With its recent adoption of a tax credit scholarship program, Illinois became the 18th state to adopt an innocuously named — but highly controversial — policy that critics have described as a “backdoor voucher.”

In some sense, the description is apt. But by injecting a middle layer into the government’s support of private school tuition, tax credits help avoid some of the legal and political obstacles that have dogged efforts by advocates, like Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, to promote school choice through vouchers.

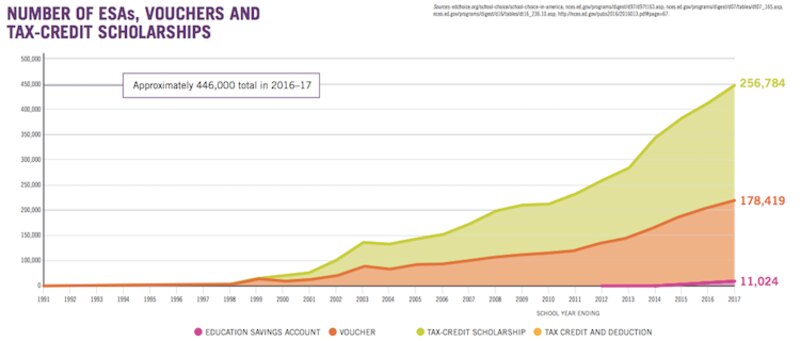

Perhaps as a result, more students now use tax incentive programs than vouchers to attend private schools in the U.S. A federal tax credit is also seen as the Trump administration’s favored approach for promoting school choice at the federal level, though its immediate progress looks increasingly unlikely.

The 20-year history of this approach offers insights into why it has taken hold: resistance to legal challenge; limited government oversight, appealing to among free-market advocates of school choice; and a more politically palatable branding than vouchers.

“This is far better than vouchers — it is easier to pass and easier to uphold,” Trent Franks, a conservative activist and now a U.S. congressman, said in 1999 after Arizona’s state supreme court upheld its tuition tax credit program. “I think this is the direction the country will go in.”

He proved largely right.

Arizona’s pioneering approach

The first tax credit program was passed in Arizona in 1997. Arizona’s constitution, like most other states’, bars public dollars from going to religiously affiliated schools. Proponents knew any plan to promote private school choice would likely end up in court.

So they landed upon an ingenious approach that would make the initiative more likely to survive legal challenge. Instead of issuing vouchers for private school tuition — like Milwaukee had done since 1990 — the state would outsource that role to nonprofits. Those groups would get their money from donations, encouraged by generous tax credits.

It worked like this: An individual could donate up to $500 to a nonprofit, then get a tax cut for the exact amount they donated. The nonprofit would take the donated money and use it to offer tuition stipends — essentially vouchers — to families who met certain conditions. That system allows the state to promote the tuition subsidy, losing $500 in revenue for each maxed out donation, without paying for it directly.

Arizona’s program has since grown, and the state has created a number of other tax credit programs. (This approach is distinct from programs that give individual families tax breaks for educational spending on their own children; Illinois has had such an initiative since 2000, while Minnesota has had one since 1955.)

Arizona’s and Milwaukee’s policies look similar. In both places, students can receive a subsidy to attend a private school, and it comes at the expense of state revenue. But crucially, in Arizona, the government never had the money to begin with.

“The point was in part to ensure that these were not government-run programs,” Lisa Graham Keegan, who was Arizona’s school superintendent when the tax credit program passed, told Chalkbeat. “Those scholarships are completely separate, both for legal reasons and for philosophical reasons.”

Tax credits: the legal survivors

Private school choice across the country have been inundated with legal challenges, but tax credits have proven remarkably resilient.

Although voucher programs have continued to grow and were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2002, they have also faced legal challenges in state courts. Colorado’s top court, for example, struck down a voucher program in 2015. (The case is currently being reconsidered in light of a recent Supreme Court decision.)

