Who benefits most from private school voucher programs: families with few options or the schools themselves?

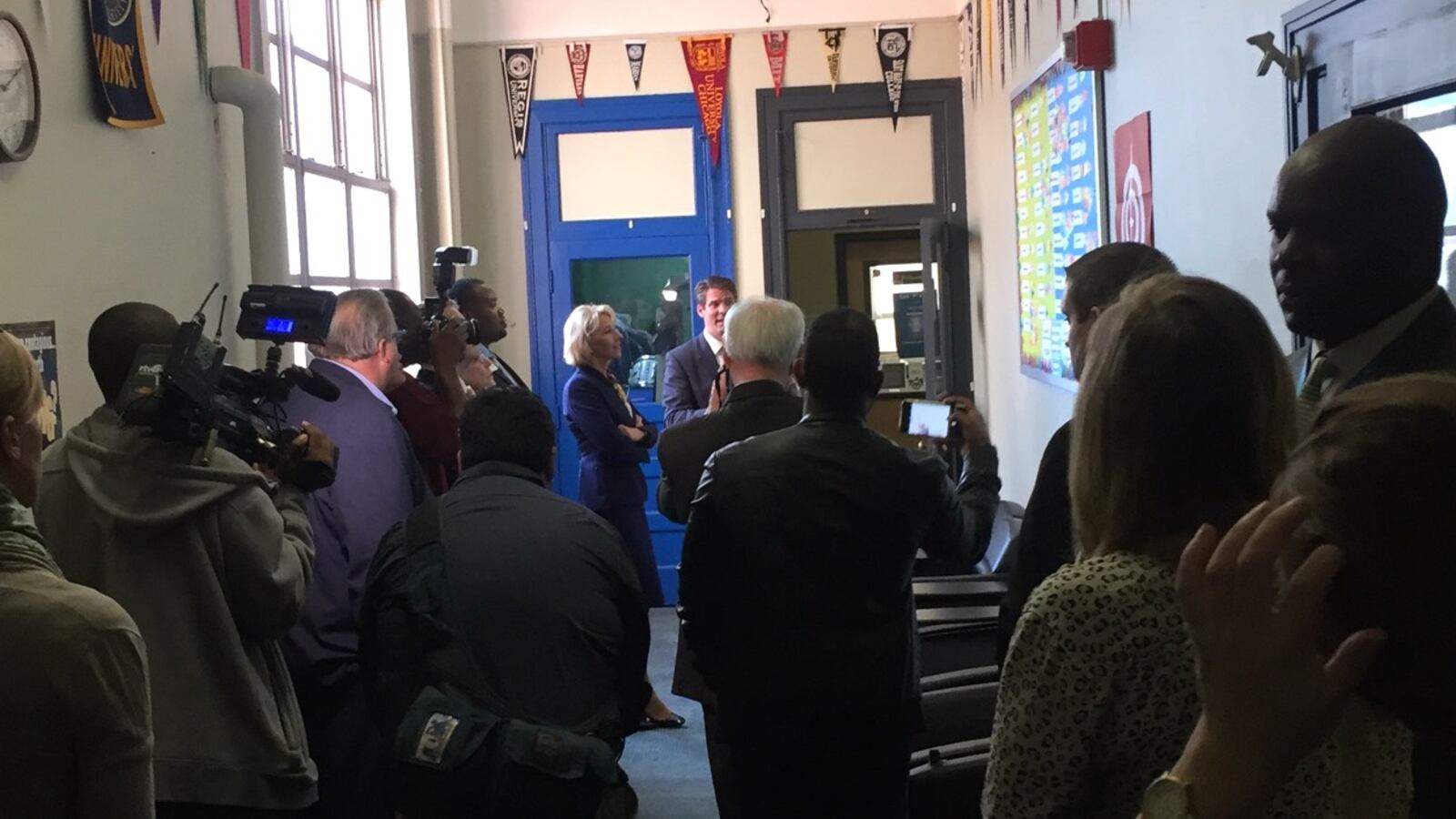

This is a hotly debated question among supporters and critics of school vouchers, and is especially relevant as U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has vowed to allow more families to use public dollars to pay for private school tuition.

