When the Every Student Succeeds Act won bipartisan support from a famously polarized Congress in 2015, it was less a sign of the two parties’ ability to work together than an indictment of what they were replacing: No Child Left Behind.

NCLB had grown increasingly unpopular, blamed for setting impossible-to-reach goals, inciting test-prep frenzy, and unfairly targeting high-poverty schools. (The law has defenders, too, who point to evidence that it increased student achievement in math and provided important new breakdowns of performance data by race.)

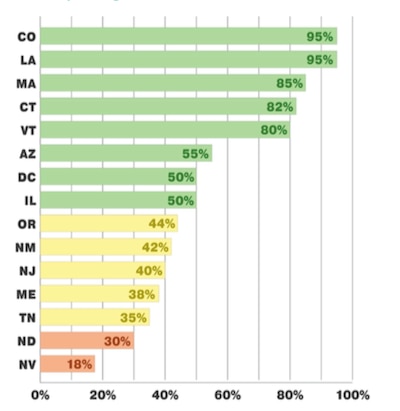

ESSA gave states a chance to start fresh. To date, 16 states and Washington, DC have submitted their plans to implement the law; one plan, Delaware’s, has been approved by the Department of Education.

With some plans in hand, it’s worth asking: Are states really changing course? Are they learning from what many viewed as the problematic aspects of the law ESSA replaced?

Here are some of the sharpest criticisms levied at No Child Left Behind — and what we know about whether states are now planning to go in a different direction.

Criticism #1: States put too much focus on testing.

No Child Left Behind became closely associated with high-stakes testing. ESSA continues to require annual testing in grades three through eight, but allows states to use metrics other than test scores in their plans for evaluating schools.

Indeed, every state that has submitted a plan so far has added — or plans to add — at least one additional measure. The most popular has been chronic absenteeism.

“States are broadening their accountability systems beyond reading and math,” according to a review of state plans by Bellwether Education Partners, an education consulting firm generally aligned with the education reform movement. “Most states added science and a more accurate measure of student attendance, not to mention indicators measuring physical education, art, and school climate.”

But, particularly in elementary and middle school, it remains true that test scores will be the major driver of which schools are deemed low-performing.

That’s partially because the law requires “much greater” weight to be placed on test scores — and on graduation rates for high schools — than on non-academic measures like absenteeism or student engagement.

Still, states have interpreted that in different ways. Delaware’s system will base 70 percent of its ratings for elementary and middle schools on state tests. In Louisiana, 75 percent of scores for elementary schools will be determined by state math and English tests and 25 percent will come from science and social studies exams. (Eventually, Louisiana plans to add “access to a well-rounded curriculum” as a measure, though it will only account for 5 percent.)

Other states are making greater efforts to scale back testing. In Maryland, according to a draft plan, only 45 percent of elementary-school scores will be based on state tests — though it remains to be seen whether the feds will approve this approach.

Criticism #2: Schools serving lots of poor students were unfairly penalized.

No Child Left Behind used student proficiency to measure schools — and one all-but-inevitable consequence is that school ratings are tightly associated with poverty.

A number of researchers have argued that this approach unfairly penalizes schools for the students they serve and deters teachers from working in those schools. Certain civil rights groups, though, say this method is important in order to maintain high standards and identify schools that need the most help.

Under ESSA, this positive correlation is likely to remain. High-poverty schools will probably still be far more likely to be identified as low-performing, since states, as required by the statute, will continue to use proficiency or overall performance.

Most states also plan to use measures of student growth, which are less tightly associated with poverty. But even when it comes to growth, a number of states are using hybrid approaches that don’t break the link between performance and poverty. Other common indicators, like chronic absenteeism and high school graduation rates, are also tightly related to student income.

A review by the Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank, found that only a handful of states would likely be fair to high-poverty schools. Matthew Di Carlo of the Shanker Institute, a think tank affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers, came to a similar conclusion.

“ESSA perpetuates long-standing measurement problems that were institutionalized under No Child Left Behind,” Di Carlo wrote. “The ongoing failure to distinguish between student and school performance continue to dominate accountability policy to this day.”

Criticism #3: Schools were pushed to focus on kids near the proficiency bar and ignore others.

Another problem many identified under No Child Left Behind was that proficiency created an all-or-nothing definition of academic performance — that is, a school was penalized if a student fell short of the proficiency bar by a single question, yet didn’t get extra credit for those who scored far above proficiency. In other words, schools had less incentive to help kids far above and far below proficiency.

A number of states seem to have taken this to heart. The Fordham Institute report gave eight out of 16 states a strong rating in whether there are incentives to “focus on all students.”

To do that, some state plans emphasize student growth or judge schools based on average overall test scores. Several states plan to use those measures for a majority of their elementary and middle school ratings.

Still, proficiency continues to play a major role in many state plans. Moreover, the use of chronic absenteeism risks replicating the problem: schools will have an incentive to focus on kids just short of the bar to be deemed chronically absent (often 15 days out of school).

That said, there remains significant debate about whether this downside actually exists. Although older research on accountability systems in Chicago and Texas showed that teachers focused more on “bubble kids” — that is, those near proficiency — a study of several states during the NCLB era did not find evidence of this.

Criticism #4: States didn’t do a good job helping low-performing schools improve.

The mission of NCLB — and now ESSA — was to identify schools that need help, incentivize them to improve, and if that doesn’t work, require states to intervene. Perhaps the most troubling legacy of No Child Left Behind, as well as the Obama-era school turnaround program, is what we didn’t learn: what interventions truly improve a struggling school.

States have tried a variety of strategies — including improving support for teachers, adding social services, closure, and conversion to charters — and have found mixed success. (There is some evidence that dismissal of a critical mass of teachers and the principal, combined with hiring flexibility and additional resources, is a promising approach.)

Perhaps because the research is so inconclusive — as well as due to political considerations — many states have been vague about how they plan to intervene in schools in the future.

“Instead of taking the opportunity to design their own school improvement strategies, the state produced plans that are mostly vague and non-specific on how they will support low-performing schools,” according to the review by Bellwether.

One exception, the report notes, is New Mexico, which created a menu of specific options — including closure, charter takeover, or significant restructuring — for schools that are persistent low-performing. This is similar to the federal School Improvement Grant program, which produced inconsistent results.