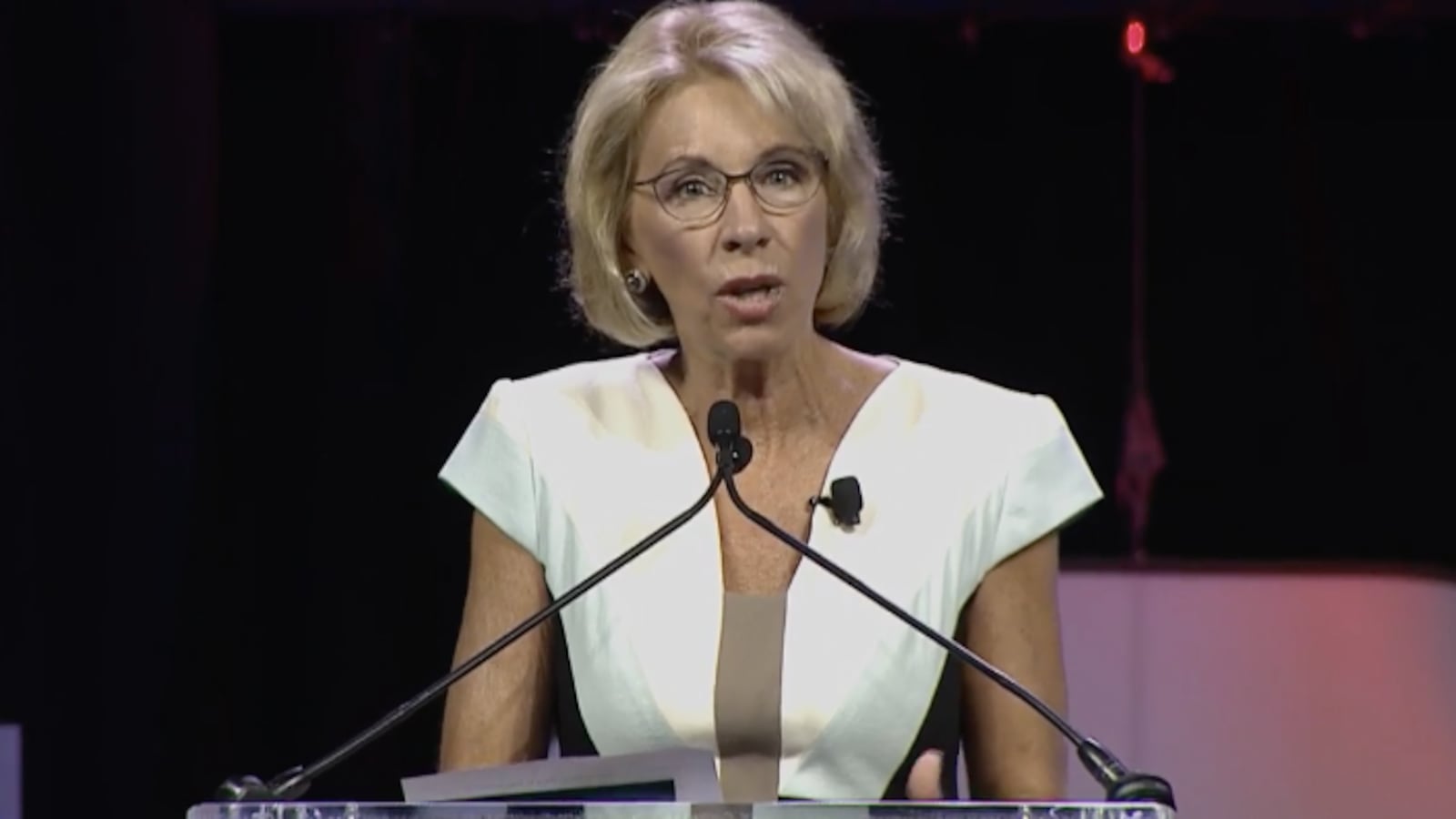

In an address to charter school advocates, leaders, and teachers in Washington D.C., U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos appeared to chide charter supporters who oppose her push to expand private school choice.

She also criticized rules designed to ensure charter quality, but that — in her telling — had turned into red tape, stifling innovation.

“Charters are not the one cure-all to the ills that beset education,” she said at the conference of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. “Let’s be honest: there’s no such thing as a cure-all in education.”