A 2016 study considers this question and comes back with an answer: It depends. Programs targeted at certain students, like low-income ones, lead to an increase in private school enrollment; but universal choice programs with few if any eligibility requirements don’t cause more students to enter private schools, with schools instead raising tuition.

That’s the conclusion of the research, published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Public Economics, which examined eight private school choice initiatives, including both voucher programs and tax credit subsidies, which offer generous tax breaks for private school fees.

The researchers, Daniel Hungerman of Notre Dame and Kevin Rinz then at the National Bureau of Economic Research, divide the programs into two categories: what they refer to as restricted and unrestricted. Restricted programs limit availability to certain students, such as those who are low-income or have a disability; unrestricted programs are open to everyone.

An example of a restricted program is Florida’s tax-credit program, which incentivizes donations to nonprofit groups that offer tuition scholarships to low- and middle-income families. Arizona’s tax-credit initiative is similar in structure, but is classified as unrestricted because it is open to all students. (Arizona also has tax credit programs targeted at low-income students and those with disabilities.)

The study then looks at how the two types of programs affect school enrollment and finances, using data from tax returns of thousands of private schools.

Restricted-choice programs cause large increases in the number of students attending private school. But “programs that offer unrestricted subsidies lead to price increases but no change in enrollment,” the authors conclude.

In other words, under the universal programs studied, private schools did not admit additional students, but did raise tuition — by an amount the researchers estimated to be roughly the same as the public subsidy. (It’s possible that different — just not more — students enrolled as a result of the choice program.)

This gives credence to concerns that untargeted programs fail to create additional access to private schools, but are a revenue boon for schools.

At the same time, targeted programs seem to have their intended effect of allowing more families to choose private school. (Of course, whether that ends up helping students academically remains the subject of much debate.)

This suggests that school choice advocates who want to expand enrollment in private schools — as opposed to simply allowing them to raise tuition — should favor targeted programs. Some choice supporters have recognized this concern, recommending the creation of education savings accounts, which give families a pot of money to spend on any combination of educational expenses. Anna Egalite, a professor at North Carolina State University, argues that this approach, unlike traditional vouchers or tax credits, puts “downward pressure” on prices by “encourag[ing] parents to be cost conscious.”

DeVos and the Trump administration have not released any details on their promised school choice plan, but some past federal proposals have been focused on low-income student, and most existing state voucher and tax credit programs have restrictions of some sort. However, key school choice groups, including EdChoice and the American Federation for Children, which DeVos used to lead, have supported universal choice policies.

The study is one of the only analyses of how choice programs affect private school enrollment, but it comes with a number of caveats.

The research examined unrestricted programs that offer fairly small subsidies, often significantly less than in voucher initiatives. It’s unclear if the finding — that programs open to all don’t increase private school enrollment — would hold in cases where there were more generous subsidies.

Another caveat: it might be hard to categorize programs with eligibility requirements that most families can meet.

Take Indiana’s voucher program, the largest in the country. The state initially had tight income requirements, limiting the program to poor families; when those rules were in place, private school enrollment rose.

But after the state raised the income threshold to provide partial vouchers to some middle-income families, private school enrollment has essentially flatlined, raising the possibility the school choice initiative hasn’t actually given parents new choices — but simply subsidized existing ones. Since then, the number of students using the program has increased, while the number attending private school without a voucher has dropped precipitously.

It’s impossible to know the effects of Indiana’s voucher program on private school enrollment without a more careful analysis, and the recent study would have categorized it as a restricted program. In recent years many states have seen private school enrollment fall, so the fact that it remained steady in Indiana could be the result of the voucher system.

However, the income requirements in Indiana were more lenient than many of the other programs studied, and over half of students in the state are eligible to receive a voucher.

“At some point the [income] threshold gets so high that the breakdown we offered would not be useful,” said Hungerman, one of the study’s authors.