A school district leader with money for teacher bonuses faces a choice: Should she spread the money around to all teachers equally or give more to teachers who have performed best?

A new study, released by the federal government, suggests that merit-based bonuses are the way to go, as they help raise student test scores without making a significant dent in teacher morale. It offers the latest evidence that programs of this sort can help schools and students, despite the common perception that they are ineffective.

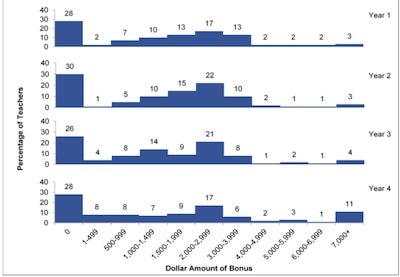

The research focuses on a federal program known as the Teacher Incentive Fund, and compares schools that gave all teachers an automatic 1 percent bonus to those schools that gave bonuses based on classroom observations and student test scores. About 130 schools across 10 districts were randomly assigned to one of the groups.

The result? The schools that gave performance bonuses boosted student test scores throughout the four years of the study, between 2011 and 2015.

The differences between the two groups of schools weren’t big, and they were only sometimes statistically significant. For instance, in year three of the study, performance pay increased student test score performance by 2 percentile points.

But because the program was relatively cheap to implement, performance bonuses were very cost effective. They offered a better bang for the buck than class-size reductions, the researchers estimated.

And what about fears that performance pay would dampen teacher morale or reduce collaboration as teachers competed with each other for a fixed pool of bonus money? There was little evidence of that. According to teacher surveys, the program had only a limited impact on their job satisfaction, interactions with colleagues, or school morale. In the initial year of performance pay, there seemed to be small dips in morale and collaboration, but in year three the effects were actually positive.

The program also led to small increases in teacher retention, which may help explain the positive findings.

The study comes with an important caveat: It relies on test scores alone as a measure of learning. If the incentives pushed teachers to raise scores by less desirable means, like cheating or “teaching to the test,” that wouldn’t say much about the success of the policy.

The research adds to the hotly contested debate about how teachers should be paid. High-profile research in New York City and Tennessee from several years ago found disappointing results for merit pay, solidifying a conventional wisdom that the approach doesn’t work for teachers. Other districts, like Denver, have struggled with the design of a performance pay program and have seen inconsistent results.

But some recent studies have re-opened this debate. An overview of research last year showed that performance pay leads to small boosts in test scores, and a number of studies have found that added pay can help keep more effective teachers in the classroom.

It’s not entirely clear why the studies have reached such different conclusions. But performance-pay programs that judge teachers by test scores alone and only measure short-term effects tend to be disappointing. Programs like the Teacher Incentive Fund and those in Minnesota and Washington, DC, which use performance pay as part of a broader system for evaluating teachers, often produce more positive results.

That doesn’t mean that districts will heed the latest research. In fact, even in the new federal study — which found benefits for students — less than half the districts said they planned to continue offering performance bonuses after the Department of Education grant ran out.