Students in the country’s largest private school choice program were more likely to attend college than similar students who remained in public school, according to a study released Wednesday. But the Florida program didn’t seem to help many students actually complete a degree.

It’s the latest volley in a long-running debate over the effectiveness of school vouchers and tax credits for private school tuition, policies that U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has championed.

The study may bolster claims that these programs help students in the long run, and shouldn’t be judged only by test scores. In recent years, those short-term results have been middling at best and dreadful at worst.

Critics will likely seize on the fact that Florida’s program had only a small impact on degree attainment, and that the bump in attendance was concentrated in community colleges.

“An increase in college enrollment, even if it’s in the community college sector — in part because that’s where most kids in Florida, especially from low-income families, go to college — I do view it as a positive finding for the program,” said Matthew Chingos, who conducted the research with Daniel Kuehn, both of the Urban Institute, a D.C.-based think tank.

“Do we have to temper that with a little bit of caution given the attainment result? Sure.”

Attending private school with a voucher may increase college attendance, but not completion

The paper focuses on the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, which was enacted in 2001 and now serves nearly 100,000 students. The program encourages donations to nonprofits that issue vouchers to low-income families to pay for private school.

(The study was funded by a number of organizations that support school vouchers, including the Walton Family Foundation, the Oberndorf Foundation, and the Foundation for Excellence in Education. The Walton Foundation is also a funder of Chalkbeat.)

Chingos and Kuehn looked at 10,000 students who used a tax credit to transfer out of a public school between 2004 and 2010. They then compared them to students with similar test scores at the same public school who didn’t use a credit to leave the school.

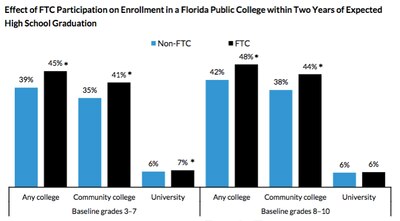

The paper estimates that participating in the tax credit program raised enrollment in Florida public colleges by about 6 percentage points, with virtually of all of the increase coming from community colleges. Students who used the tax credit in an earlier grade were half a percentage point more likely to enroll in a public four-year college.

But the program had little effect on whether students received an associate’s or a bachelor’s degree, though using a tax credit in earlier grades may have slightly increased a student’s chance of earning a two-year degree.

The authors note that only a small number of students had been out of school long enough to complete a four-year degree.

Most of the students studied only used the tax credit for one or two years, though those who stayed longer were more likely to enroll in and complete college. It’s not clear whether that’s because the benefits of the program accumulated over time, or because kids for whom the program was working stayed in it longer, or because those who continued to use the tax credit were simply more likely to attend college to begin with.

Researchers say study has limits, highlights larger debate on how to evaluate voucher programs

The key limit of the study is the difficulty in ensuring that the kids who take a scholarship are similar to those who do not.

Doug Harris, a Tulane economist who reviewed the study at Chalkbeat’s request, said it had both strengths — its focus on long-term outcomes — and limitations.

“Two students who have the same measureable characteristics … but make different schooling choices, are clearly different in unmeasurable ways that the analysis cannot address,” said Harris, pointing out that this might make the program look better than it really is.

Chingos agreed that this is a limitation, but said it could affect the results in either direction.

Another concern is that the long-run data is limited to public colleges and universities in Florida. If private high schools are more likely to get kids to enroll in private or out-of-state colleges, that might affect the results, and Chingos notes that data shows this appears to be true at the national level.

Meanwhile, the study highlights the complications in evaluating education programs.

Short-run test score measures are more available but widely seen as limited; long-run outcomes may be preferable but they are more difficult to obtain, and, by their nature, can only be used for established programs. School voucher programs have generally looked better when examining longer-term metrics.

But Florida’s tax credit program seems to have a comparable effect — none or a small positive one — on test scores and long-term measures.

“Both outcomes seem to suggest the same general pattern,” said Harris.

The jury is still out on whether voucher programs that lead to declines in test scores are likely to benefit students in the long run. A recent study found that charter schools in Texas with low test scores also tended to hurt four-year college attendance rates and adult income.