Her remarks hinted at growing divides within the school choice movement. Charter school advocates in New York, California, and Denver have been cool to the idea of expanding vouchers. The broader group has splintered on other issues, too: accountability for charter schools, for-profit charters, President Trump’s budget, and issues beyond education.

On the question of how to measure school quality, DeVos continued to send mixed messages. On the one hand, she praised the National Alliance for having “proven that quality and choice can coexist.” On the other hand, she criticized efforts to ensure that schools are high-quality through “500-page charter school applications.”

This touches on a longstanding debate about how much regulation charter schools need — and who should provide it.

Research released earlier this week showed that there is significant variation in test score performance among different charter school networks, and that for-profit and virtual schools lag behind. DeVos has supported both types of schools.

“A system that denies parents the freedom to choose the education that best suits their children’s individual and unique needs denies them a basic human right,” said DeVos. “It is un-American, and it is fundamentally unjust.”

Other research has found that when charter schools are closed because of poor performance, student achievement increases. Yet market-oriented choice advocates often suggest that parents are in the best position to decide which school is a good fit for their child, and test scores shouldn’t be the sole basis for those decisions.

When asked during a brief question and answer session with Derrell Bradford — a supporter of school choice from the group 50CAN — where she stood, DeVos did not offer a specific answer.

“Our focus should be on not choice for choice’s sake, but choice because parents are demanding something different for their children,” she said. “For every year that they don’t have that opportunity, their child is missing out.”

Amy Wilkins, a vice president for the National Alliance, said that if a charter school is not meeting academic performance goals, “it should absolutely close,” though emphasized that the process should be done carefully with the needs of parents in mind.

She sees DeVos’s position as slightly different than her group’s.

“My sense is she’s probably a little more on the ‘choice for choice’ [side] than the Alliance is,” Wilkins told Chalkbeat.

Greg Richmond, the head of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers and a prominent advocate for holding charter schools accountable for their academic results, said in an interview that he wasn’t sure of DeVos’s position on the topic.

“Clearly we’re in the robust accountability camp,” he said in an interview. But of DeVos, “I haven’t figured [DeVos] out yet.”

In her speech, DeVos also referenced a recent blog post by Rick Hess, of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, whom she called a friend. “Many who call themselves ‘reformers’ have instead become just another breed of bureaucrats – a new education establishment,” she said.

Although she spoke passionately about helping low-income students escape struggling schools, DeVos only briefly mentioned President Trump’s proposed budget cuts, the brunt of which critics say would fall on poor students and their families.

“While some of you have criticized the President’s budget – which you have every right to do – it’s important to remember that our budget proposal supports the greatest expansion of public school choice in the history of the United States,” DeVos said. “It significantly increases support for the Charter School Program, and adds an additional $1 billion for public school choice for states that choose to adopt it.”

Some charter school teachers say the budget would hurt their students.

“It’s really disturbing that the same people she’s claiming she wants to help and be an advocate for are the one’s that she’s hurting,” said Carlene Carpenter, a charter school teacher in Chicago and a member of the American Federation of Teachers. “We’re hearing one thing, but in actuality what’s really happening with these budget cuts is the after-school programs are being eliminated.”

The cuts are still a proposal, and conventional wisdom in D.C. is that the plan has no shot at getting through Congress.

DeVos reiterated her view that money is not the key to improving schools, though recent research suggests more resources do in fact help schools get better. She also agreed with the idea that charter schools are not equitably funded.

DeVos’s remarks come as the National Alliance toes a careful line. The group’s president, Nina Rees, addressed that head-on in remarks on Monday.

“Let me tackle the big elephant in the room,” she said. “Donald Trump.”

“We can disagree with President Trump and disagree loudly when we believe it’s the right thing to do, but to ignore the impact of a big increase in funding at the federal level would be irresponsible,” Rees said. “It would put the interest of adults and political activists ahead of the needs of our schools.”

Rees has faced pressure from some charter school leaders after a number of them wrote an op-ed in USA Today criticizing the Trump budget. The National Alliance initially offered unmitigated praise for the proposal, though has since criticized aspects of it.

“Accepting the president’s agenda on charter schools doesn’t connect us to his full agenda,” Rees said.