It’s common for high school students to head to college campuses for classes. It’s much rarer for a college to set up shop on a high school campus.

But that is what’s happening at a KIPP high school in New Orleans this year. Bard College, a New York-based private liberal arts college, is enrolling half of KIPP Renaissance’s juniors in a two-year program designed to end with them earning both a high school diploma and an associate’s degree.

It’s a new tactic in the national charter network’s push to get its students to and through college: combining the start of college with high school in a way that makes higher education feel attainable — even unavoidable.

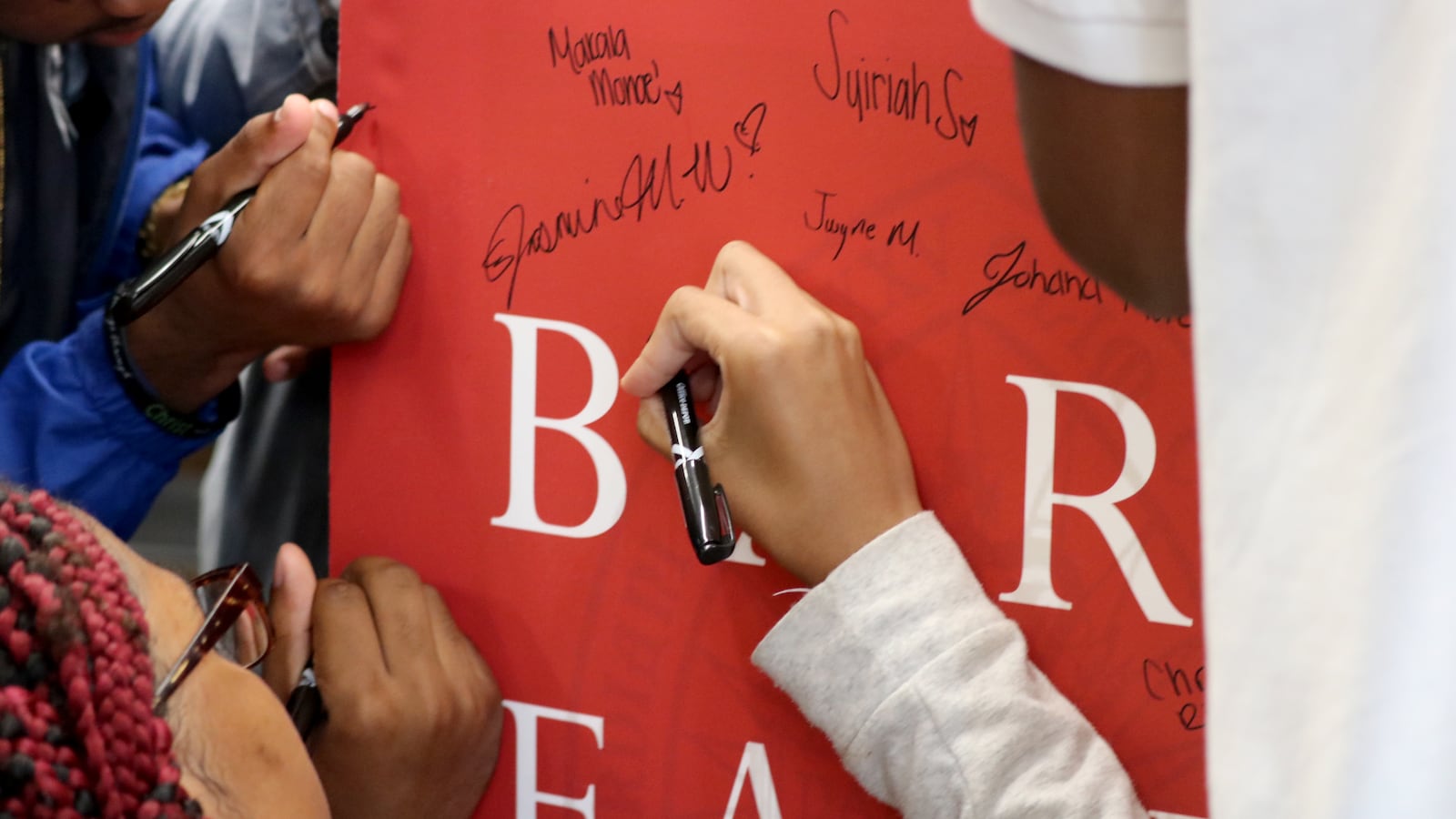

“This partnership helps us not just kind of guess what it would take getting kids to get into college,” said Towana Pierre-Floyd, the principal at KIPP Renaissance, which held a ceremony Tuesday for students entering the program. “Working with Bard [helps us] see how it actually would shake out for students when they start taking college courses full-time and have to navigate time management and rigor in different ways.”

Early college programs, which can cut down on the time and money needed to earn a degree and expose students to the style and pace of college work, are growing in popularity as an option to help students from low-income families and communities of color.

Most of those programs, though, have students earn credits at community colleges during part of the school day. The KIPP-Bard partnership is unique because it’s full-time, housed completely on a high school campus, and operating in conjunction with a charter school. (Bard operates several of its own early-college high schools across the country, but none inside other schools.)

KIPP’s program will work by enrolling students who have completed the majority of their Louisiana high school requirements at the end of sophomore year, school officials said. (The other half of KIPP’s students will follow a different academic program.) Ten Bard staffers, including six professors — some from Bard, others hired locally — will teach courses on KIPP’s campus.

“Bard is not hurting for applicants,” said Stephen Tremaine, the college’s vice president of early colleges. “For Bard, the upside is that the way that higher education in America identifies and searches for talent is incredibly criminally limited to one kind of student that’s one age and often in one neighborhood. We think that colleges miss out on real talent by not being willing to open that up.”

Douglas Lauen, a public policy professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who co-authored a study examining early college high schools, estimates about 300 early college campuses dot the country, with 80 alone in North Carolina. He says the model gained steam in the state after an injection of money from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, supplemented by public funding. (The Gates Foundation is also a supporter of Chalkbeat.)

A small but growing base of research has found the model generally helps students from low-income families — increasing high school graduation rates, boosting associates degree completion rates, and raising four-year-college enrollment, one study out of North Carolina found, though that college enrollment increase was at less selective schools.

“There appears to be a causal effect” of the program on a student’s chances of making it to and through college, said Lauen.

Adding college classes to high school is still a tricky proposition. Some have raised questions about the value of the associate’s degree students leave with and about whether the the courses students take in early-college programs are truly at a college level.

“We have to be thinking, are we giving them a credential for the sake of it, or are we giving them something useful for the job market eventually?” said Nathan Barrett, Lauen’s co-author. Barrett is now an associate director at the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University, about seven miles from KIPP Renaissance.

Still, Barrett and Lauen see real benefits. An associate’s degree can keep students on the path to a higher-level degree, helping them avoid the cost of some college credits. KIPP officials also said they hope the program gives students the confidence to apply to more selective universities than they otherwise would.

“KIPP arguably may have more structure than students will get when they go to college, so perhaps this will get them in a place where they will be pretty much ready to go in the world and persist in college and with a career,” Barrett said.