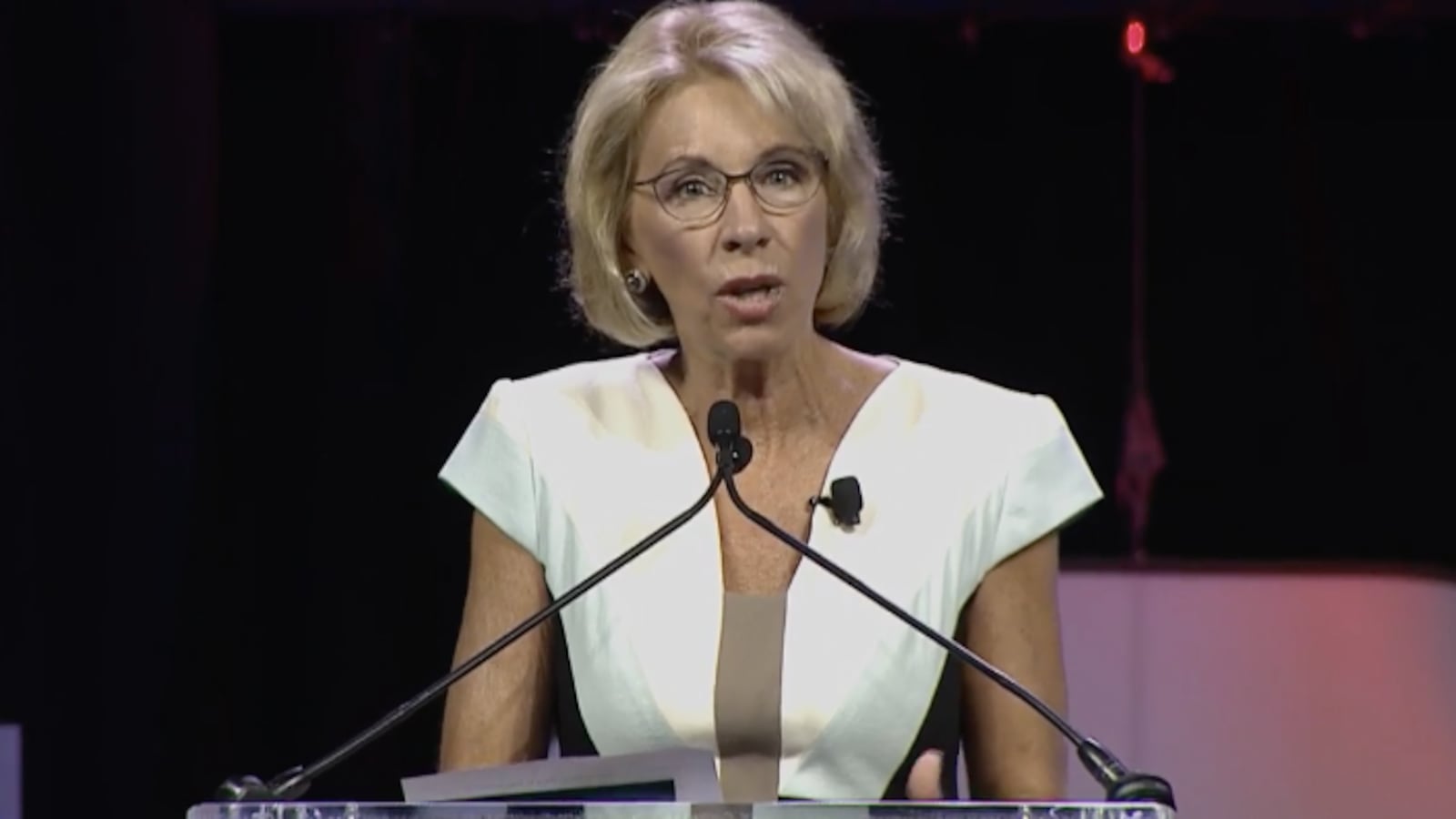

If Betsy Devos is paying any attention to unfolding critiques of virtual charter schools, she didn’t let it show last week when she spoke to free-market policy advocates in Bellevue, Washington.

Just days after Politico published a scathing story about virtual charters’ track record in Pennsylvania, DeVos, the U.S. education secretary, was touting their successes at the Washington Policy Center’s annual dinner.

DeVos’s speech was largely identical in its main points to one she gave at Harvard University last month. But she customized the stories of students who struggled in traditional schools with local examples, and in doing so provided an especially clear example of why she believes in virtual schools.

From the speech:

I also think of Sandeep Thomas. Sandeep grew up impoverished in Bangalore, India and experienced terrible trauma in his youth. He was adopted by a loving couple from New Jersey, but continued to suffer from the unspeakable horrors he witnessed in his early years. He was not able to focus in school, and it took him hours to complete even the simplest assignment. This changed when his family moved to Washington, where Sandeep was able to enroll in a virtual public school. This option gave him the flexibility to learn in the quiet of his own home and pursue his learning at a pace that was right for him. He ended up graduating high school with a 3.7 GPA, along with having earned well over a year of college credit. Today, he’s working in finance and he is a vocal advocate for expanding options that allow students like him a chance to succeed.

But Thomas — who spoke at a conference of a group DeVos used to chair, American Federation for Children, in 2013 as part of ongoing work lobbying for virtual charters — is hardly representative of online school students.

In Pennsylvania, Politico reported last week, 30,000 students are enrolled in virtual charters with an average 48 percent graduation rate. In Indiana, an online charter school that had gotten a stunning six straight F grades from the state — one of just three schools in that position — is closing. And an Education Week investigation into Colorado’s largest virtual charter school found that not even a quarter of the 4,000 students even log on to do work every day.

The fact that in many states with online charters, large numbers of often needy students have enrolled without advancing has not held DeVos back from supporting the model. (A 2015 study found that students who enrolled in virtual charters in Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin did just as well as similar students who stayed in brick-and-mortar schools.) In fact, she appeared to ignore their track records during the confirmation process in January, citing graduation rates provided by a leading charter operator that were far higher — nearly 40 points in one case — than the rates recorded by the schools’ states.

She has long backed the schools, and her former organization has close ties to major virtual school operators, including K12, the one that generated the inflated graduation numbers. In her first week as education secretary, DeVos said, “I expect there will be more virtual schools.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the location of the dinner.