But tax credits have never ultimately lost in state or federal court, prevailing in Arizona, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, New Hampshire, and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Tax credits “grew up as a result of saying we need a different vehicle than vouchers in states that have legal issues,” said Robert Enlow, the president of EdChoice, an Indianapolis-based group that backs both vouchers and tax credits. (EdChoice is a funder of Chalkbeat.)

Often, cases have been thrown out before substantive arguments can be made, amounting to a win for the programs: Some courts have ruled that private organizations or individuals do not have legal standing to challenge tax credits, since they aren’t government expenditures.

That was the decision in the 2010 Supreme Court case Arizona Christian School Tuition Organization v. Winn, in which the majority said equating government spending and tax credits was “incorrect.”

“When Arizona taxpayers choose to contribute to [scholarship organizations], they spend their own money, not money the State has collected,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote.

Light regulatory touch proves a blessing and a downside

To Arizona conservatives skeptical of both regulation and the education establishment, the system had an additional benefit.

“The point was in part to ensure that these were not government-run programs,” said Graham Keegan, and additionally that “these don’t become government dollars.”

Nationwide, tax credit scholarship programs appear less regulated than voucher programs, some of which require private school students to take state tests or for schools to undergo financial audits.

Free-market oriented supporters “see ‘neovouchers’ as much less likely to be regulated and have restrictions — the government strings attached — than a traditional voucher law,” said Kevin Welner, a University of Colorado professor who wrote a book on the rise of tax credit programs and is generally critical of them.

A 1998 essay published by the Mackinac Center, a conservative Michigan think tank, made this case explicitly: “Tuition tax credits also create very different effects than vouchers. … Vouchers are more likely to be viewed as a rationale for regulating the entity that receives the subsidy.”

This has played out in practice. One analysis compared several voucher programs to a number of tax credit programs and found that, in almost all cases, vouchers were more regulated. Most tax credit systems had few, if any, financial reporting or disclosure requirements. (Notably, Florida’s program, the largest in the country, was the most regulated tax credit initiative.)

Many tax credit programs do not require participating students to take state exams, and if they do, the tests are rarely comparable to the assessments taken in public school. This means that while voucher programs have been widely studied, there is little research on the effect of receiving a tax credit scholarship.

Supporters of this approach argue that such requirements discourage private schools from participating.

Limited oversight, however, has proven something of a political liability, insofar as it has allowed for financial malfeasance. National media have drawn attention to how one prominent politician and advocate for Arizona’s program was also able to profit personally from it, for example.

“I think [limited regulation] is a feature that has some bugs,” said Enlow of EdChoice. “We need to have transparency. The programs, like Florida, which are very transparent and very open to data collection, I think are very important.” He declined to name any tax credit programs that, in his view, lacked sufficient transparency.

The use of the tax code has also raised another concern: Under some tax credit systems, “donors” can actually earn a profit by taking advantage of both state and federal tax breaks.

Selling tax credits

How exactly to brand tax credit programs has been the subject of fierce debates. Opponents have called them “neovouchers” and “voucher schemes,” while supporters sometimes portray them as entirely distinct from vouchers.

Tax credits tend to poll better than vouchers, and Welner thinks that may be because it’s less clear to most people what they are.

“People’s eyes get bleary and they tune out when people start talking about tax credits,” he said. “That helps to avoid a situation where they respond to it the same way they respond to a voucher proposal.”

Tax credits are essentially a tax cut, which can be a selling point for some, especially conservatives. Advocates sometimes also downplay the costs of tax credits to the government.

“Is it foregone revenue? Sure, but it doesn’t mean it’s the state’s revenue,” said Enlow.

The distinctions between vouchers and tax credits, though, may ultimately matter less to lawmakers in states where they are being debated. In Illinois, critics connected tax credits to vouchers, and Democrats were largely opposed to the tax credit initiative that ultimately passed.

“In my experience the arguments have been the same whether it’s a tax credit bill or a voucher bill when you’re talking with legislators,” Enlow said. “There’s some nuances, but it’s still the same.”

Correction: An earlier version of this piece misstated the name of a free-market Michigan think tank, which is the Mackinac Center.