When Betsy DeVos returned to the advocacy group she used to lead last week, she told attendees to push for systems where students could attend any kind of school.

Traditional, charter, religious, and virtual schools should be options for students, the education secretary argued, as should “an educational setting yet to be developed.”

“Our current framework is a closed system that relies on one-size-fits-all solutions,” DeVos said. “We need an open system that envelops choices and embraces the future.”

This vision was clear throughout the American Federation for Children summit: that schools need to be reinvented with an emphasis on technology. And throughout the gathering, exclusively online schools were a key part of that vision — even though some supporters acknowledge existing virtual schools have not produced strong academic outcomes to date.

Advocates say that online schools have the potential to harness “personalized learning,” a term that generally means using technology to provide an education tailored to each student’s needs.

“The end game … is personalized learning,” said Kevin Chavous, a board member and executive counsel at AFC, in response to a question about virtual schools. “We are going to get to this place where as opposed to every child being shepherded into a schoolhouse where they sit in a classroom and where a teacher stands and delivers, and then they regurgitate back … those days are not going to be the future.”

This belief in personalized learning dovetails with the focus at another recent conference of education reformers, the New Schools Venture Fund summit. But AFC’s emphasis on exclusively virtual schools appears distinct, and comes as online charter schools have endured a wave of negative press and research studies.

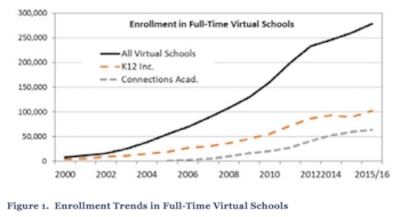

In addition to advocating for school vouchers, DeVos has also long backed virtual schools, a small but swiftly growing sector of schools.

For-profit virtual school companies are tightly connected to AFC. The two largest such groups, K12 and Connections Academy, were among the chief sponsors of the conference. Chavous is a K12 board member, and John Kirtley of AFC praised the company, saying, “They’re doing great things in digital learning.”

And although the research evidence for blended or personalized learning models is mixed, the handful of studies of fully virtual schools point to a clearer verdict: students in such schools perform dramatically worse on standardized tests relative to similar students in traditional schools, according to a study of thousands of virtual charter school students in 18 states.

Advocates acknowledged that the research to date has shown that cyber-charter schools have produced dismal test score results, but said that they are good fits for some students and are improving over time.

Chavous did not dispute the negative research findings, but suggested that students who remained in virtual schools for several years saw academic gains. (The widely cited national study of online charter schools did not examine this question, but did show that about 75 percent of students had left their online school within four years.)

K12 as an organization has challenged the recent research, saying it does not sufficiently control for differences between students in virtual schools and those in brick and mortar ones, a point some outside researchers say is a real limitation of existing studies.

Robert Enlow of the group EdChoice described the research on virtual schools as “not great, at the moment,” but pointed out that studies rely on test scores, a limited measure in his view. (EdChoice is a funder of Chalkbeat.) Enlow said that he had seen evidence that online schools could improve life outcomes for students in a presentation from K12.

The results from research and negative press have led some charter school advocacy groups to argue for stricter regulation of online charter schools. EdChoice and AFC did not join this push and K12 rejected the recommendations out of hand.

“The device of making a school virtual — I think we need to preserve the tool,” said Derrell Bradford of the 50-state Campaign for Achievement Now, or 50CAN, which was part of the statement calling for tighter oversight. “At some point, someone’s going to figure out a way to do virtual well.”

Graph from the National Education Policy Center.